MAX MFI UNCERTAINTY

EDU DDA Apr. 29, 2025

Summary: European bank data showed another massive increase in MFIs already-considerable government bond holdings. That makes three straight months, with mid-2020 the only period with more. The only other two comparisons are 2009 and 2012. In short, European banks are up to something serious. Recession risk is one thing, but what unites each of these prior times is monetary deflation, with crisis proportions. In addition to examining those, also an update to America’s Beveridge Curve and how it aligns with plummeting consumer confidence.

THIS ISN’T ANOTHER ONE. SOMETHING IS ROTTEN IN THE STATE OF EUROPE, THOUGH.

The other day, Germany’s government declared 2025 a likely lost cause. Another one, that is. The German economy is slated to forget how to grow this year like last year and the year before. What was supposed to be the beginning of a tepid recovery has been put off for yet another time. Rather than the dazzling +0.3% “growth” previously forecast, that was downgraded last week to zero. Following small contractions in 2023 then 2024, though there isn’t much difference, this still counts as a disappointment nonetheless.

Sideway is bad, but sideways for three years is a borderline disaster no matter how unappreciated and unofficial. By the numbers, German GDP hasn’t even experienced two straight quarters of negative real output. Doesn’t matter, the scale of the decline is immense anyway. The issue is time now, not small negatives or positives.

As much of a dangerous sore spot as this has become, I still doubt it is responsible for making European banks near-historically crazy. The entire group of MFIs, as they’re known, has done something seen only once before. Over the first three months of this year, the entire banking sector there has added a truly astounding €180.2 billion in government bonds to their already-sizable holdings.

The only comparable period is March, April, May and June 2020. That’s it. During the worst of Euro$ #2 right when that monetary crisis built into full-blown recession in early 2012, MFIs piled on €130 billion during that year’s first quarter. Before then, the first three months of 2009 saw €143 billion total.

Nothing else.

So, yes, what’s taking shape among European banks is significant and worrisome. I highly doubt this kind of defensive, this degree of it, is because Germany is likely to “stagnate” for a third straight year, as bad as that truly is. And there will be fallout from it, as there already has (ask Mr. Scholz). Yet, that doesn’t lead to near-historic bond-buying.

The Germans are blaming tariffs for their downgrade, and why wouldn’t they? It’s a convenient excuse, not to mention sounding plausible. Either way, that can’t account for 2025 let alone 2023 and 2024. The word we keep coming back to is fragile.

That’s the term I believe is driving these remarkable results. On par with 2009, 2012 and 2020, this doesn’t leave stagnation as an option, not when considering what is common between all three years – bank crisis.

I’m not suggesting something like that, yet we can’t deny the possibility nor the potential for some kind of systemic spillover even it doesn’t mean a wave of bank failures, especially given the events of the first two on that list and how much European MFIs were responsible for each disaster, and each one becoming global.

The other word we have to keep in mind beside fragile is interconnected.

Beveridge update

Before diving further into European banks and their tangled relationships, first an update from today’s grim news and reports here in America. While JOLTS wasn’t horrible by any means, Job Openings did tumble which means the Beveridge Curve moves further toward the flat part. Meanwhile, the Conference Board’s consumer confidence estimates plunged, mainly on expectations, to where that particular index utterly crashed to its lowest level since 2011.

We are getting way too many of these comparisons of late, as noted already in the introduction. Those weren’t the only examples, as the final Fed regional PMI for April came in with its own plunge. Dallas’s service sector index dropped to its third-worst of the last half-decade, in so doing put the average of the five in services for this month at a new low – lowest since May 2020, meaning yet another one.

With Job Openings dropping back to 7.19 million, that placed the job openings rate (BLS version) at 4.32, only fractionally more than September’s 4.29 low. With the unemployment rate at 4.2%, March now marks the month furthest down and right on the chart/curve. Same for our adjusted job opening rate (lopping a million off Job Openings to make it less overstated), both closest to the flat section of Beveridge.

The thing is, the Conference Board like UofM or other confidence measures is being driven into the basement by fears over jobs and incomes. The Board specifically mentioned unemployment expectations: “Notably, the share of consumers expecting fewer jobs in the next six months (32.1%) was nearly as high as in April 2009, in the middle of the Great Recession.” In short, consumer confidence is implicitly yet strongly indicating the same transition on the Beveridge as the BLS data.

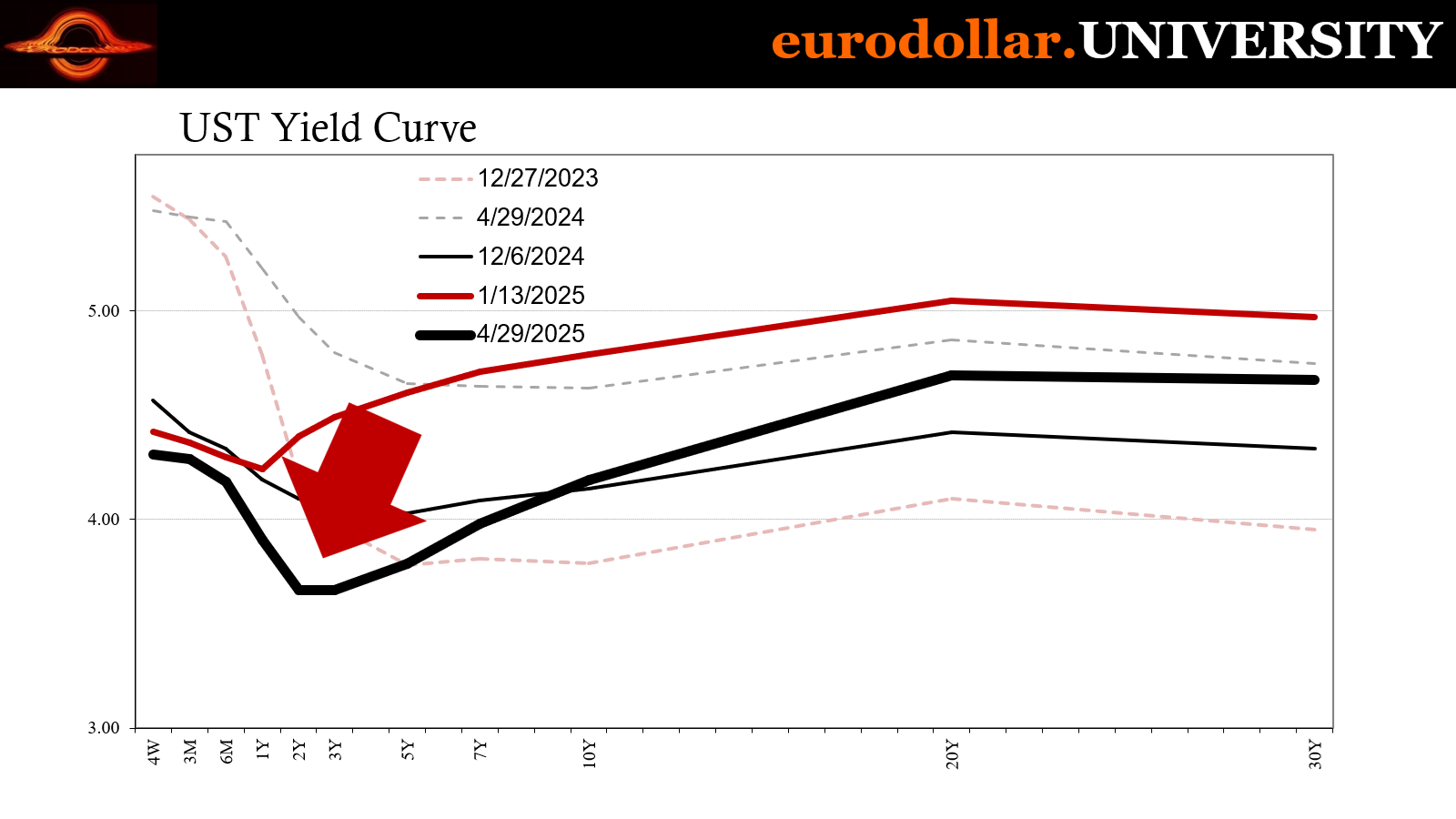

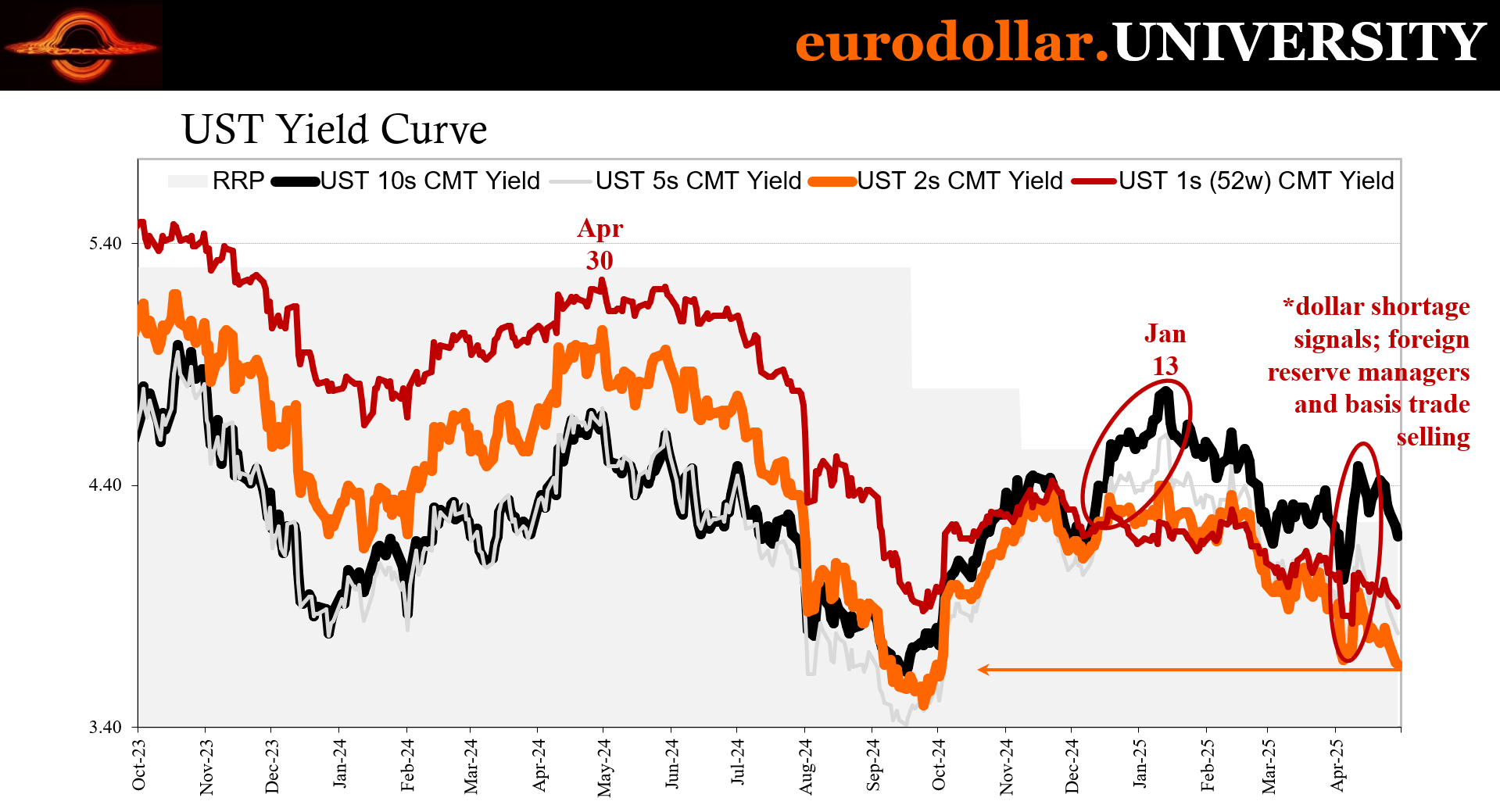

It is that same implication which today pushed the two-year Treasury note to its lowest yield since the second day of October, now closing back in on the September cycle lows. In fact, when you look at the yield curve itself, the obvious bulge right in the middle starting with the 2s is a similar type of warning as European MFI govt bond buying, if not quite (yet) to that intensity.

This is defensive as hell, classic bull steepening seeing economic risks and maybe more rising sharply here in the short run. Given what I just wrote in this section, that, too, makes too much sense.

No Berlin bazooka detox

I half thought the MFI balance sheet data for March would show European banks backing off their safety push. For one, early last month the incoming government in Berlin had announced its intention to “stimulate” the economy at a record pace. Once in power, it would remove the so-called “debt brake” and then begin spending in a way rarely seen in that country outside Weimar or WWII.

Though it’s a shame of a massive waste, and won’t accomplish any of its goals or even get within sight of them (as history conclusively has shown), initially, anyway, the bond market backed up. As I wrote and said at the time, faced with a new “bazooka”, sell safety and see where it goes. Maybe in different circumstances, it might have had a little more time with higher rates. In 2025, there is worse on the short-run horizon than there had been in 2024, so rates never went far and immediately turned back around.

Still, I did think for a few seconds it may have dissuaded some banks from continuing to load up on government securities. Apparently, that never happened; or, if it did, the second-guessing was quickly cast aside to get right back into it. The relentless bidding doesn’t appear to have been interrupted at all by the bazooka, which is yet another warning sign.

Does that include space for collateral difficulties, or monetary disorder more broadly?

That’s another key component in all three of the prior comparable periods. In early 2009, 2012, and then the middle months of 2020, there were obvious monetary difficulties heavily driven by collateral shortfalls. Given just the scale of what’s gone on – an increase of nearly 10% to government bond holdings all in Q1 alone, and a total increase of 25% just since last January for MFIs – it’s a consideration we have to take seriously.

Collateral in there?

As we do look seriously at the possibility, we first have to realize this means a lot more than European banks and euros. There are close connections all over the planet, including those between Japanese banks and all their eurodollar counterparts. In fact, Japanese banks will often borrow dollars from American banks (or related offshore) to then invest in euro-denominated assets brokered by European banks.

And when the Japanese have occasionally run into trouble, they’ve been “bailed out” by European eurodollar redistributors who borrow dollars in Eurobonds, take the proceeds to the Japanese who swap them euros as collateral. Geography means very little in the eurodollar’s world

The very spark of full-blown crisis in August 2007 was European, and the initial ripple of repercussion was Japanese. Seeing the deflationary conditions erupt in offshore markets at the time, FOMC officials wondered if it was a London problem or a dollar problem. In truth, it was both and that ended up being the whole catastrophe.

Where it comes to collateral, there is a bit more to it (as always).

Start with something called “regulatory arbitrage in the presence of non-harmonised re-hypothecation regimes.” Though very few humans on this planet can make much sense of what seems otherwise a nonsensical jumble of misused words, the implications are considerable.

To begin with, ask any person about the 2008 crisis and ninety-nine out of hundred will tell you it was subprime mortgages, those greedy Wall Street bankers making stupid loans to American housing bubble buyers in no shape to borrow for even the most reasonably-priced property. The hundredth will simply say “they” crashed the system on purpose.

Challenged, this near-centenary might go further to allege that these ill-conceived mortgage loans, being so badly packaged and at times illicitly maneuvered, these obviously created huge losses for the banking system which provoked good-thinking people to remove their money before being drawn into the orgy as it inevitably imploded.

Like Lehman Brothers.

A classic case of currency elasticity in the 19th century mold; an ol’ fashioned bank panic.

There were, actually, very few cases of this; only isolated instances. These certainly made for good television, especially during an election year in the US, and they did serve to leave a specific impression about banks being banks and doing what banks always have done. Long lines of depositors desperate to convert their deposit claims into bearer currency, cash, just didn’t happen except for rare examples (like Northern Rock in the UK, or IndyMac in the US).

Lehman Brothers, by the way, didn’t even have depositors.

Of those big banks who did, like Citigroup, it is true they experienced huge losses. Tens of billions, but not because of subprime mortgages. These were proprietary write-downs (OTTI; other-than-temporary-impairment charges) as large warehoused securities they were holding, or were stuck as beneficial owners of, grew unstable due to severe disruptions in the marketplaces for them.

What had made these massive, complex securities markets so unstable? Furthermore, why were these disruptions spread out all over the world? US subprime mortgages should have been contained to a US subprime mortgage problem, instead it grew to become a gross, global bond and fixed income expurgation. While Lehman Brothers had been at the center of it, very few today understand what was the center of Lehman Brothers.

Just as the untimely unwinding of AIG is mistakenly put down as some issue with some derivatives called credit default swaps, in truth what brought AIG to the brink was largely the same thing which pushed Lehman Brothers over it. Securities lending practices, not trigger-happy depositors.

For one thing, Lehman Brothers Inc. was merely the US dealer of a global dealer network housed under a single parent with that name. Counterpart to the American Lehman was the London-based subsidiary Lehman Brothers International Europe. Both prime brokers serving a range of big financial customers, including other brokers and dealers, as well as hedge funds, the London sub had a huge advantage its American cousin couldn’t match.

Regulations and regulatory arbitrage; it was purposefully made much easier to do monetary business in the offshore network of which London’s Lombard Street had been the key node. British authorities long ago decided in order to be a player in the growing international currency regime of the eurodollar system they’d let international banks setting up shop in The City do a whole lot more of what they wanted so long as their customers weren’t British persons.

This meant, among other things, any of these “London” banks and subs could offer clients much better terms, so long as, in most cases, clients went along with the full particulars of this arrangement. Including, getting back to our beginning premise, what amounted to a non-harmonized rehypothecation regime.

Clients buying securities through Lehman Brothers Inc. may or may not have been aware that the end result was those securities actually being custodied with Lehman Brothers International Europe across the Atlantic. In most cases, they wouldn’t have cared anyway; the latter dealer offered much better terms, funding arrangements and other perks that cheapened the costs of doing financial business. All a form of leverage.

This leverage extended to Lehman, too. Because in the world of securities lending, and what today is called securities funding transactions, to get the best terms mostly means letting your broker secure them on your behalf.

Nobody buys securities; they borrow and claim to “own.” Repo. The hedge fund (client) says it wants to own XYZ US Treasury issue, puts up a minimal upfront investment, enough to cover some overcollateralization requirement, and borrows for the rest of the purchase price. In many instances, the broker is the lender as well as custodian.

To make this securities funding transaction as cheap as possible, the client will agree to allow the dealer to re-pledge or rehypothecate (for our purposes here, the language is interchangeable though in a legal and regulatory sense these terms can have different meanings) the very security the client is claiming to own.

What that means is the dealer acts as an intermediary rather than lending its own cash for the purposes of the client owning this particular security. Instead, the dealer will repledge that security in the repo market or to other dealers in order to borrow the cash ultimately used to “purchase” and then fund the transaction (rolling over) to its ultimate end. Not just a securities financing transaction, a whole series of them.

And this series becomes horizontal as well vertical; the already re-pledged security posted by the client’s dealer to the next dealer in line can be re-pledged again depending upon the conditions set forth between the client’s dealer and what is now the client’s dealer’s dealer. As you may already guess, the client’s dealer’s dealer may also be able to re-pledge – the same security – to its dealer; specifically, the client’s dealer’s dealer’s dealer.

In many if not most cases, there needn’t be the original client need for this chain of re-pledging, either. What I mean is, the first link in that chain doesn’t have to originate out of the client’s need to borrow directly; if permissible, the client’s dealer may re-pledge the client’s security(ies) for its own purposes, with the client being sufficiently incentivized.

Thus, a dealer who does this kind of business with many financial clients can build up a stash of usable collateral that it doesn’t exactly own; these securities belong to other firms and vehicles, but are more than useful for the dealer to fund and carry out its dealer activities as a whole because of these peculiar usage rights.

The permissibility of these kinds of doings is, and remains, much higher in the offshore domain (the non-harmonized part of these rehypothecation regimes). The more a dealer could do re-pledging for themselves, the better terms it would offer its customers; giving Lehman Brothers International Europe a serious leg up on Lehman Brothers Inc.

Net result, Lehman Brothers as a global firm had acquired a significant pool of collateral owned by its customers and custodied at Lehman Brothers International Europe which underlay a whole range of dealer activities carried out by Lehman Brothers Inc., including securities financing transactions in its own proprietary book as well as a creating a margin collateral cushion for a whole host of derivative transactions and potential counterclaims.

So, what happens when customers start to feel a little uncertain about these arrangements? Quite naturally, they may begin to wonder about what their exposure might be given how their securities are in London. In fact, this, not subprime mortgages, is what led to Lehman’s end.

Hedge funds and dealers as Lehman clients scrambled to change these prime brokerage agreements limiting Lehman Brothers Inc. from being able to transfer assets into Lehman Brothers International Europe, or demanding they be transferred back, having the effect of stripping Lehman of a huge chunk of what had been available collateral by which to supply its global operations.

The rest was typical, traditional bank run stuff; rumors of Lehman being shaky led to the initial customer collateral “run” which then made Lehman shakier leading to more customers running in and changing their brokerage language. Soon enough, bye bye Lehman.

It was a run, but it wasn’t like one Walter Bagehot or Benjamin Strong would’ve recognized. It sure hadn’t been something Ben Bernanke or any of his kind considered too important, either. The latter group, contemporary central bankers, focused instead on the level of bank reserves, even as the federal funds effective rate had plummeted and been undershooting for a year by then.

What’s truly maddening is that authorities in the official sector have, and had, all the data – and absolutely no idea what to do with it. They have access to confidential streams, call reports, can pretty much open any book like any bank regulator in the past has been able to examine. They lack, however, the frame of reference so as to properly interpret this data no else has access to.

The real matter here, however, is that collateral providers are keenly aware of these matters. So are regulators, who developed that godawful terminology. Rather than help, at times it becomes another stress point with repercussions spanning the world. Sometimes being made aware of certain risks makes everyone more sensitive to them.

This doesn’t mean that a similar 2008- or even 2012-style crisis is emerging from the MFI fog for 2025. However, there are – and have continued to be – monetary difficulties related to how this patchwork eurodollar world isn’t as seamless and flexible as it once was. These frictions can become more than complications, transforming easy, dependable funding into a confusing tangle of impenetrable interrelationships that aren’t worth the trouble.

And we’ve seen more consequences in global liquidations of significant proportions twice in recent times – this month and last August, with the fallout becoming more severe with each successive eruption.

One way to protect oneself is to do the very thing that banks did in early 2009, 2012, and mid-2020. Greatly expand the on-balance sheet access to collateral. Like with US primary dealers who load up on Treasuries anticipating collateral difficulties to profit from them, the same goes for euro-denominated dealers, too.

There doesn’t need to be a full-blown collateral run, either. During the deflation of early April, while there were hints and indications of some collateral difficulties, nothing like those earlier crisis periods. There was enough to create major liquidations in commodities, stocks, etc.

Even Treasuries.

What MFIs may be seeking protection from, or to profit off of, starts with fragile and then encompasses interconnectivity. Fragile as in a real economy that wasn’t in good shape – especially Europe – now faced with even a small shock which might turn into a bigger bout of disorder than it otherwise would have in a truly robust period.

But also, as we got a taste of earlier in the month, the rather painful and sharp financial reactions to that as only a possibility. There was no outright recession, yet the clear distressed sales and liquidations point to severe dislocations anyway, including maybe especially Japan!

The bottom line is MFIs are up to…something. It isn’t another year of “stagnation” in Germany that accounts for it, no matter how dangerous that might be all its own. While it doesn’t prove anything seeing bond-buying comparable only to 2020, with 2009 and 2012 the only other close comparisons, common sense alone does dictate close examination and scrutiny.

It’s not like regulators are going to do it.