DIP SETS UP FOMC FOR NOT-QE

EDU DDA Dec. 9, 2025

Summary: All of our “favorite” topics erupting all on the same day, the one which just happens to be right before the Federal Reserve’s December decision. After going through everything, it again becomes clear whatever the FOMC decides tomorrow matters very little, if nothing at all. What does? More trouble with First Brands, an eye-popping development with its DIP. Term repo rates have already soared and there’s still two weeks before the real year-end starts. Finally, JOLTS showed up for both September and October. Job openings jumped but everything else was recession-level ugly.

THAT WAS BEFORE, AND NOW THE DIP IS RUNNING FOR THE HILLS

Only a few hours before beginning to write this, news broke that First Brands is about to come back roaring to the internet version of the front pages. Its DIP loan (which I’ll explain) is being sold by seemingly everyone who holds the notes, shoving its price down unusually to around 60 cents on the dollar. Big trouble even in bankruptcy.

Not coincidentally, that fits with one topic I was already going to bring up given tomorrow’s FOMC. Repo hasn’t gone away, if anything it is heating up again all its own (maybe not) with term rates soaring with two weeks still remaining until the end of year scramble should really begin.

Will this mess be sufficient to add a not-QE QE to the Fed’s Wednesday voting agenda?

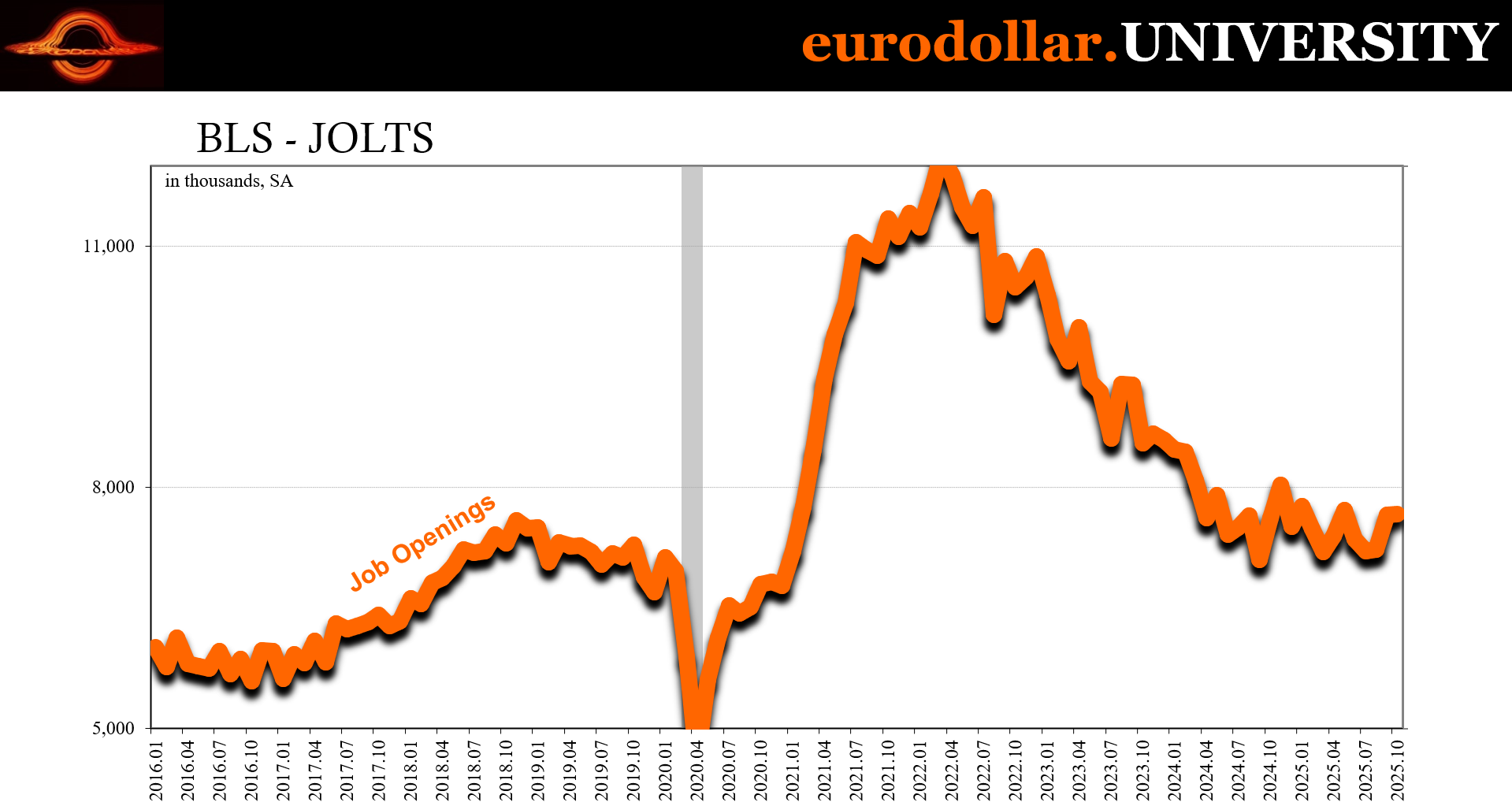

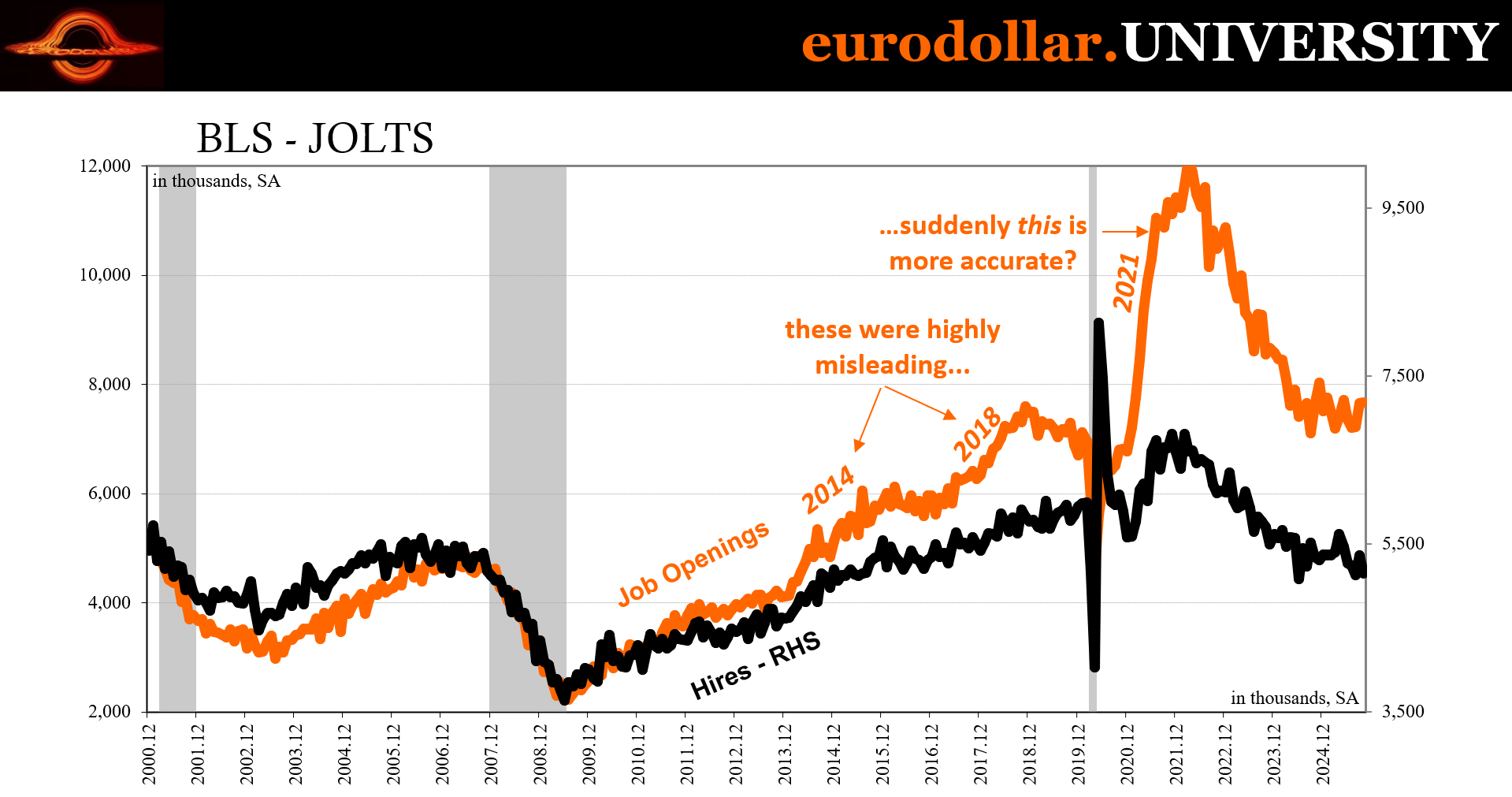

In the macroeconomy, the BLS surprised us (or maybe just me) with both a September and October update to JOLTS. That means finally one for Beveridge. However, that will be misleading again since Job Openings did what they always do – to explain that I’ll look back on one key historical example from a decade ago demonstrating how even the Federal Reserve knew it was an unreliable outlier all the way back then.

Yet, this single data series continues to be the sole one cited by the media solely due to the media’s impression the FOMC takes it seriously. Only when convenient.

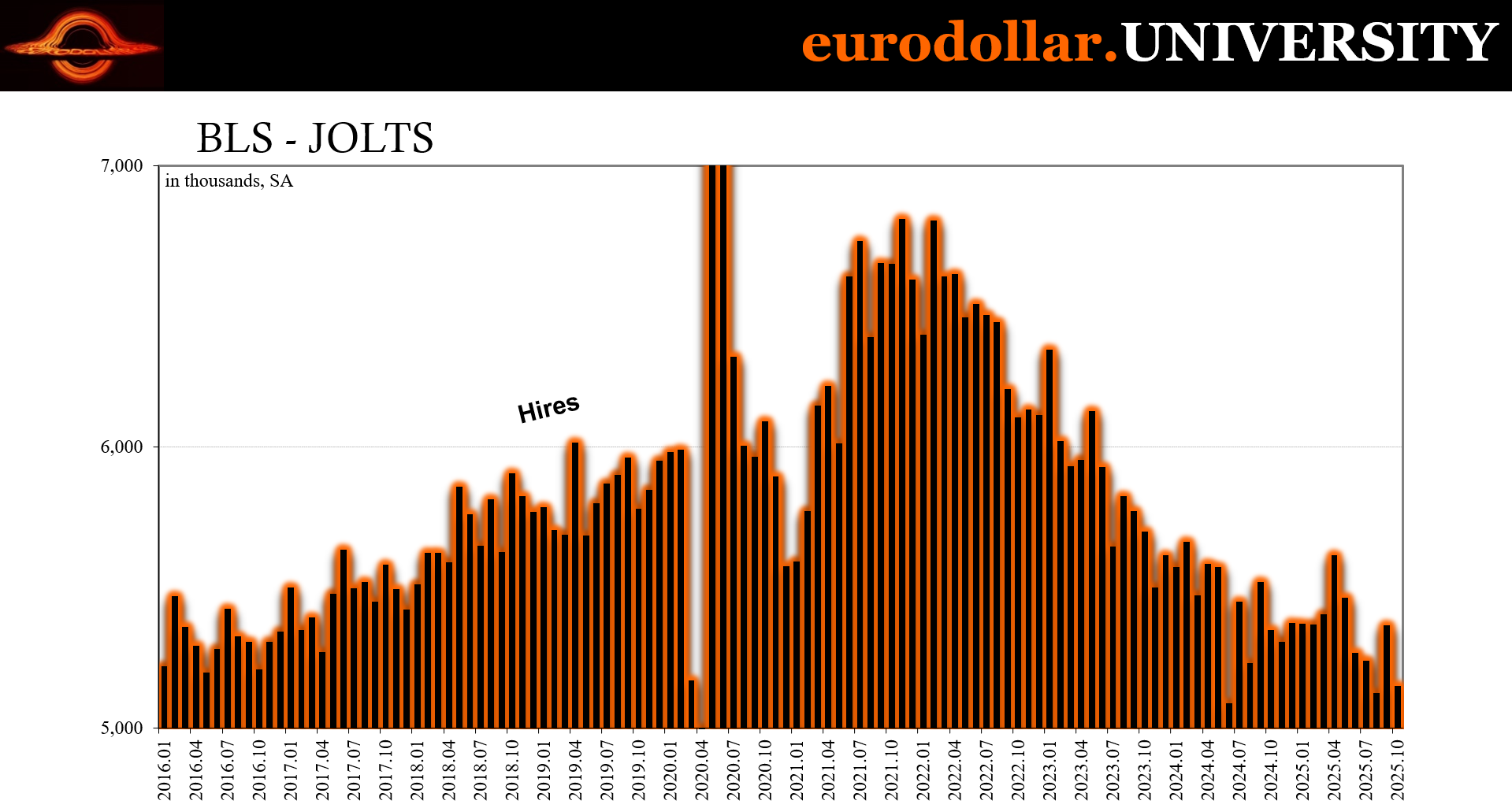

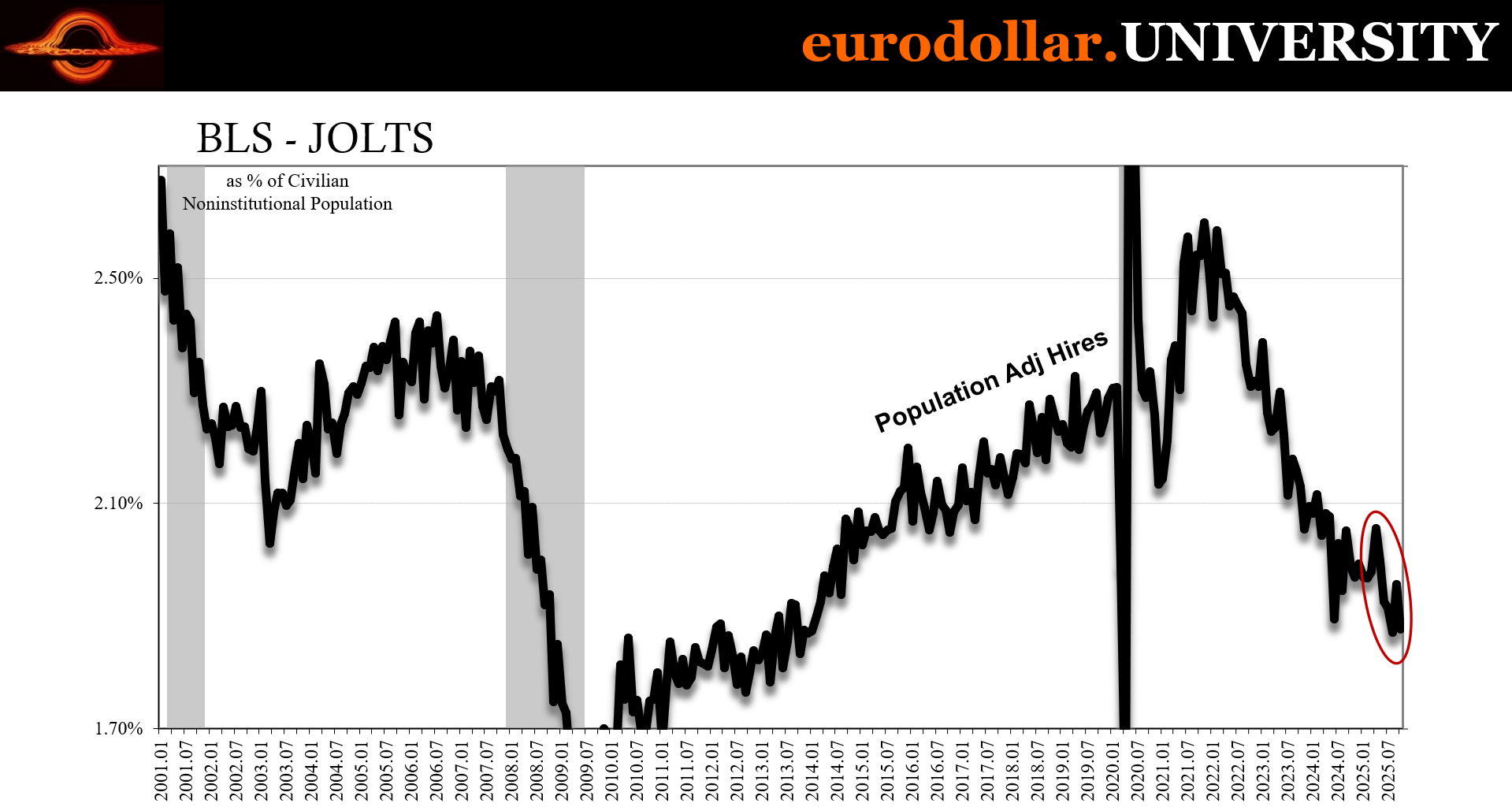

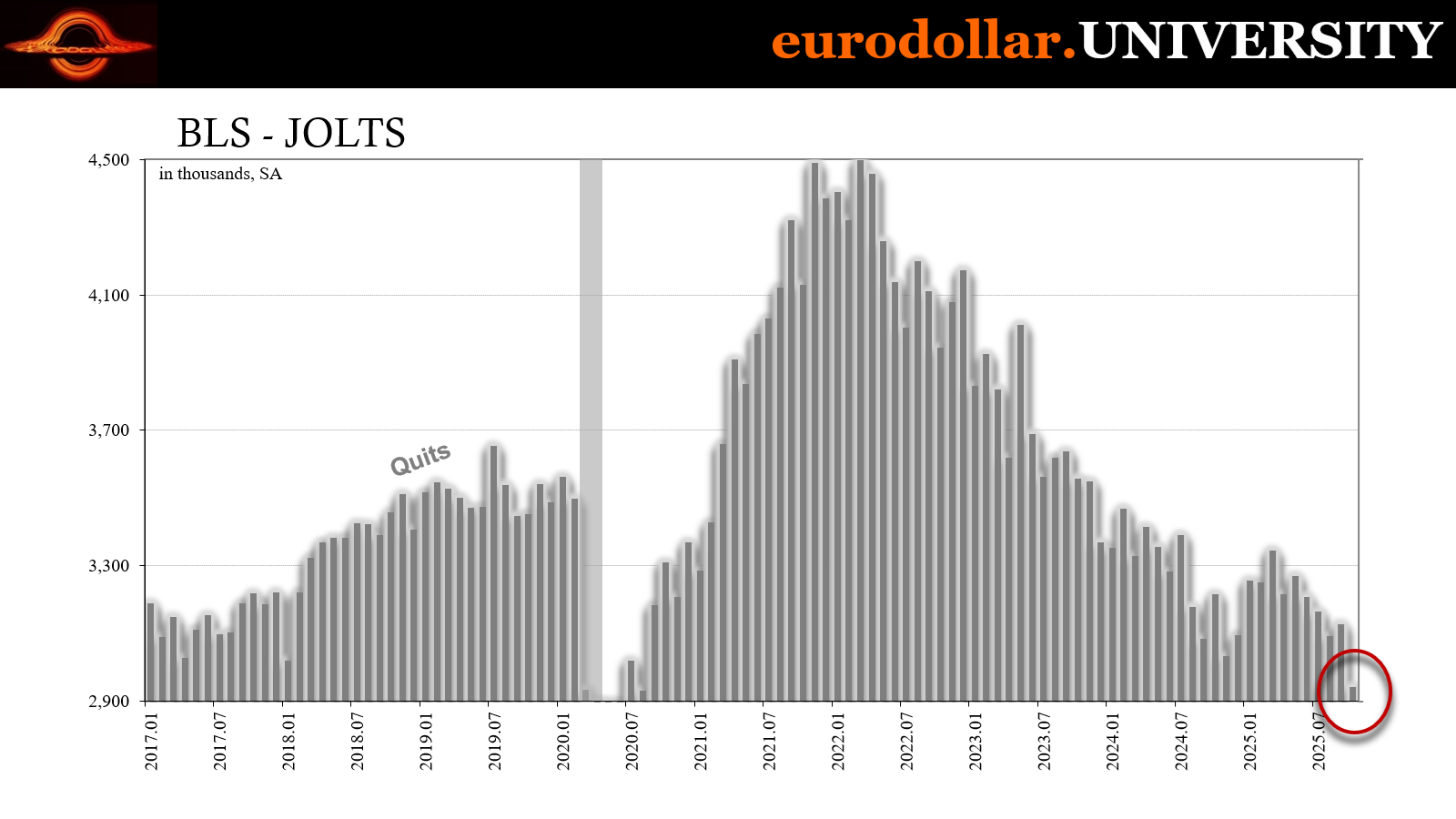

The rest of the series, on the other hand, all showed significant deterioration, severely undercutting Job Openings as just the start. Quits, in particular, plunged while hiring revisited August’s disgust all as the layoff figures are entering the flat Beveridge discussion, too.

While these topics may seem unrelated to those outside Eurodollar University, we know only too well that the latter developments (labor) are key in explaining attitudes playing out in the former (repo and general monetary tightening).

Debtor-in-possession

DIP, or debtor-in-possession, is when a bankrupt company has a trustee appointed to run the bankrupt estate, usually an ongoing company. The trustee has the authority to maintain the business as best as possible, including dispersing funds to vendors, employees, etc., all under the supervision of the judge overseeing the case.

Debtor-in-possession financing, therefore, is essential to make this work and keep the insolvent firm up and running. Lenders come in and provide fresh funds which have to be approved by the court and they get relatively healthy returns for doing so. As a measure of protection, DIP financers are moved to first in line for repayment, called “priming.”

This is to make sure the new lenders are most likely to get repaid out of whatever might be left from the bankrupt enterprise, including jumping over any other senior creditors. This isn’t without their knowledge, as the bankruptcy process tries to be sensitive to all creditor classes balanced against the needs to keep the company’s doors open, therefore the requirements on the trustee.

It is highly unusual for DPI financers to panic-sell their claims at all let alone this soon in the bankruptcy process. As you might already suspect, something like that would only happen if some of those lenders start to believe there isn’t anything left to protect their claims.

This appears to be what just happened for First Brands. Here are the relevant parts of Bloomberg’s late afternoon summation:

Major investors in First Brands Group have offloaded stakes in the bankrupt auto supplier’s debt in recent days, causing the value of its most senior loan to collapse and prompting it to pull forward a lender call to calm nerves.

Marathon Asset Management and Redwood Capital Management are among funds who have sold chunks of the super-senior loan they provided First Brands as it crashed into a Chapter 11 restructuring, according to people familiar with the matter.

Diameter Capital Partners, Monarch Alternative Capital and UBS Asset Management have sought to sell portions of their debt stakes but it’s unclear if they were successful, said the people, who asked not to be named because the information isn’t public.

It’s rare for investors to head for the exits so soon after a bankruptcy filing, and some recent trades suggest concern about the ability to turn around First Brands’ business as it contends with revelations of billions in missing cash and of alleged fraud by its founder.

According to these same reports, First Brands’ DIP loans were trading at just 63 cents on the dollar! That’s just wild for a case that’s barely a month old.

While certainly an interesting story all its own, the potential systemic ramifications are the same as they have been, only further heightened by these developments. First, the business of First Brands, meaning auto supply therefore cars, trucks and vehicles writ large. To sell out of DIP means there isn’t much faith among the superlenders for the company to keep it going.

What does that say about the state of the car industry and most of all consumers who otherwise would DIY their vehicles? More confirmation of the same thing we got from IP’s drastic revisions, specifically on production of consumer goods.

Selling of First Brands DIP could be, however, just too much fraud being uncovered, but more likely they aren’t seeing the kinds of business prospects which might be necessary to overcome whatever nefariousness the previous owner had gotten up to.

Beyond those immediate concerns, this is just another bad sign at to the lack of due diligence which appears to have been endemic at least in factor financing if not more broadly across shadow banking as an industry. And then, to have the DIP lenders come in only to turn around flee this early in the process, it does not speak highly of anything.

Red flags galore.

Early year-end to end not-QE QE reluctance

The timing for First Brands’ latest drama could not have been worse, either. We are heading toward year-end which already means window dressing and funding tightness even in the most benign years. Last year wasn’t quite that, seeing some significant stress.

While the Fed is focused on bank reserves and the previous rushed end of QT, therefore so is the mainstream media, the repo market itself has eyes on more problems like these being revealed in less-than-ideal ways through these frauds and bankruptcies. More reasons to be skeptical and take more care and caution over potential exposures.

Those with cash might want to hold a little extra on balance sheets just in case. Collateral might not get swapped with the same vigor it might have earlier in the year. Tightness all around.

There were no serious repo borrowings at the Fed’s window today. SOFR, meanwhile, continues to be elevated anyway, still at 3.95% as of yesterday’s FRBNY calculation, just five basis points below the fed funds upper bound.

Where we do see concerns right now is in term repo – that is ST borrowing which is longer than overnight. Borrowers are beginning to (rush) put together collateralized financing to tide them over at the end of the year and, so far, it is already getting uncomfortable. The GC rate for December 31 and January 2 was a whopping 4.25%.

Assuming the Fed cuts by 25 bps tomorrow, which the market expects, that’s an enormous 60-bps spread above just IOR, 50 bps above what should be the fed funds upper bound by then. That’s a lot of borrowers competing for limited financing and it’s only December 9. The real squeeze typically shows up just before Christmas, so the market is still roughly two weeks before that point, too.

Will that be enough for the Fed to launch a not-QE QE? No one can say for sure, but officials are not going to want watch the repo mess get out of control and dominate headlines entering 2026. They may, however, be content to encourage repo facility use or even Primary Credit as a psychological tactic if completely reversing their balance sheet rundown is too much for the divided committee to take up.

Should the FOMC opt for a not-QE QE, that would be a sign policymakers see the growing repo problem as significant enough to warrant a second response (the first being early end to QT); which is also the counterargument to doing it, not wanting to confirm this is something, enough which concerns the central bankers to the point they are doing something about it.

Honestly, there is really no way to predict how the bureaucrats will react. Then again, we only need wait until tomorrow afternoon for an answer.

Some background: in order to create more bank reserves, the Fed has to buy some kind of financial asset from Primary Dealers. The thought was by adding more reserves bank in permanent fashion, it would raise the cushion of available liquidity to answer all ST borrowing needs. In 2019, Powell’s group decided they would exclusively target Treasury bills for the sole reason of claiming it wasn’t QE – as if buying Treasury notes and bonds was somehow categorically different.

As Powell himself implied, the Fed’s intent was what mattered. Not-QE QE was a fine-tuning operation supposedly to aid ST money markets whereas bond buying like in earlier instances was meant to “stimulate” the economy more broadly, not that any of them did. Nor did liquidity improve regardless of the level of bank reserves, either, so there’s that, too.

Jobbing Beveridge

Surprising maybe only to me, the BLS released JOLTS for both September and October today. I confess to not having looked at the schedule all that closely, so I was only expecting the one month. The government probably should have left it that way given the October estimates were downright ugly.

Surprise, surprise, not Job Openings (JO), of course. For JO, those rebounded sharply by almost half a million in September then remained largely unchanged around that same level for October. As per usual, the mainstream media picked right up on this proclaiming the labor market on the mend, adding more fuel to KC Jeff among other claimed implications.

Never mind how this same scenario has happened in JO several times over the past few years, each and every time the media falling for it when it means absolutely nothing, the labor market constantly weakening anyway. As we’ll see, JO is completely, utterly unreliable and has been for many years, from back when the level of overstating labor demand was far less than it is today.

Since JO goes on the Beveridge curve, the latest update for it is still on the flat part if somewhat less than it had been during the summer.

However, every other datapoint in JOLTS undercuts the series, totally contradicting the idea the labor market steadied let alone rebounded somehow. Start with hiring. We last left it in the depths of a cycle low (hiring rate) for August, an ominously weak result which only fit too well with weak demand for workers (regardless of JO) consistent with some degree of job shedding.

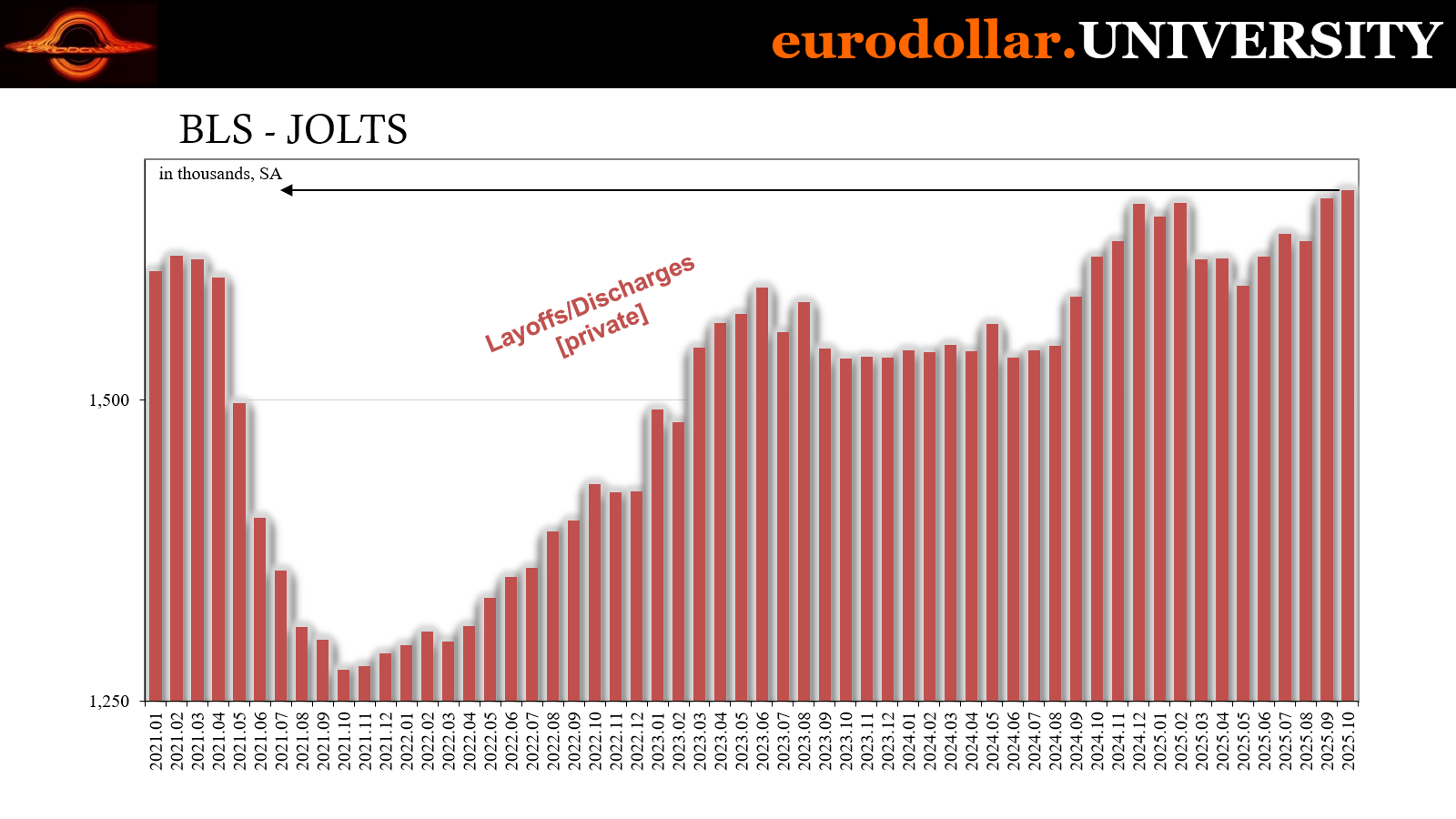

The latest updates put hiring as slightly higher in September before sinking right back to those August depths in October. While some will be quick to blame the government shutdown, JOLTS estimates don’t show it being a substantial factor. Instead, the weakness was concentrated in the private economy, corroborating ADP which only measures private payrolls.

Even more astonishing than JOLTS hires, quits collapsed for October. Like hiring, quitting was slightly higher than August in September but then during October plunged below 3 million for the first time since 2020! The same month when job openings were allegedly somewhat more plentiful, American workers just didn’t see it that way, holding on to their current jobs like they would in outright recession.

Together with hiring, there is no way JO is anything but flawed and highly misleading - again. Employers were supposedly placing ads for employees but not hiring many because workers were so happy with where they work currently? Not a chance. Workers know there is no one hiring and they are better off hunkering down and seeing how this goes over the coming months.

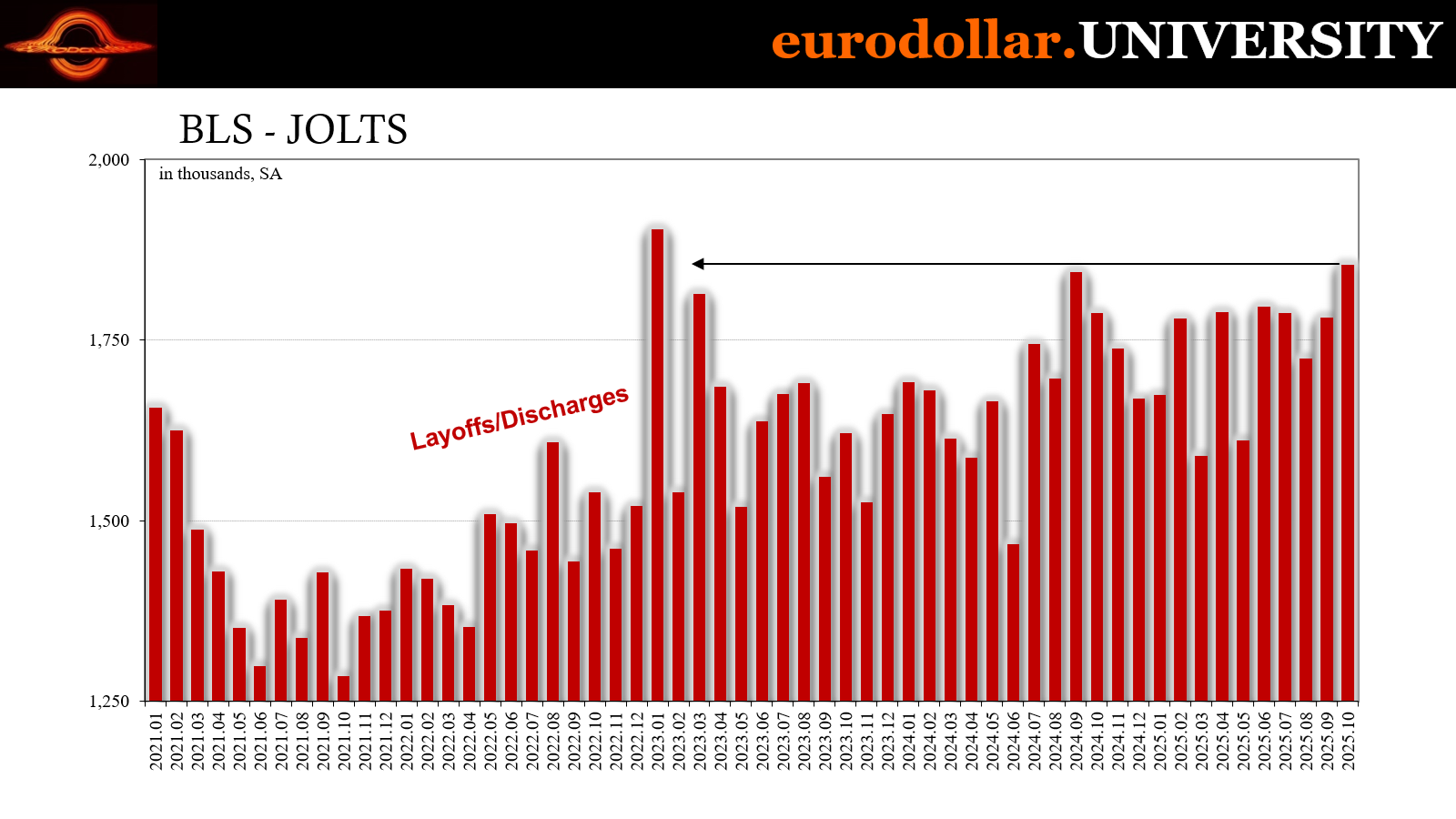

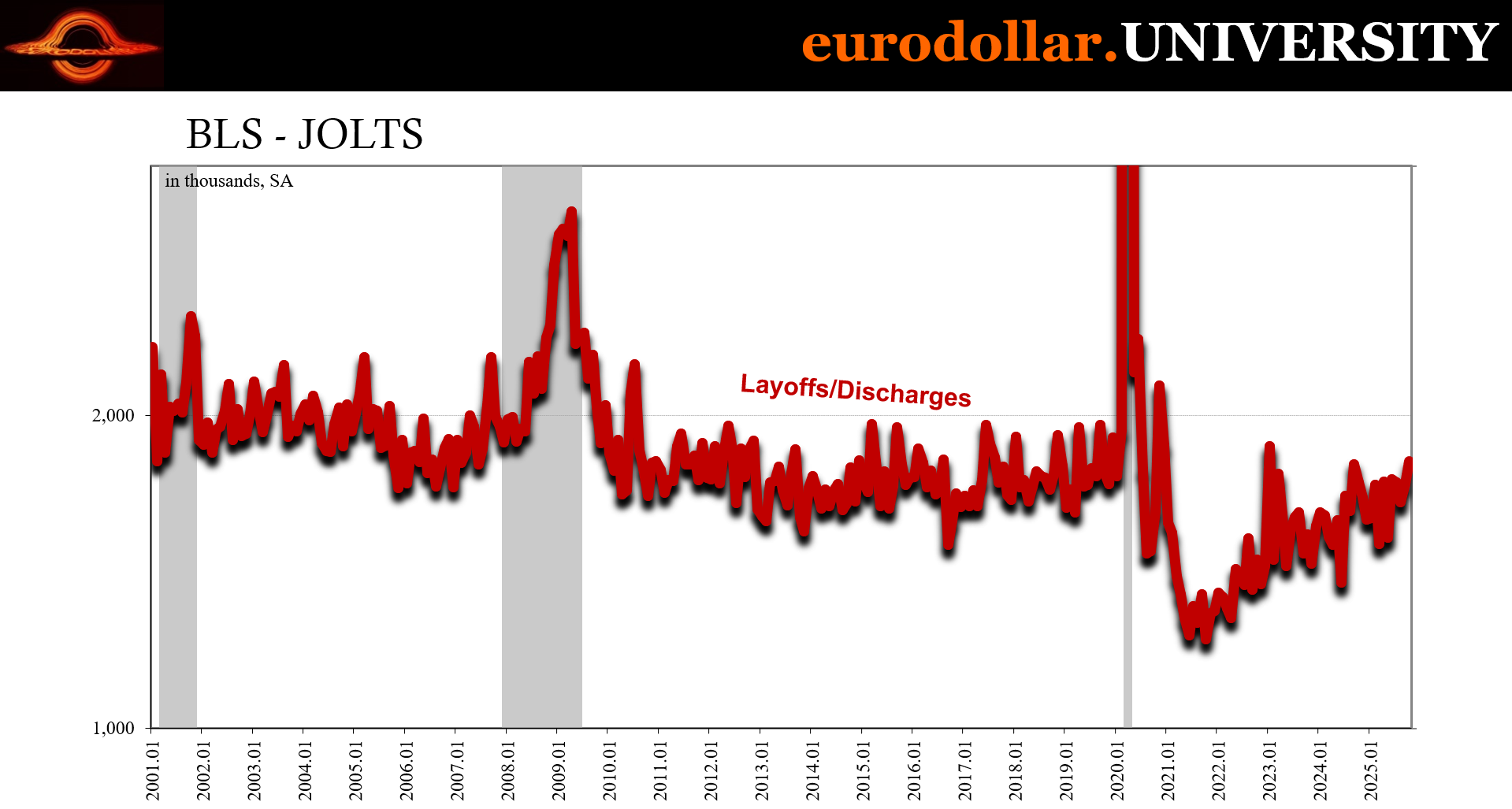

And if all that wasn’t enough, JOLTS also found more layoffs, too, coming up with the biggest total since the start of 2023. For just private job cuts, it was the most dating to 2020.

Higher layoffs, worrisome levels of quitting, and recession hiring. But job openings are a sign of stability, maybe even a pickup? Not a chance.

We’ve seen this before (again)

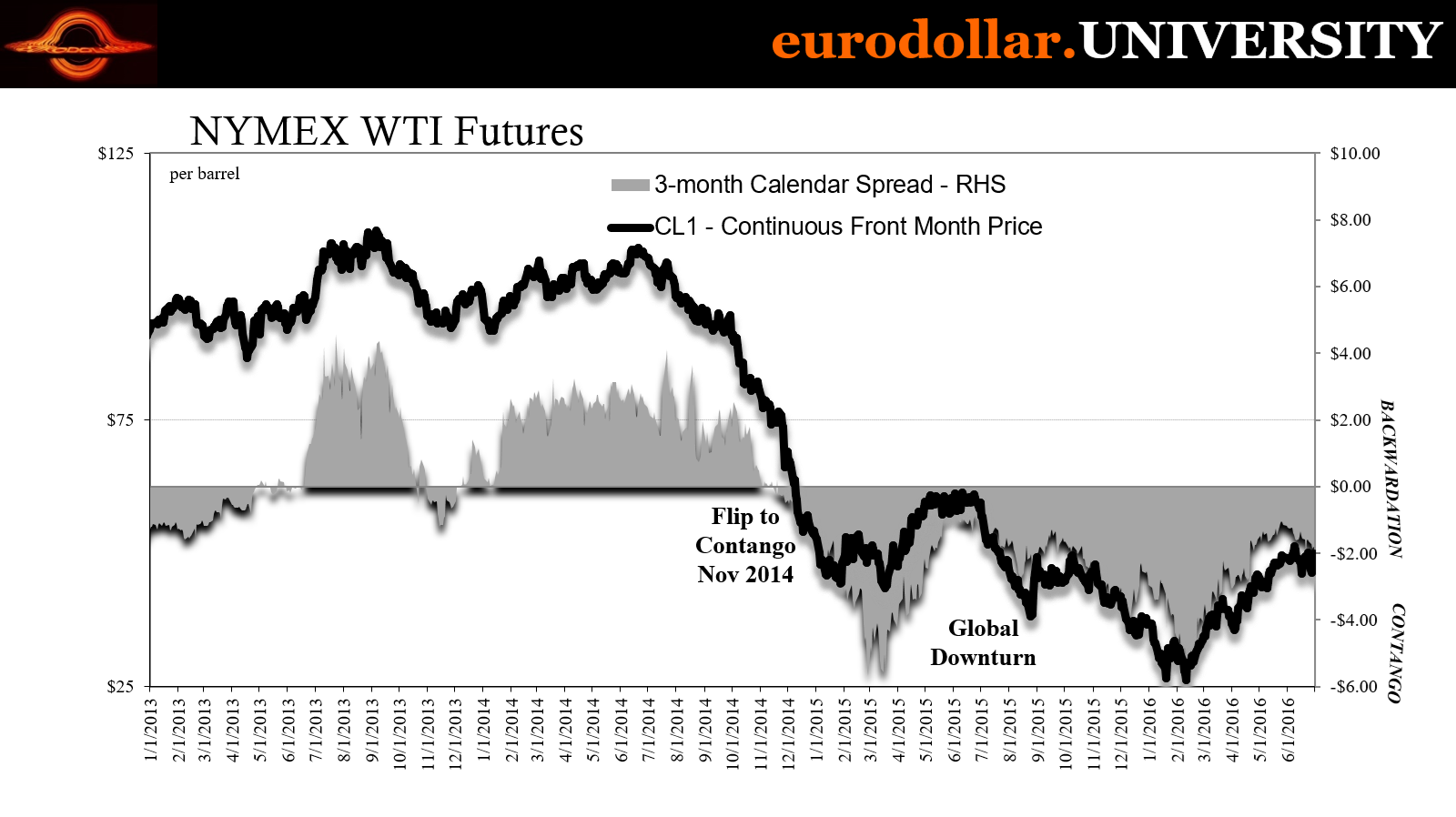

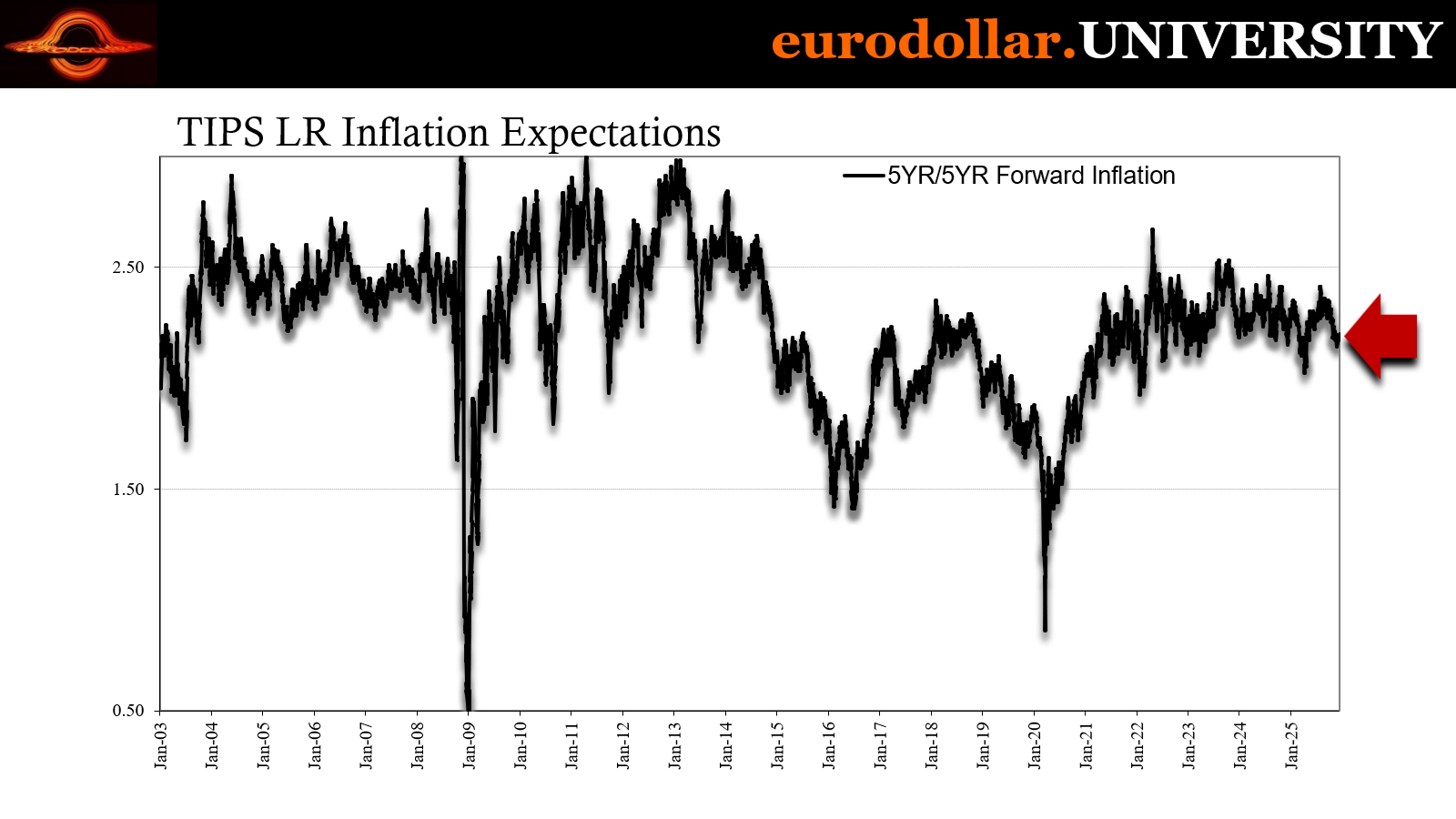

As you might imagine, inflation was the hot topic of conversation during the December 2014 FOMC meeting. For these central bankers, it was surely the launch point for the long-awaited recovery – even though by every major market-based reading it would prove to be the end of that very thing. The “best jobs market in decades” had brought the unemployment rate down quickly, QE was being terminated, and rate hikes on the agenda for the first time (seriously) since 2006.

As a consequence, the term “inflation expectations” was used 97 times during the discussions.

Already there was a problem, however. There is always a problem. In December 2014 you might remember what that was in this context. While committee members like Richard Fisher from Dallas spoke of Saudi Aramco and the Texas oil free-for-all, the “supply glut” theory would keep coming up short of explaining fully what was going on with crashing oil prices.

It was all temporary, they said. While the supply was brand new for these central bankers it should’ve been preposterous to assume it was also unforeseen by futures markets. But that would’ve required looking at the unfolding oil price crash in another way, like the related surging dollar.

Those like then-San Francisco branch President John Williams (since promoted, of course, to lead the New York branch), the Fed’s main R* guy, he refused to believe his own lying eyes.

MR. WILLIAMS. This outlook for gradually rising inflation is supported by the continuation of well-anchored inflation expectations. I agree with President Fisher, I believe inflation expectations have remained well anchored.

Both near term and long run market-based inflation expectations had already begun their plunge along with WTI. Setting those aside, as Fed bureaucrats always do, Williams pointed to survey-based measures of the same. Markets were imperfect thus household surveys superior, he concluded, because there might be some Singapore financial groups buying TIPS off the back of Middle Eastern speculators splicing growing contango profits.

Or something.

MR. WILLIAMS. I am unconvinced that market prices likely reflect the preferences of American households in the way that the memo lays out. One reason is that a large share of American households doesn’t actively participate in financial markets. Indeed, the marginal investor could well be a foreign hedge fund, which would invalidate the welfare rationale for using market prices.

Ultimately, of course, it didn’t matter. Within months it became clear survey-based readings on intermediate and long run inflation expectations had already joined the markets in saying John Williams was all wrong.

He and the rest of the FOMC were fooling themselves – and, as always, you really have to read these transcripts to truly appreciate the pure mental gymnastics, the lengths to which these people will go to deny what’s happening right in front of them. Truly remarkable, as we’re seeing again here in 2025.

Internally, there wasn’t nearly as much rousing confidence as had always been projected outwardly. Some voting members of the committee and some members of the various staffs were getting concerned that something was up with downward inflation. That meant trouble in terms of the recovery and economic potential. The big picture.

What had triggered Mr. Williams’ diatribe and had sent him off taking up literally pages of transcript was a couple of included memos (he referenced only one in the quote above) presented to the FOMC on the topic of…inflation expectations. A Minneapolis branch staff paper on the subject published in August 2014 had already concluded that it might be a mistake to write off the market-based inflation outlook.

That paper proved correct.

A second one from the Fed’s Division of Research and Statistics published only a week or so before this meeting, made available to us only six years later, was more conventional. The kind of context we’ve been discussing here, the possible macro slack and any tightening in the labor market.

Why wasn’t inflation like the unemployment rate?

And remember, this was December 2014. From the memo:

In particular, the JOLTS job openings rate suggests a much tighter labor market than does the unemployment rate gap. In contrast, the unusually wide labor force participation rate gap and elevated share of involuntary part-time work—margins of underutilization that are not captured by the unemployment rate gap—suggest that the unemployment rate gap somewhat understates the true degree of slack the in labor [sic] market at present.

From this perspective, it’s pretty simple stuff. All the TIPS market said was that the more time passed and inflation (particularly wages) didn’t break out the more likely the unemployment rate was faulty (and by extension Fed QE and ZIRP policy). It was hard to conclude anything other than how the official unemployment rate was misrepresenting the macro slack that was present in December 2014 for the reasons cited in the memo. JOLTS Job Openings was the outlier among several other indications siding against the unemployment rate.

Janet Yellen never told you that part.

And with oil prices crashing, that pissed off John Williams something awful. He could see what that would mean, at least one more year where the inflation numbers would significantly underperform, ruthlessly denying him of the victory lap he and the rest of those like him were so desperate to take. He was sick of all that; it had already been five years, four QE’s, and a Twist.

Williams was in a rush to declare success. The oil market would digest the transitory supply glut, he declared, and not so long afterward by 2016 the inflation numbers would confirm his predetermined viewpoint. The market, looking at it differently, was standing in his way. Job openings were not, in fact, accurate. And that was a decade ago when the series was far less obviously egregious than it is right now.

Our “favorite” topics all wrapped together not quite in one package but making the most noise together one day before the FOMC. Repo and cockroaches on the one side, with the latter far better explaining what’s already building in the former. Meanwhile, behind everything, flat Beveridge; the worse the labor market gets, the more troubling the economy will be to credit portfolios and maybe more.

And in the case of September and October BLS, we have the weird though not unheard-of condition where flat Beveridge is overwhelmingly displayed in all the JOLTS data except the one which plots directly on the Dr’s curve!

Job openings remain an outlier, but of course that’s the one the media and mainstream will turn to. Probably KC Jeff, too. As far as not-QE QE, that’s a toss-up.

Then again, as I’ve been saying and today’s roundup shows, the December FOMC doesn’t really matter.