SUDDENLY VERY INTERESTING

EDU DDA Aug. 15, 2025

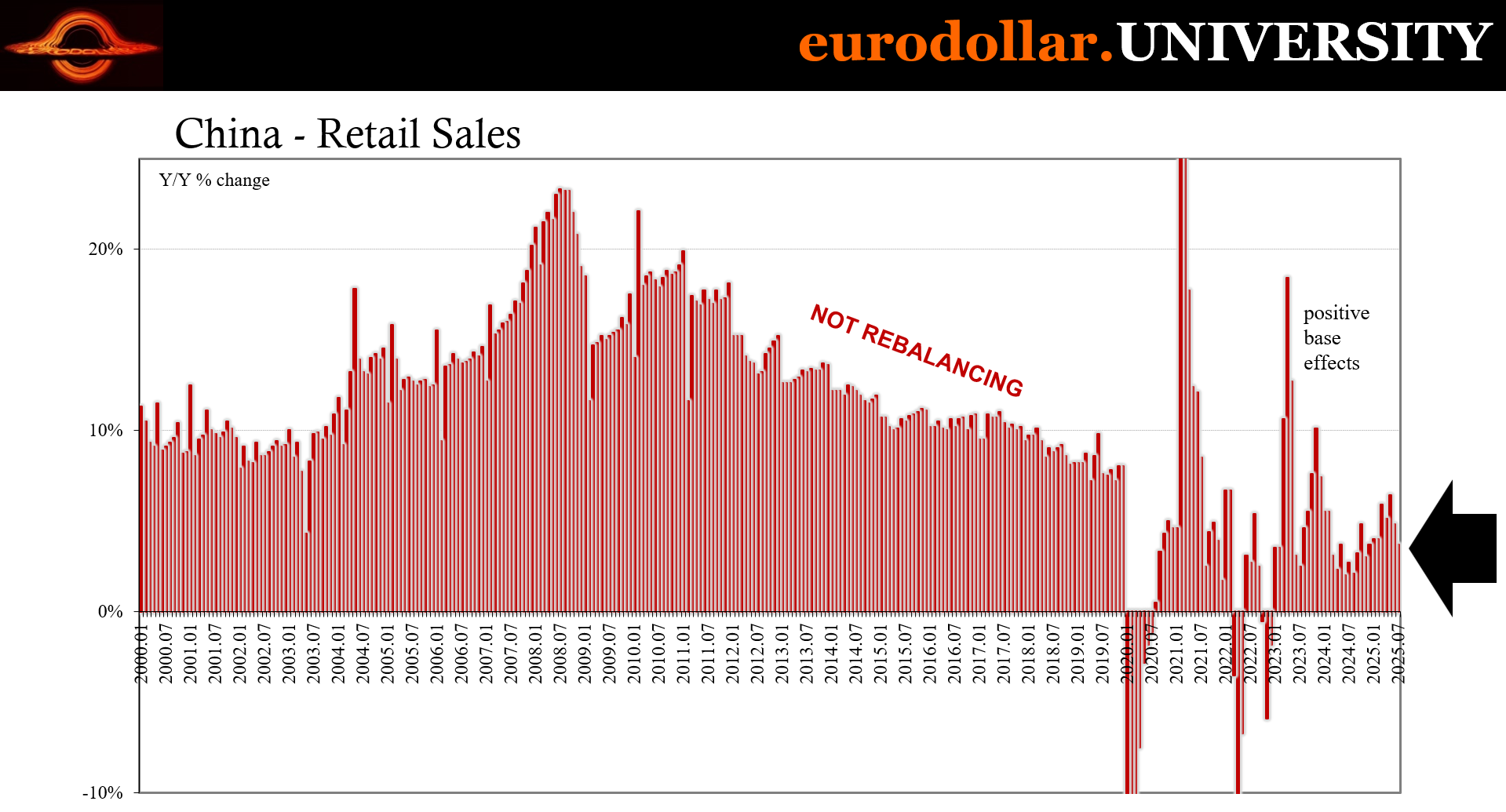

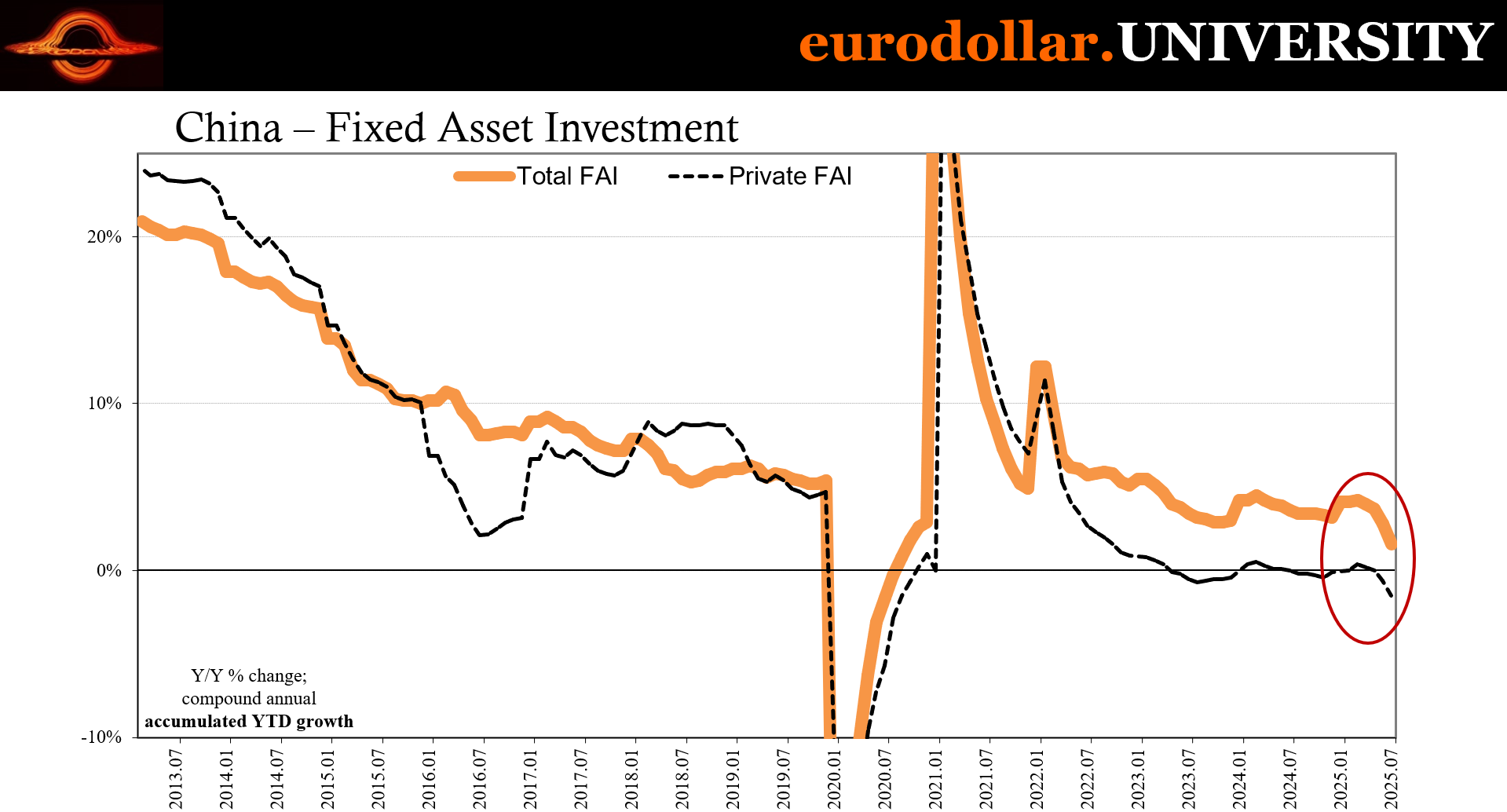

Summary: It’s time to talk about China. Something is up with it. In this case, that means neither up nor down for CNY as a start. Sideways yuan is nothing good, as history has shown. And goes with what’s being implied by the entire range of data coming out of the country for July. Banks in credit crisis pulling back more on lending. Now industry slowing significantly, consumer spending sharply contracting, and capital spending falling off a cliff. It sure looks like payback therefore of great interest not just for China’s sake.

WHEN IS SIDEWAY SUDDENLY INTERESTING? WHEN IT IS CNY.

The Chinese economy, financial system, and a lot more appear to have stumbled, badly, in the summertime. Where to even begin? There was the credit report I highlighted a few days ago. RMB loans contracted sharply for the first time in over two decades, pointing to something shifting underneath what has been a persistently difficult environment, to put it kindly.

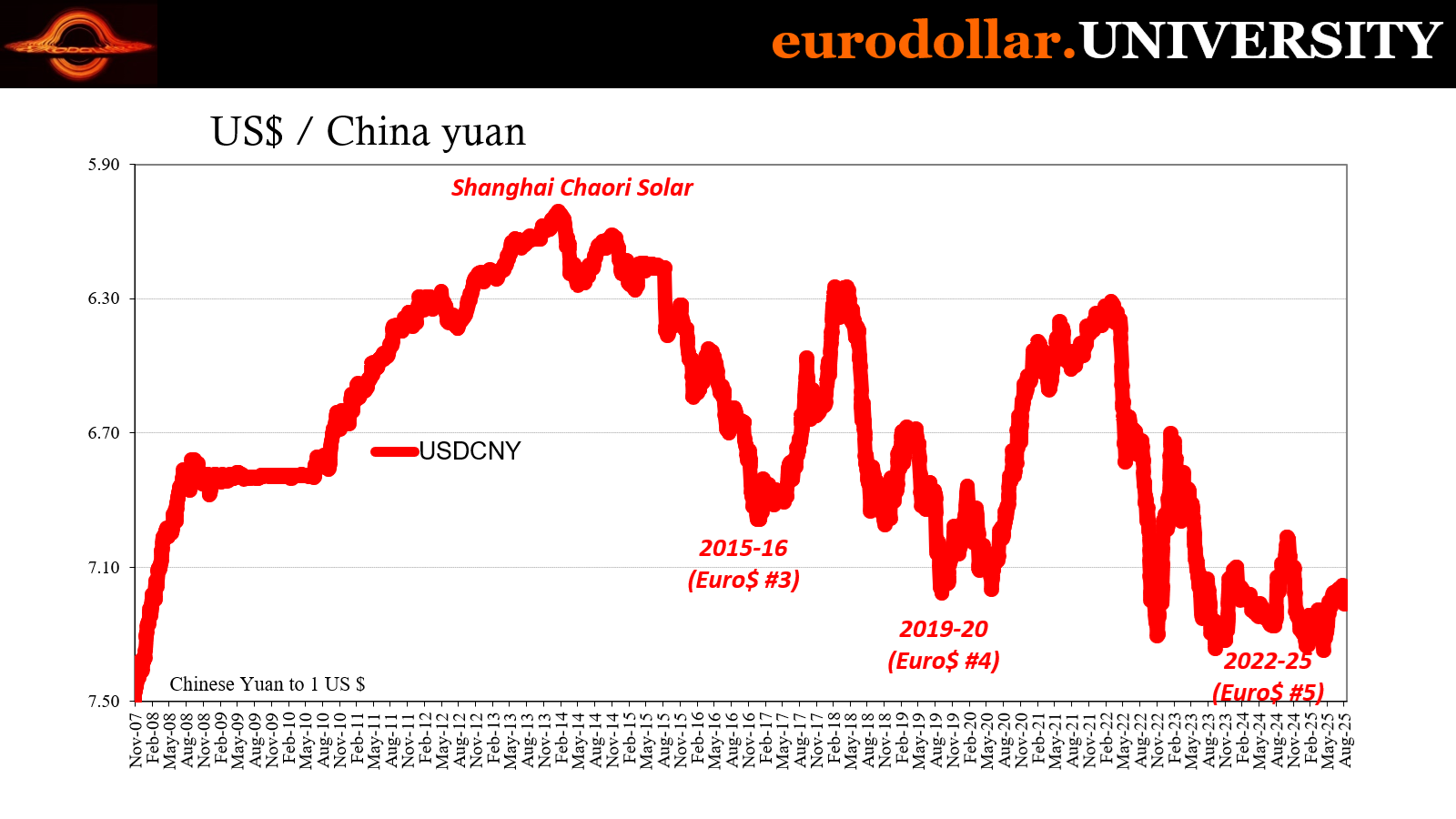

Part of the problem is we get accustomed to the downside where it comes to China. The country has been slowly degrading for years, going on a decade and a half since anything there could be honestly considered robust. Euro$ #2 hit the Chinese hard in 2011; starting 2012 it has been all downhill since.

Very slowly, of course. The ability of the CCP under Xi Jinping to manage that decline has been remarkable, though hardly laudable, yet should not be underestimated. They’ve also managed to make a mockery out of anyone calling for their collapse, either economically or politically. The two are heavily intertwined, meaning it has been in Beijing’s best interest to at least keep the downside limited even if that has meant zero upside.

More recently, though, it looks to be slipping. Since the price illusion in 2021-21, that decline has been slow and seemingly steady, to the point it gets to be almost imperceptible. That’s the trick; the pace has been so indiscernible it goes largely unnoticed, those of us who pay attention become normalized to the weakness and the data starts to look basically the same month after month. You can get lulled into apathy, shrugging it all off as a new normal.

There have been further warning signs and turning points, but since they fail to match those expectations for China’s imminent demise they just get lost in the noise of the slow, grinding downward trend. The first of them here in the 2020s was the failed reopening in 2023, with another coming last year in the banking sector (credit crisis). Now, we may be seeing another emerge and, so far, it is putting up some suddenly interesting numbers and results.

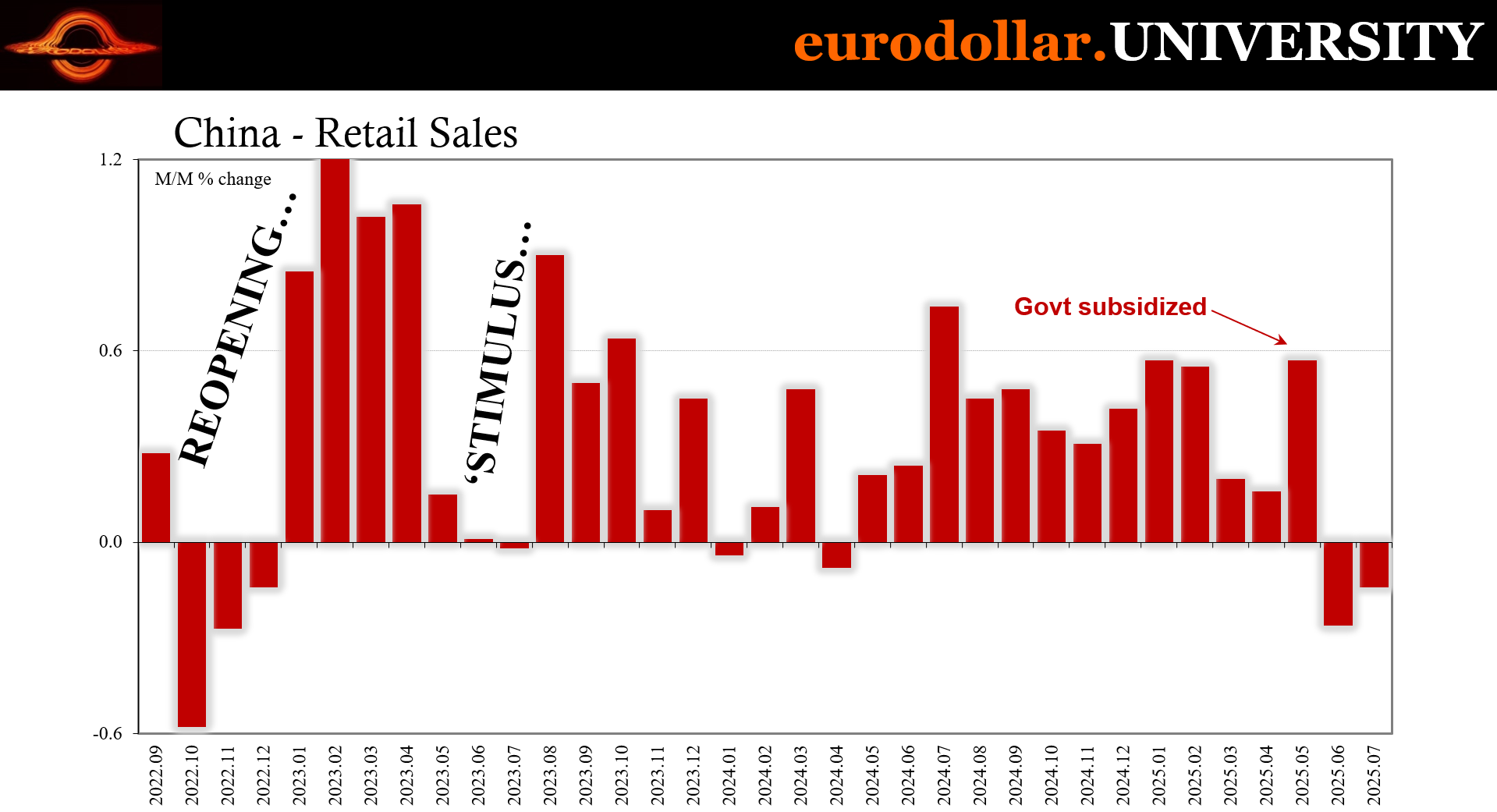

In addition to the new bank credit decline last month, earlier today the Chinese reported a major shift in their Big Three data. Retail sales have contracted two months in a row (monthly basis) while it appears fixed asset investment just fell off.

On top of all those, CNY is starting to resemble a pattern we don’t want to see – sideways.

China might be exhibiting more concrete signs of global payback coupled with its already-fragile state. The boring, every-month-is-the-same weakness didn’t show up in July, something else did.

Not sideways

The last instance of purely sideways CNY came just before the sharp, chaotic snap in August 2015. At the time, everyone wrongly accused the Chinese of “devaluing” their currency as a way to stimulate exports for an economy that was weakening for reasons everyone also couldn’t identify. After all, it was assumed Western QEs had worked as had general other forms of “stimulus” therefore China should have been moving back toward its precrisis form.

The fact that never happened simply never dawned on anyone, so naturally the consequences of getting that wrong didn’t, either. China was stuck in a downturn and reeling from the monetary blowback as the eurodollar began to zero in on CNY. Previous to 2014, everyone also assumed the yuan only went in the other direction, higher, only to suddenly see the backlash hit right when it shouldn’t have, had QE actually worked.

Timing wasn’t coincidental. In the aftermath of the 2012 slowdown (Euro$ #2), Xi Jinping began to manage China’s decline, late in 2013 letting a corporate default go through for the first time in modern Chinese financial history. Defaults weren’t “allowed” over there before, not during the nominally capitalist phase of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics. This had actually been one of the West’s most fervent complaints, how the Communists weren’t playing “fairly” when artificially propping up or subsidizing anyone remotely connected to a local government minister.

Once Shanghai Chaori Solar went bust and it became clear in this case Beijing would not step in, as it always had, the combination set off the “devaluation” in CNY the country is still wrestling with to this day.

It wasn’t an intentional currency policy, rather the reaction across the eurodollar world to an economy experiencing a radical and permanent downshift combined with the suddenly immediate financial dangers such an inflection stoked. The dollar’s rise against CNY was risk aversion, dollar tightening backlash as the whole system began to come to grips with a very different future course.

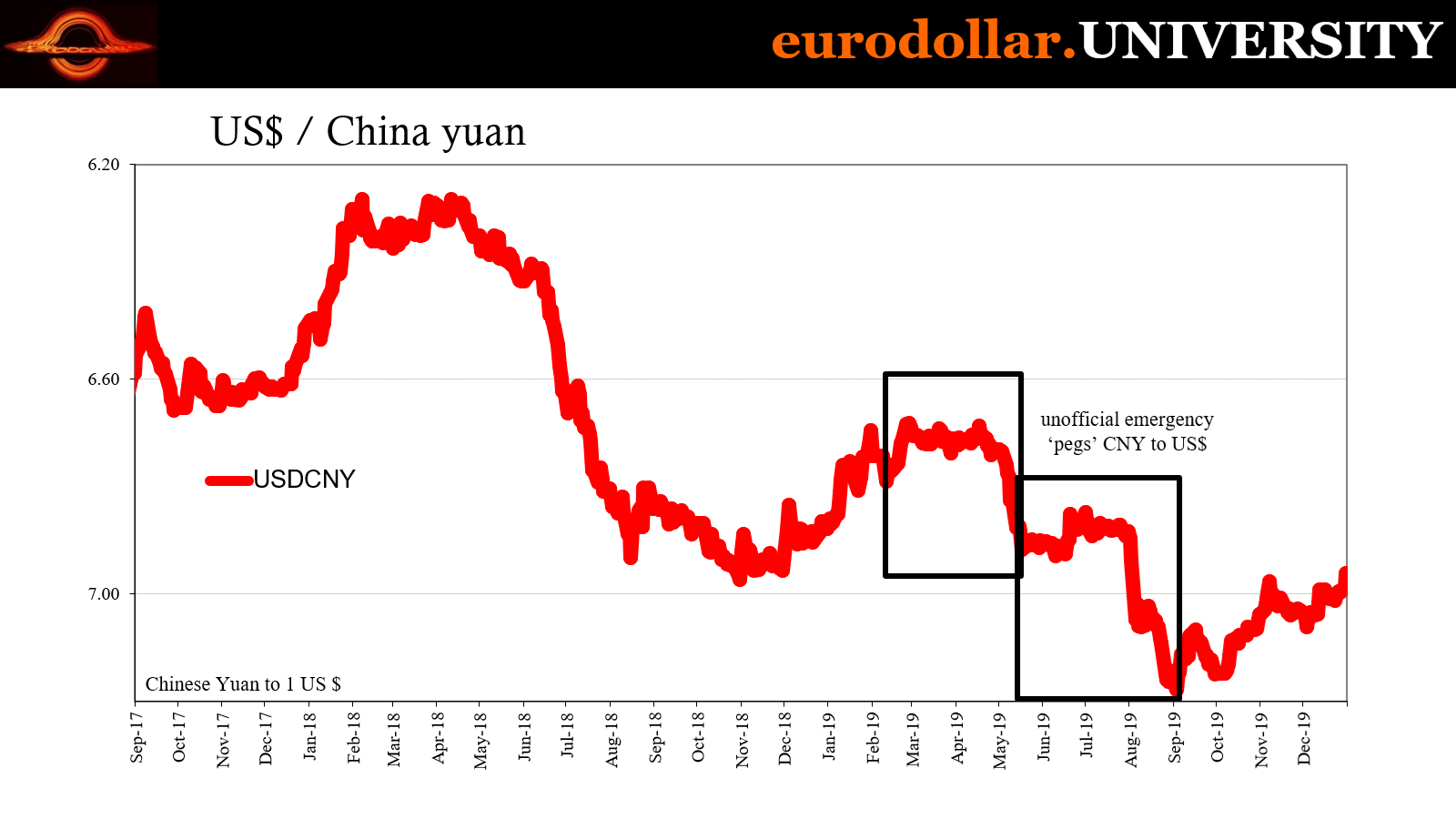

After a turbulent 2014, by the middle of 2015 the situation had grown critical. What were authorities to do? They enlisted the PBOC which further deputized China’s big banks to effectively peg CNY against the dollar – again. They had done something similar in the middle of 2008 during the leadup to the global crash later in that year.

The difference was it had worked in 2008. Recalling the tactic and the experience, why wouldn’t it again seven years later?

From mid-March until August 10, 2015, officials desperately by hook and by crook threw everything at the problem so as to keep CNY from falling. Devaluation it wasn’t. Q

The “dollar” shortage, however, only grew worse. In that respect, these actions probably, very likely contributed to the deterioration. I wrote way back on August 20, 2015: “…like a coiled spring, it could only remain in that state [pegged] so long as either the internal strain was manageable or the external pull of the “dollar” did not extend too far in time or depth.” By early August, the spring had been compressed too long and too much.

The whole thing snapped. Here’s how I described it just three days after CNY’s “unexpected” and stunning collapse:

So if the PBOC was no longer able to supply sufficiently as pressure exceeded some grand threshold, assuming that is what kept the yuan suppressed those five months, they had only two choices at that point – let the fix drop significantly so that China’s banks could find their “dollars” at whatever price or face illiquidity to the point of default, “dollar” insolvency and all the rest of the nastiest consequences.

As eurodollars became far more difficult to roll over from 2014 into 2015 - and not just for Chinese banks urgently seeking rollovers, also everyone synthetically short them around the world thus the rising US$ exchange value - that had meant eurodollar suppliers (collateral or cash) demanded a higher premium to do so. In the simplest terms, China would have to pay more yuan to keep up access to the necessary supply of the world’s actual reserve currency.

Eurodollars, not dollars.

But, before August 11, China’s banks were prevented from having to pay the market-clearing price(s) by the PBOC trying to maintain a sense of calm and authority by blatantly sticking to a trading range that was more and more divorced (too high) from the fundamental situation, forcing policy banks to effectively pay the subsidy by borrowing in FX then relending onshore (some offshore in HK) all to redistribute dollars to Chinese firms and banks.

From mid-March to just before August 11, the pegging of CNY really meant that functionally China’s central bank was clandestinely sponsoring commercial banks’ private attainment of US$s on the global market.

It all reached a critical state and then blew up. As I wrote back then, the PBOC quite understandably “let the fix drop significantly so that China’s banks could find their ‘dollars’ at whatever price” because the backlash, the eurodollar tightening had become too fierce and deliberate to keep the peg any longer.

The coiled spring just snapped, as over-coiled springs tend to. As it did, that was a signal how serious the global climate had gotten to be.

Current coils

Since 2015, the PBOC has been far more careful about abusing the tactic. There haven’t been any additional informal pegs, not to that blatant degree. That’s the thing about them: authorities never said that was what they were doing, and the media never caught on to why they might. For their part, PBOC policymakers did keep everything at arm’s length, making banks literally do their bidding and creating plausible deniability.

The effect was the same either way. And China did learn a painful lesson, which is why their actions the next time in Euro$ #4 starting 2018 were overall very different (I’ll save that for another time).

No more pegs.

There have been a few times when CNY gets close. One - actually two - of those was in 2019, sideways trading if not as straight as 2008 or 2015. First, from February to April and then between May and July. Yuan would hang around and then, like August 2015, fall off a cliff, plummeting from 6.70 in starting February in two big moves reaching 7.18 almost 7.19 by early December.

The timing of those plunges was no coincidence, happening at the same time as the “recession scare” in US and on global markets (adding more evidence it wasn’t only a scare). Just like 2015, the snapback in the coiled spring was a signal.

Over the past few years, every time CNY has dropped “too far” coming within reach – even at – the lower daily limit, the exchange value falls to suspiciously low volatility. It is clearly the same type of intervention, big banks borrowing FX and redistributing/relending dollars in the cash markets, just less blatantly obvious than 2015’s unofficial peg.

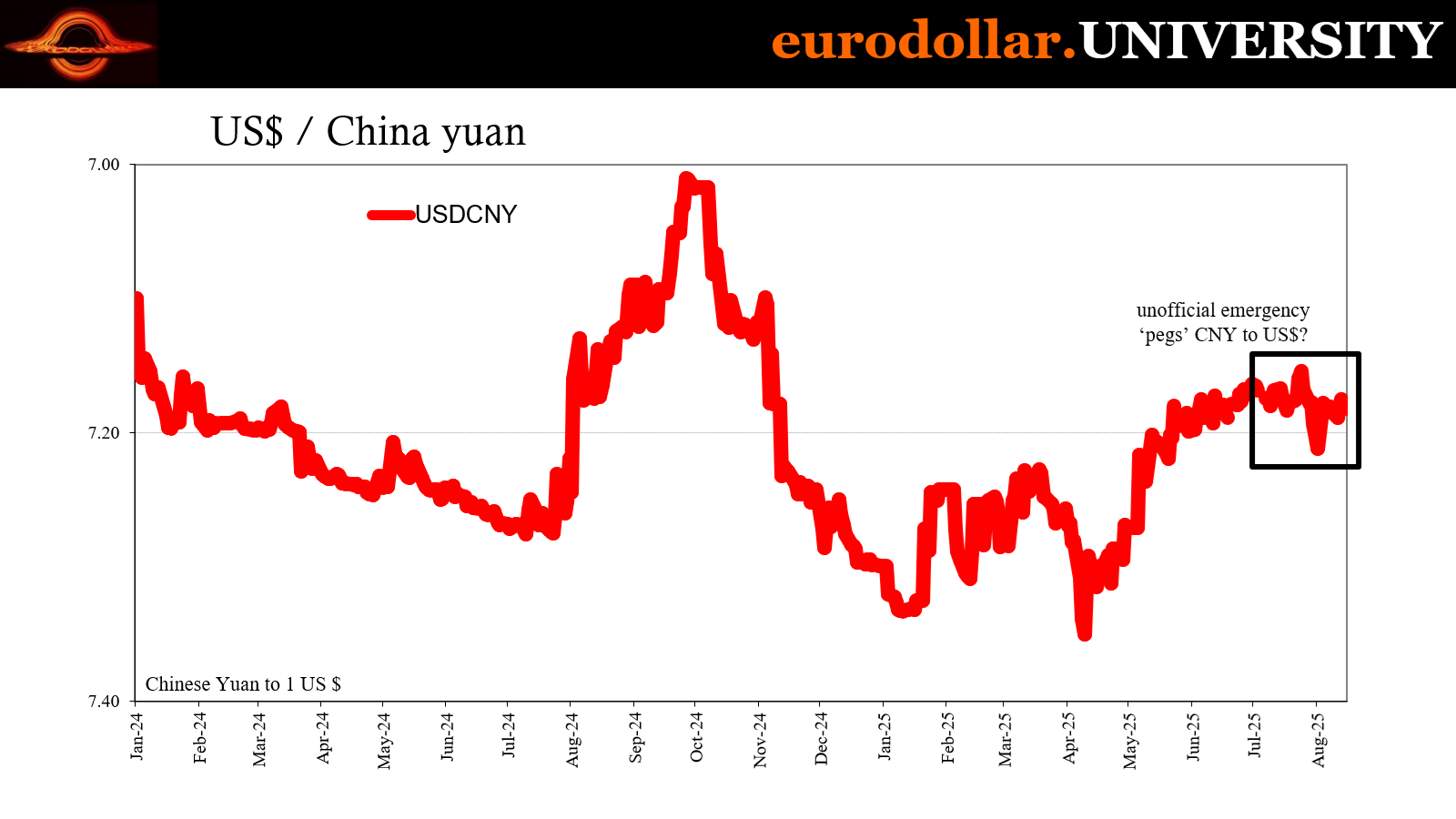

In our current example unfolding right now, it’s definitely not one of those, either. Yet, there is or should be no doubt “something” is going on with CNY. To begin with, this something started exactly on July 1. Try as they might to hide their activities, the Communists can’t help themselves sticking to round numbers and even calendar intervals. The yuan began the second half of the calendar year by halting its previous rise.

That rebound in CNY had come about during the tariff delay phase of these “trade wars”, dating to April 9 when the Trump administration pulled back. Over the several months afterward, outlines of trade deals came into focus and eventually some agreements were struck. From an emotional standpoint, the world seemed to back away from a serious ledge, thus the relatively more favorable positioning for the yuan.

It wasn’t quite re-risking and full reparation as in stocks but taking CNY from its seventeen-year low at just above 7.35 (with CNH crashing into the 7.40s) up to around 7.16.

From there, July 1, no more improvement at the time volatility has clearly diminished (though not entirely). It isn’t a peg, as I said, however it is there. We’re seeing sideways CNY emerge and like 2015, to a lesser degree, that’s not going to be a good sign. It suggests building pressures for what should also now be increasingly apparent reasons.

China’s credit crisis is getting worse, having taken a bad step in that same month of July. Now the economic data for last month which shows consumers contracting, industry slowing, and FAI totally cracking. Something big is up, yet CNY isn’t going down.

Holy grim

Industrial production in China has slowed down, though not nearly as much payback (yet) seen in places like Europe (the other key global economy showing more concrete signs of it). The rate slipped to just 5.7% y/y in July, down from 6.8% y/y in June and a high of 7.7% back in March. Nothing catastrophic, sure, but a clear slowdown and establishing the downslide toward payback.

Retail sales, however, have been weakening the entire time, too, but to a far greater extent and reaching alarming proportions here. The y/y rate peaked at 6.4% two months prior on the direct support of government subsidies for goods like electronics and appliances. For May alone, retail sales jumped by 0.57%.

That was the only decent month since February. The downturn started with March (like a lot around the world) seeing the monthly rate in sales sliding to just 0.22% followed immediately by a worse 0.16% showing in April. After May’s artificial high (how many of these have we seen this year?), Chinese retail sales have contracted each in June and July.

This has left the annual rate dropping back to just 3.7% and leaving the Chinese economy with more powerful questions besides the grim numbers. Not only is consumer spending faltering badly again, doing so proves maybe once and for all there is nothing Beijing can do about it (adding to perceived risks). Authorities can prop up retail sales for a month at a time, at most, yet all it does is buy a tiny amount of time – just like a softer peg to CNY might.

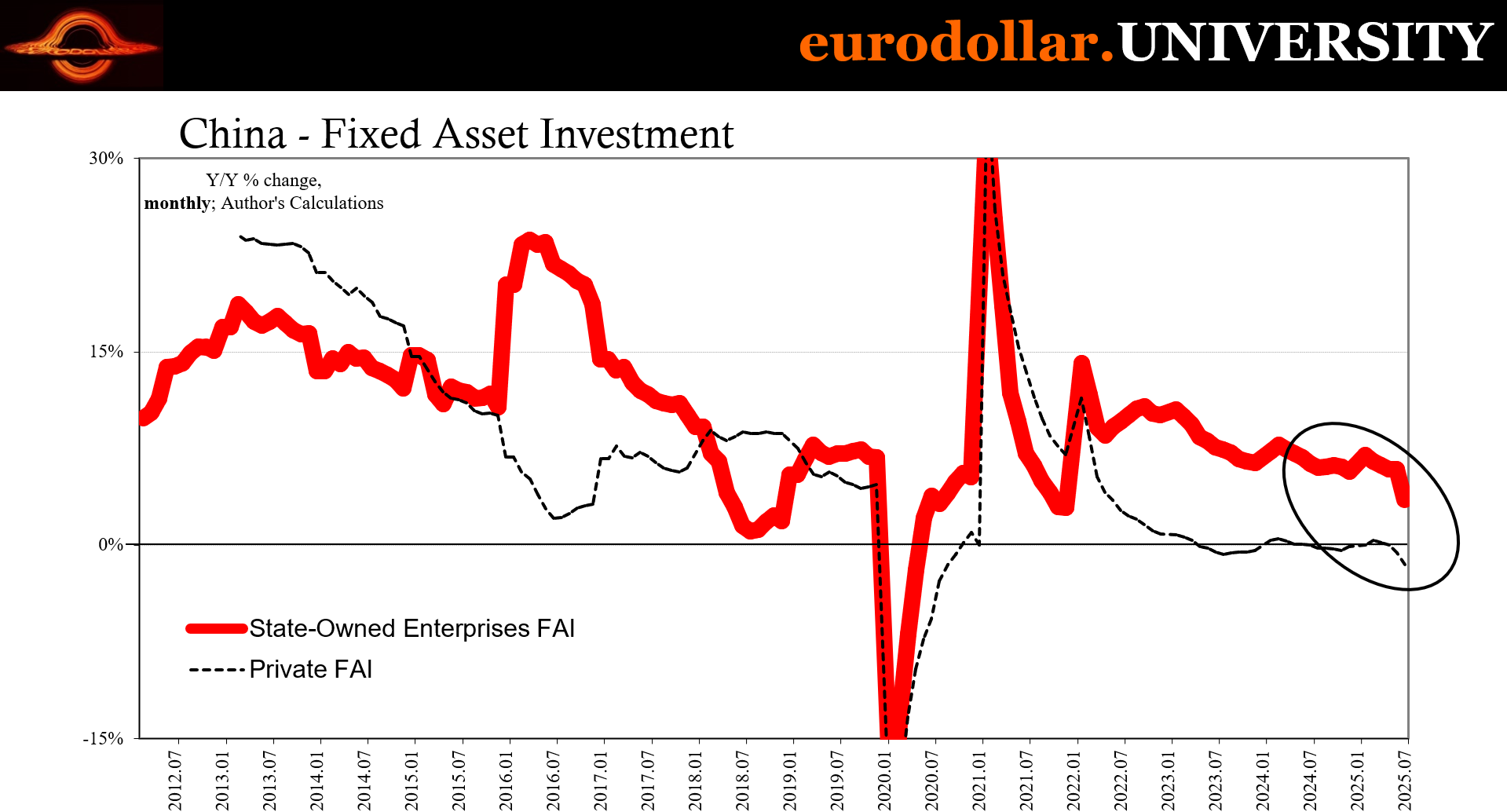

However, fixed asset investment managed to take the contraction several steps further. Forget all the various government-led property sector “rescues” that have completely failed. Before now, FAI and general investment outside of real estate had kept capex in China relatively stable even if moderately contracting. “Something” snapped the past two months, same as retail sales.

The accumulated rate growth rate skidded from 3.7% in May to just 1.6% as of last month. That’s an enormous slowdown for an accumulated rate in only two months. Doing a little bit of math, it suggests a 0.6% y/y drop in private FAI during June then a huge 1.6% y/y fall in July. Even the PBOC’s monthly chained rates (which are subject to massive revisions that make the BLS changes to payrolls look credible by contrast) showed a near-zero rate in June followed by an oversized 0.63% decline last month.

It wasn’t helped by an equally large setback in investment among state-owned enterprises (SOE). Everything fell off to some extent in July, with only IP seeming reasonably normal, or what we’ve come to see as typical for China’s managed decline. Apart from that, consumer spending cracked and FAI crashed.

Stimulus isn’t just failing to stimulate like always, the other side of that failure is getting to be really concerning especially when paired with the credit crisis and its likewise severe impact on banks. As a result, weakness in CNY should be a given, so its absence is curious, to say the least.

Both the yuan as well as the economic data point to a possibly severe payback looming in China, which would not be the only place to suffer from it. The Chinese have been in a difficult spot to begin with, to the point that grim stats had gotten to be monotonous noise. These numbers and prices are definitely ugly but in what appears to be a new and suddenly interesting way.

Interesting in this context is never good.

Something definitely hit China recently. We have a decent idea what it is, even if the PBOC is again trying to cover it up with sideways CNY. It certainly bears watching for China’s sake, just as much for potentially representing the other side of the global artificial high earlier in the year, for what we might learn about the severity of the growing downside heading through the second half of an-already interesting 2025.