A VERY OVERWHELMING VIBE

EDU DDA Sept. 12, 2025

Summary: It isn’t just right, it’s significant. More and more Economists and their like are admitting consumers were right. Their dour “vibe” the past few years really had been right after all. This isn’t merely an academic exercise meant to relitigate the past, however. Instead, if Economists are throwing in the towel on the upside, the same might be true for employers and then the shift in thinking becomes more than just, well, sentiment.

A sea change in the thinking of Economists as a class proposes, and maybe parallels, something real taking place in the real economy. It may mark that very point of no return, when detached (and otherwise useless) commentary shifts recognizing there is no going back. If they are forced to arrive at that conclusion, then who else not so preprogrammed?

Easy enough for Economists who simply change their numbers and their forecasts with little offered introspection. What about businesses, employers? When these latter throw in the towel on the economy it spells Beveridge.

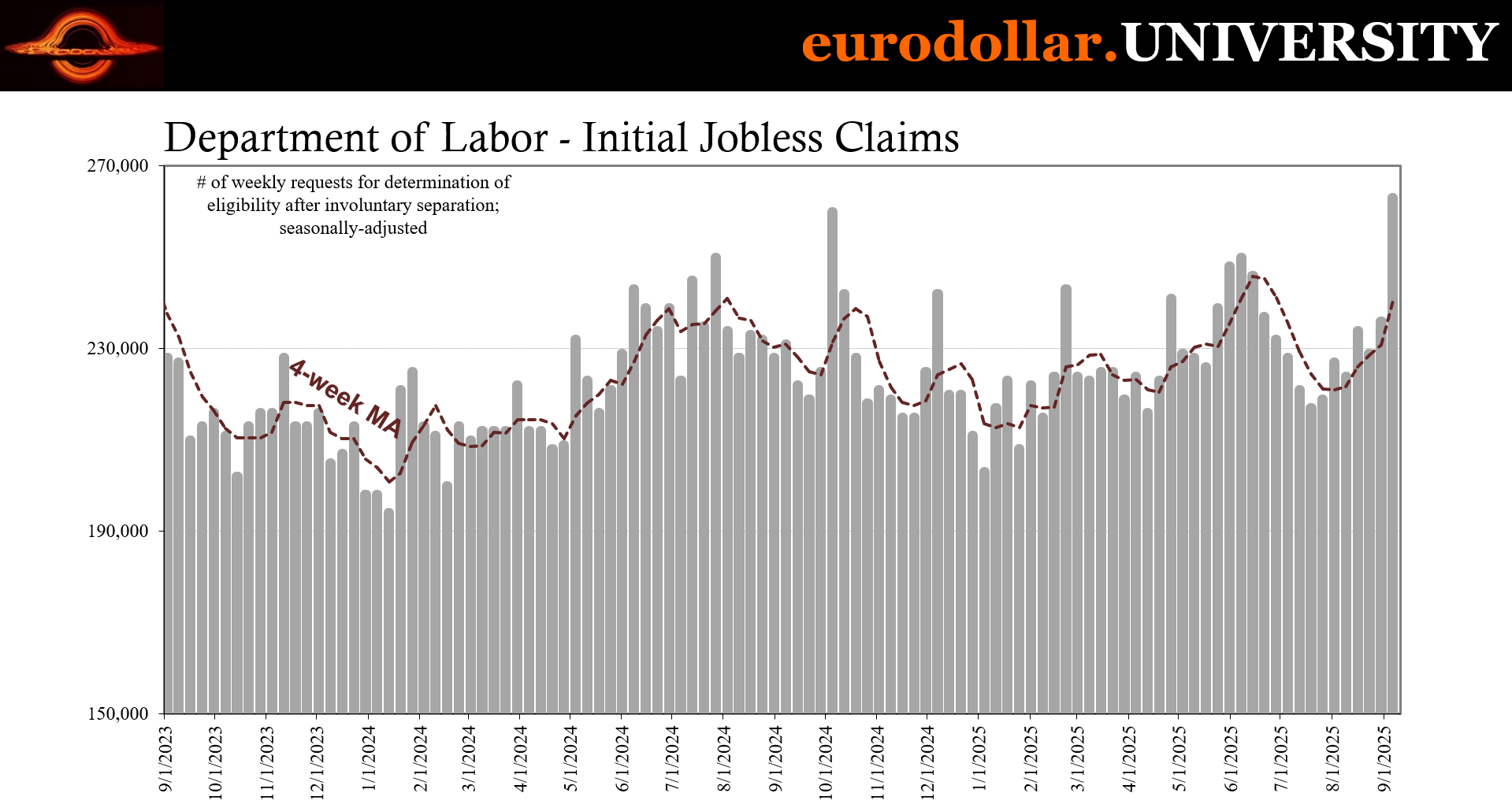

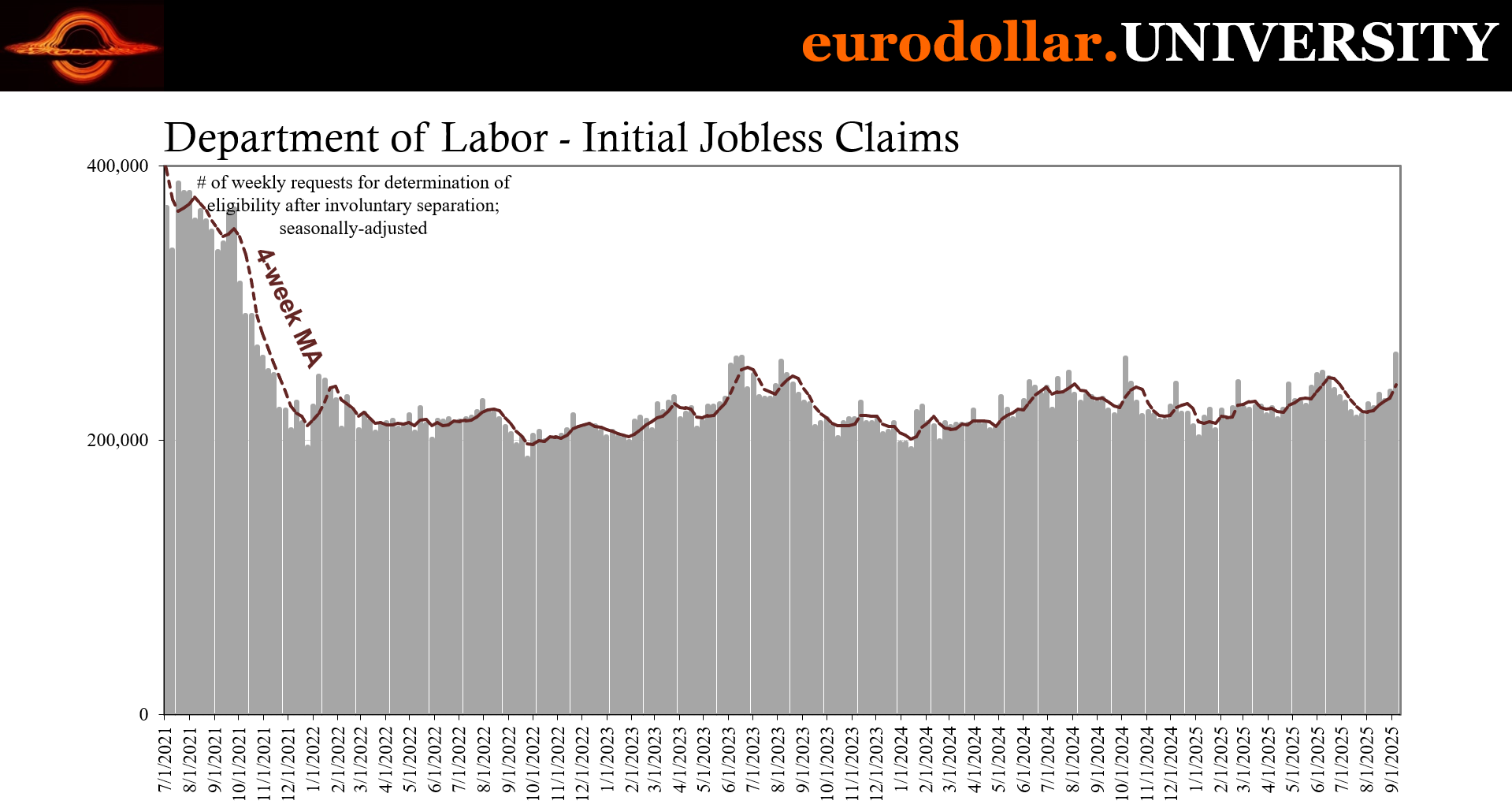

Thus, watching Economists and their perceptions may lead to some useful insight into the broader thinking of those in the economy who do matter. What we’re seeing right now is something that looks just like that. It may have begun in Texas with the oil business, the reason why initial jobless claims surged the way they did this week.

Energy firms appear to have started to give up on oil prices, which means for economic reasons and not for the short run. Maybe, then, it isn’t coincidence many and more of the usual Economists are doing the same though they remain clearly reluctant to do so.

All throughout the past few years, employers have continued to hoard employees even as evidence shows there was little to be gained from it. Maintaining headcounts was mostly about being in position to maximize the future, to be able to pounce on an upturn…should one actually materialize.

This is something I’ve called second-half syndrome, the idea that the second half of whichever year will turn out to be just that time when economic growth finally ignites, validating the labor hoarding and turning around the entire worldwide situation. Why or even how that might happen is never specified because no one ever asks or bothers to think much further about it.

If Jay Powell, Janet Yellen, or Ben Bernanke state there will be a second-half rebound, who would ever argue? Don’t fight the Fed.

When we have seen turning points, however, it’s usually when that rebound fails to show up and, more so, in its place accelerating downside that accelerates to the downside in large part from all the towels being thrown. Which brings us back to Economists as a loose proxy for the bathroom laundry.

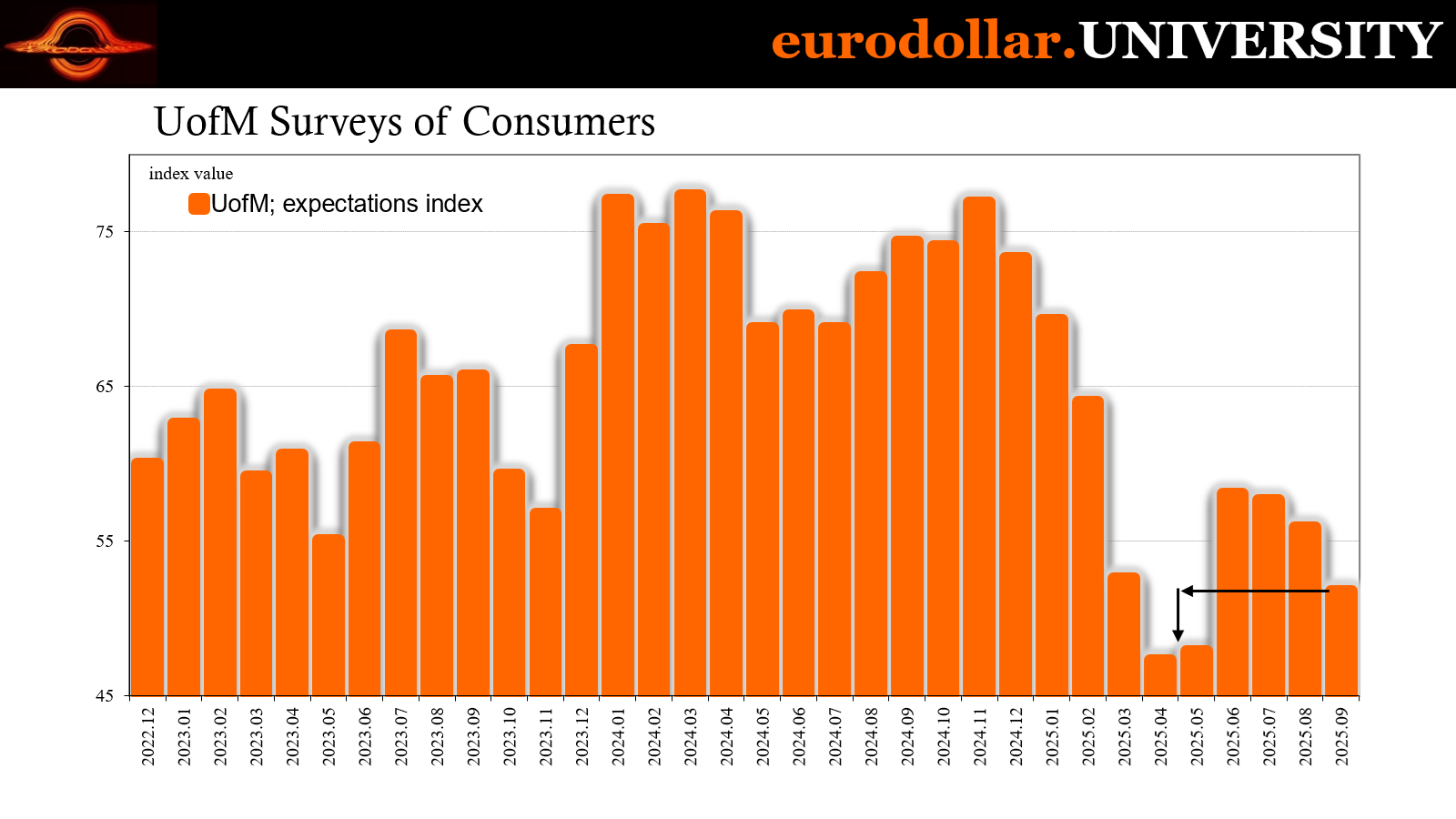

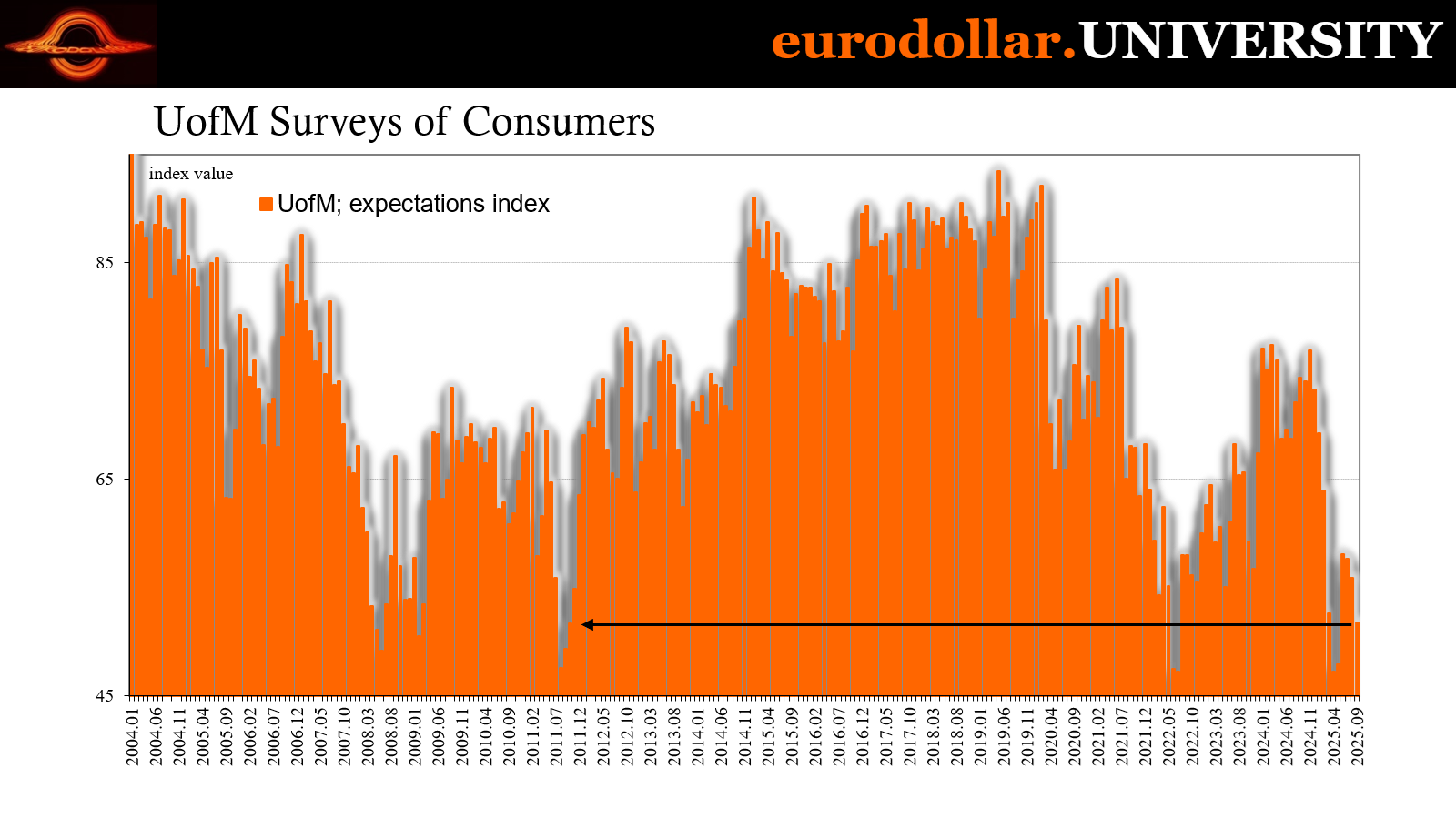

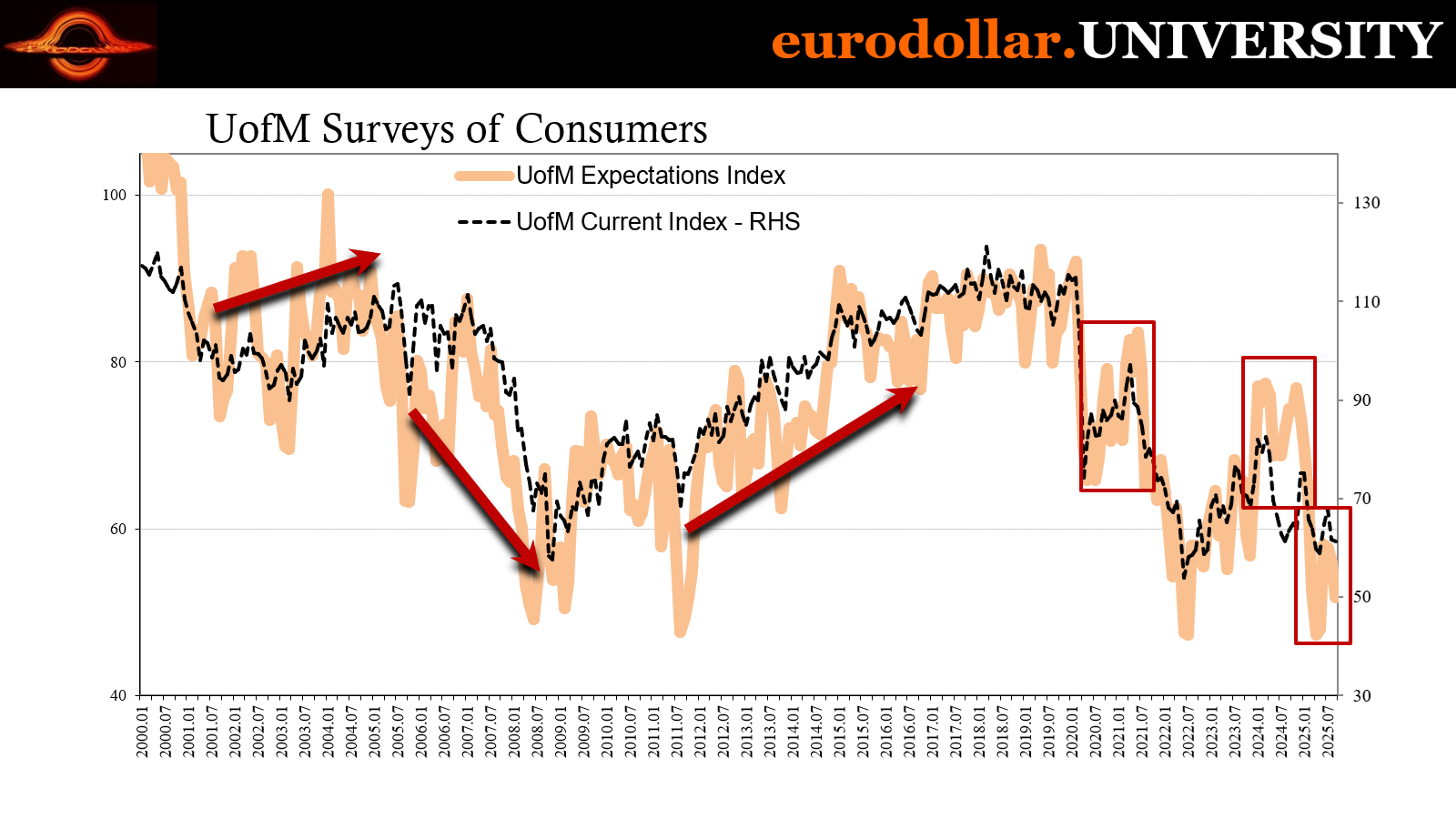

Consumer confidence has been shouting all year about dismal, worsening job prospects only to be ignored. Confidence dropped yet again here for September – despite all-time highs and euphoria in stocks – and is back within just a few small points of April/May lows. There is no mystery as to why that is, expressed by future expectations.

No one was listening to these frustrations before. Now that many are starting to is a signal.

Vibecession vindicated

Most people get their views on the economy from a small few sources. For most, it comes from the media so already a huge mistake since everything expressed by the mainstream is spoon-fed direct from the Fed. The “central bank” has zero incentive to be honest in its assessments; first, because bureaucrats are naturally allergic to admit they’ve been wrong and accepting accountability; second, that CYA is couched in the friendlier-sounding idea how central bankers and Economists have to lie to you for your own good.

If they admitted things weren’t going well, you might take steps to protect yourself and make a bad situation worse, in their view.

That describes the vast majority of the public who have little time to watch closely changes to each and every statistic and so as to individually interpret each macro development. For anyone who does their own homework, they often leave it at a few numbers like GDP, payrolls and the unemployment rate. Again, completely understandable, especially as those accounts are designed for that purpose, to be a quick, handy guide on how everything in the economy might be going.

HOW IT STARTED…

…HOW IT’S GOING

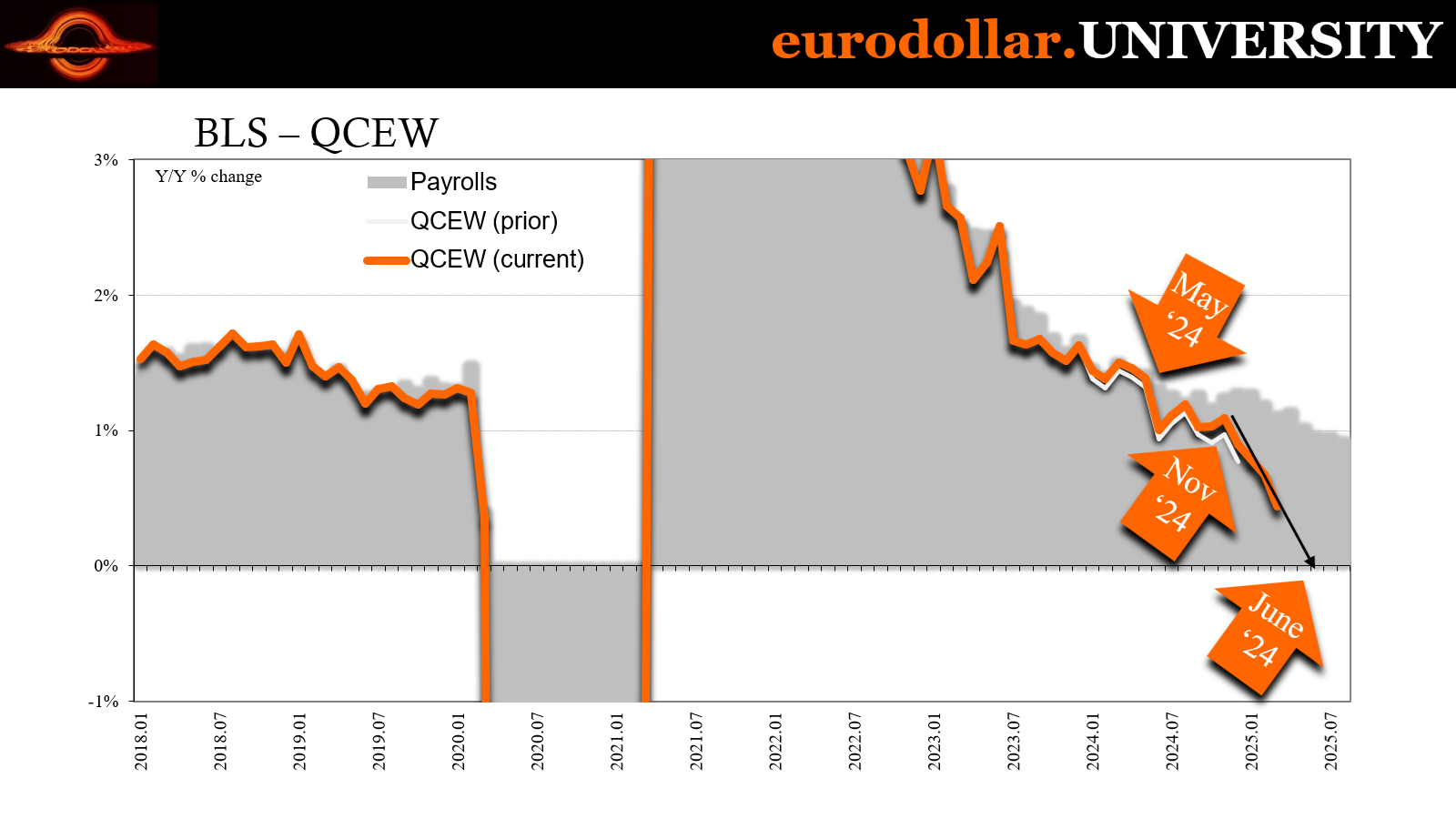

But what if the figures are faulty and unreliable?

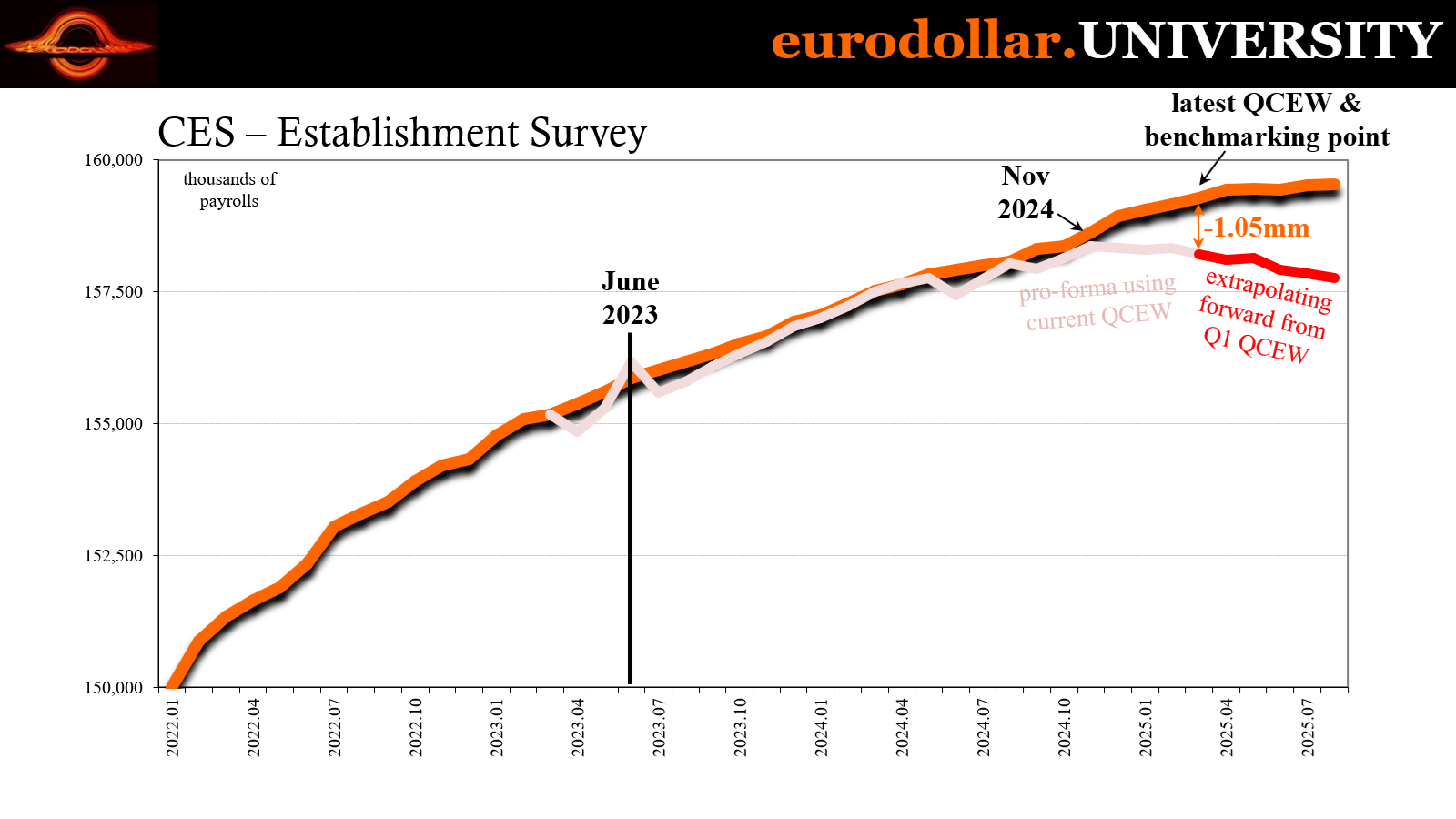

That is where the idea of the “vibecession” came from. Those macroeconomic estimates all seemed relatively solid, stable, maybe even good the past few years (since the banking crisis). Payrolls, in particular, supported the idea of an economy that was strong and resilient, as Fed Chair Powell was once very fond of saying. Yet, the macro data was not matching up with a number of contrary signals, starting, of course, in the broader financial marketplace (not stocks, though the rise in equities was used to try and validate payrolls and the like).

Consumers, too, were not so enamored. They gave off a strong contrary “vibe” no matter how great the mainstream numbers looked any indicated strength wasn’t filtering down to them. I wrote here last August:

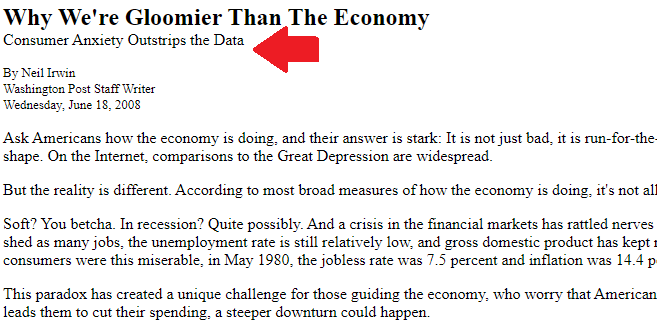

The “vibecession” of 2024 is actually nothing new. During years in which recessions develop, the mainstream media will quite often downplay the risks mainly out of deference to policymakers, particularly those at the Federal Reserve. We’re led to believe the vast stock of PhDs employed by the agency must be useful on all matters tied to the economy, so who would ever disagree with them and their science-y methods?

Bad vibes, therefore, are what consumers or just regular workers and business owners are sensing about how the situation might be developing. In that sense, the debate becomes one between the regular Joes and the econometricians. By the numbers, things look great so it quickly becomes a mystery to figure out why everyone seems to be complaining though doing so without ever considering the most obvious explanation.

Consumers just might be right about the economy even if it isn’t the numbers (yet).

Now it is in the numbers.

The QCEW really hammered this point home. Today, as part of the towel-throwing exercise, the mainstream media (parts of it) confesses, yes, consumers were right all along:

Not that long ago the US economy was wrestling with an interesting problem: jobs data looked very strong with historically low unemployment and historically low firings, but people didn’t feel good about the economy. The dissonance became known as the “vibecession” and was the topic of many economic and policy debates. The question was: Why do people feel bad about the economy when the economy is actually doing great?

Again, hindsight makes it easier, but part of this reckoning should be focused on why anyone truly thought it was doing great to begin with. As I said, there was a bevy of information which directly and far more powerfully contradicted the idea from the very start (being 2022). A huge part of that discrepancy was simply Economists and central bankers as wannabe central planners who outright despise anything associated with a financial market, therefore refuse to consider useful information derived from them (such as turning yield curve shapes into the ridiculous “term premiums” Economists use to transparently avoid having to consider these contrary signals).

The article cited above goes on to add, “With help of revised data, we now know that the vibes were right.”

Consider it a notable towel thrown.

More laundry

The theme during the latter half of this week is mini-waffles. August’s CPI wasn’t disinflationary enough, like the PPI had been, to completely dispel the lingering expectations hawkish policymakers just won’t be able to let go of due to their deep inflationary biases. There was no “tariff inflation”, just more of the “sticky” kind policymakers filter into expectations theory (more Economist nonsense).

We all know just how much FOMC officials can overlook economic weakness for their own shortcomings understanding inflation. We’ve seen it time and again, with 2008 being a prime example. Policymakers during the first stage of the worst deflationary crisis of our lifetimes were more preoccupied by oil prices and how inflationary those would become than they were the constant flood of emails each of them were getting about how Lehman Brothers was going to fail based on the lack of money flow around the eurodollar world.

Oil prices.

In light of that and recent waffle history, it isn’t unreasonable to expect more unreasonable thinking among enough of the FOMC. Even as actual and legitimate evidence continues to pile up for labor market weakness - really serious numbers one after another, too – they can’t help themselves but to focus on the future possibility consumer expectations come unglued and that somehow recreates the entire decade of the 1970s.

It is utter nonsense, but that’s the stock-in-trade for the Federal Reserve. There is a mountain of evidence right now which says the labor market is - at best - in serious danger of sliding into major unemployment, with quite a lot strongly implying this has happened already. On the other side, there remains zero evidence for inflation (especially when taking account of the lunacy in the shelter index), yet we all know there are so many Economists at the Fed who favor the latter anyway.

Being insulated from every consequence gives authorities that luxury. Economists enjoy some of the same detachment, too, however they aren’t entirely free from consequences especially when the tide of data shifts in overwhelming fashion. So, consider a few more towels being tossed around:

Economists at Morgan Stanley and Deutsche Bank accelerated their calls for Federal Reserve interest-rate cuts in the months ahead as slowing inflation and a weakening labor market enable the central bank to quicken the pace of easing.

…

Deutsche Bank on Friday added a third Federal Reserve interest-rate cut to its forecast for the remainder of 2025. The bank previously expected officials led by Chair Jerome Powell would cut this month and then wait to ease again until December. Morgan Stanley economists, meanwhile, now expect the Fed to cut interest rates at four consecutive meetings through January.

The vibes are a vibing the Economists now.

Second half rebound syndrome

Again, the key change we’re seeing is that positive expectations are disappearing along with the notion of a second half rebound. The way it was said at the Fed and elsewhere was that if tariffs didn’t send the world into an immediate tailspin, if we all survived the spring, then things would look up heading into 2026.

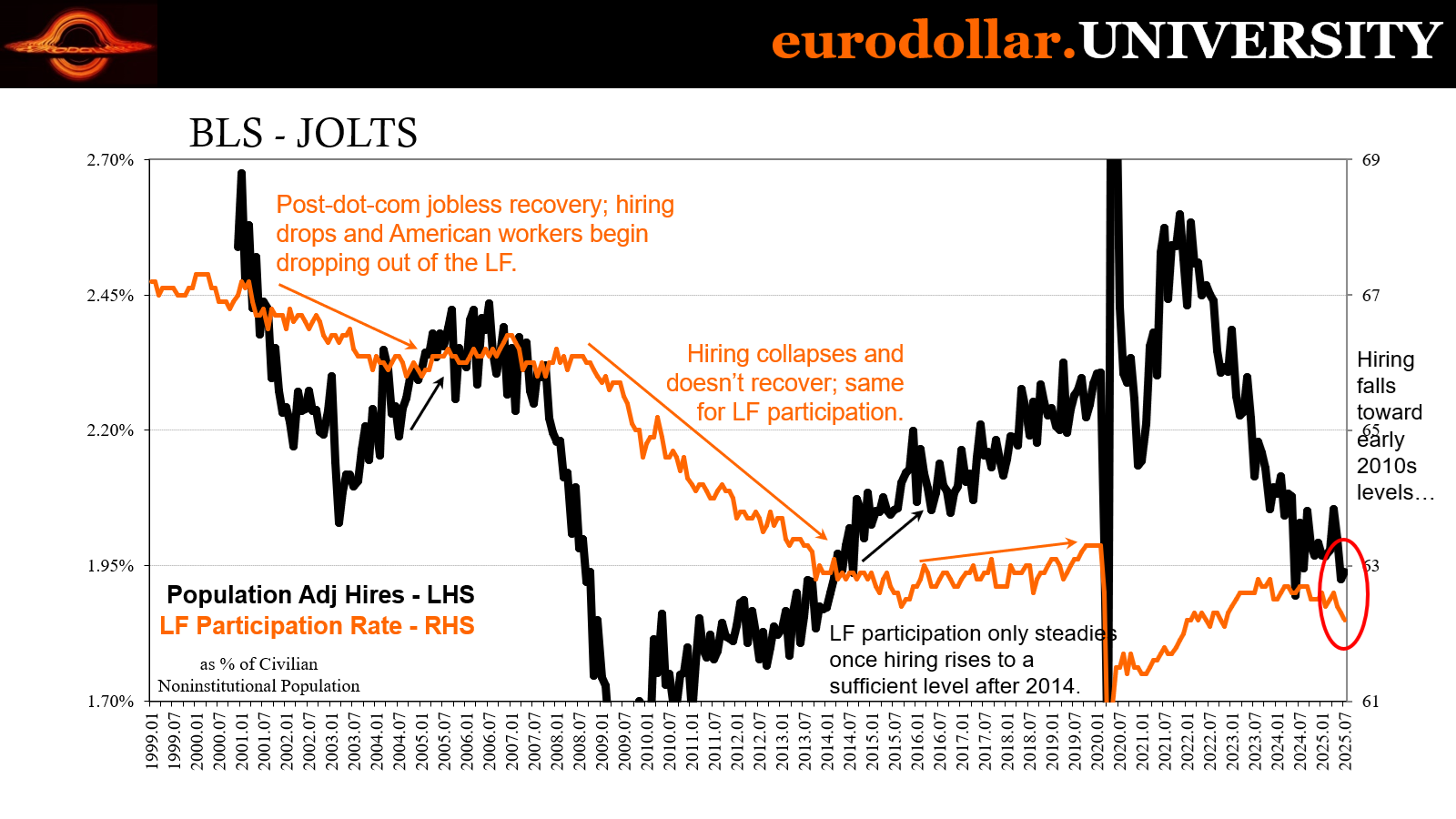

Instead, summertime has proved yet again to be the time for recession. The repercussions are far from being strictly academic. Labor hoarding gets put under scrutiny, as, again, Texas unemployment appears to show.

For initial jobless claims, we’ve seen them bump up at the start of each summer. Though the estimates are seasonally adjusted, they exhibit seasonality anyway (another reason to take a second look at them). What we’re getting instead here from August into September goes beyond a possible seasonal uptick, making it a more compelling notion – especially in this wider context.

SLOWING?

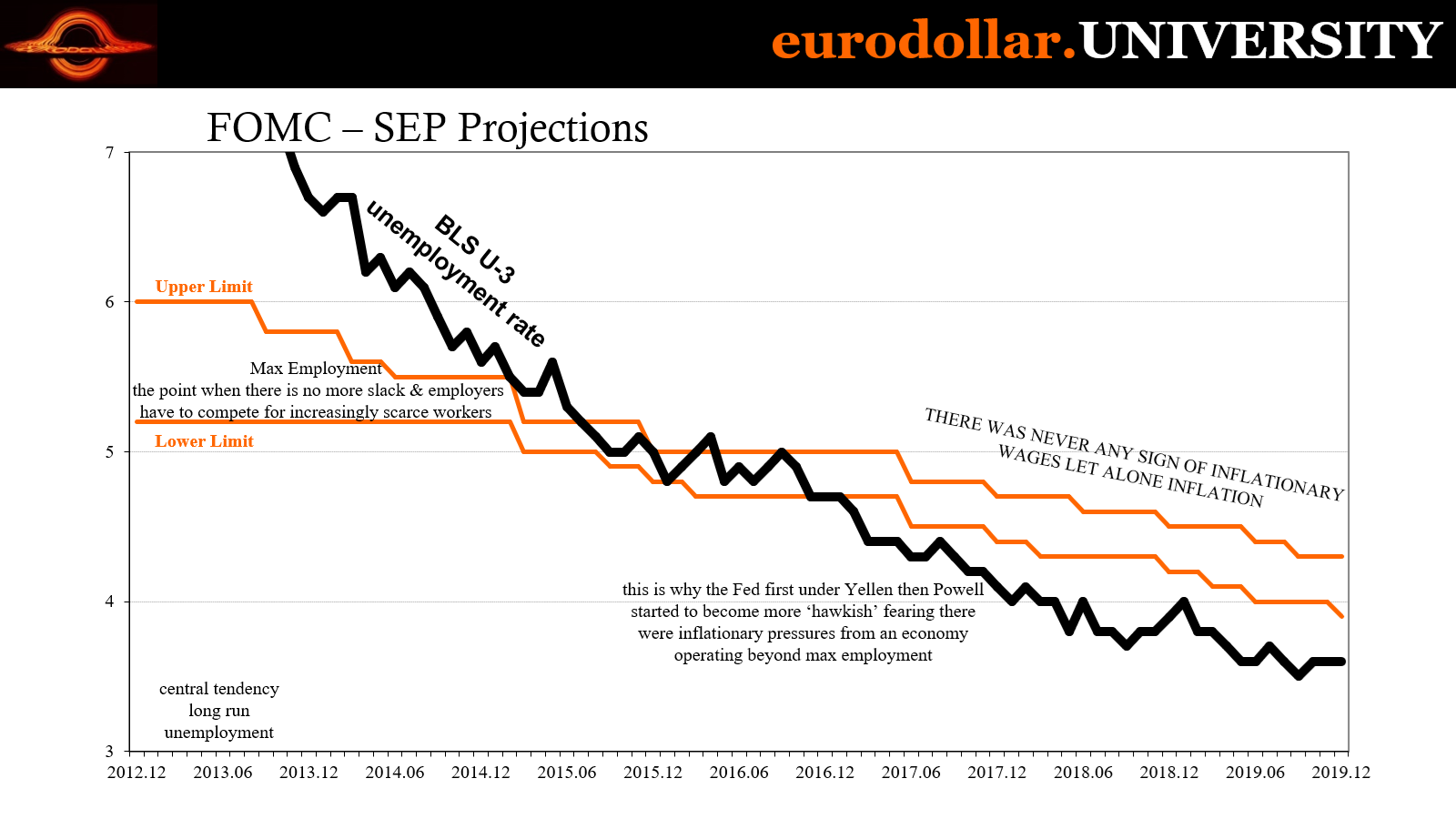

We had been under similar circumstances a decade ago. An oil bust that very nearly put the entire US economy in recession, and it may well have had there been some kind of recovery from the prior contraction in 2008. Companies didn’t lay people off (outside energy) in 2015 and 2016 because they never really hired anyone back to be able to let them go.

Instead, the near-recession of 2015-16 was primarily an extended hiring freeze economy-wide stemming from the failure of a second half rebound in 2015. After blaming low oil prices on a supply glut – there was a glut, but it didn’t show up because unpredictable higher supply did – then-Fed Chair Janet Yellen claimed to Congress the economy would pick up, in part, because lower oil prices act like a tax cut and give consumers more spending power.

Yellen dismissed any negatives, saying, “this sluggishness seems to be the result of transitory factors.” Many Economists had become amateur meteorologists, too, the Fed’s top boss being one herself. In addition to the cold of winter, Ms. Yellen mentioned how there had been a port strike on the West Coast and the always-present “statistical noise.”

Because of what she said were the strong economic fundamentals of the economy, as well as expert central bank policies here and abroad, there was no danger beyond the little bump in the road which started out 2015 on the wrong foot. The second half would bring with it the rebound to cure any ills. Yellen:

As a result, the FOMC expects U.S. GDP growth to strengthen over the remainder of this year and the unemployment rate to decline gradually.

The unemployment rate did continue to decline but only because it was faulty in its own way (participation problem leading to the Fed’s inflation “puzzle” which would vex them right to the end of the 2010s). The rest of 2015, the economy grew worse anyway. It nearly hit a recession starting in Q4, with revised estimates putting the start date in the very same quarter in which Yellen was then testifying.

For every setback and false dawn over the last two decades, each began with what were supposed to have been temporary factors easily overcome by powerful stimulus of all varieties, or the deep inner strength of the economy imposed on it by the incontrovertible support of allegedly monetary masters.

Going back to April 2, 2008, then-Chairman Ben Bernanke went before Congress, too. This wasn’t the regular, semi-annual Humphrey-Hawkins theater. Instead, the Joint Economic Committee was demanding answers. Just two weeks before, Bear Stearns had been shockingly bailed out, shepherded with great assistance from the central bank into the reluctant arms of JP Morgan.

Don’t worry, testified Bernanke. Just passing headwinds.

We expect economic activity to strengthen in the second half of the year, in part as the result of stimulative monetary and fiscal policies; and growth is expected to proceed at or a little above its sustainable pace in 2009, bolstered by a stabilization of housing activity, albeit at low levels, and gradually improving financial conditions.

It was an interesting take, though maybe not for the most obvious reasons. This passage and the sentiment it was built up from illustrated a lot of what continues to plague the global economy.

Central bank policy in particular had come to focus on the aspects of the burgeoning crisis policymakers thought the real trouble underlying everything. As Bernanke said shortly after Bear, they wanted the “stabilization of housing activity.” From that, it was merely expected how everything else including the second half rebound would fall into place. What else could be bothering consumers? Employment?

Housing was expected to be cured by, not making this up, lower interest rates. When it became overwhelmingly clear it wasn’t going to happen, the floodgates were opened up and 2008’s vibecession (it wasn’t called that, but the same thing happens every time) unleashed on everyone.

So, when even Economists start to give up on the idea, that’s not nothing.

Confidence is high in unemployment

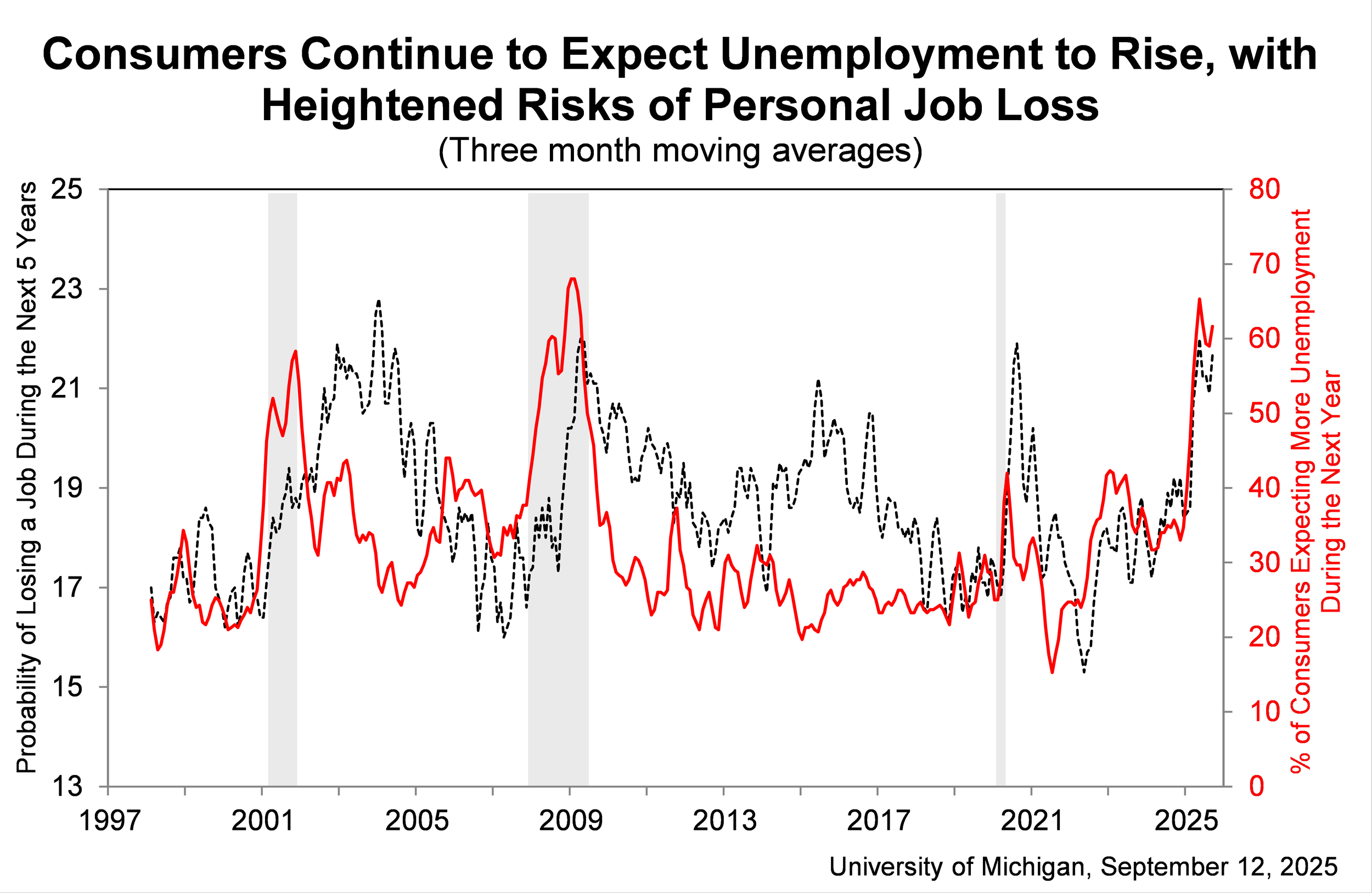

University of Michigan consumer confidence slid “unexpectedly” in September, according to preliminary results from its surveys. That brought the overall index and its expectations component back down a few more points from recent lows – which were at extremes. The reason for this is no mystery, as once again the vibes are all emanating from well-founded fears over unemployment and lost income.

In its press release, UofM noted:

Consumers’ expected probability of personal job loss grew sharply this year and ticked up in September as well, suggesting that consumers are indeed concerned that they may be personally affected by any negative developments in labor markets.

Sentiment like the overall economy was supposed to have rebounded, too. After crashing earlier in the year, overreacting to tariffs, they said, everyone would calm down and with cooler heads the economy would lift off again. That belief is exactly the one driving the herd to pile into equities since April.

CONSUMERS WERE RIGHT ABOUT 2011, TOO

While there was some initial improvement among a few consumers, that’s all being unwound because this summer was devastating to any hope for the second half. It’s not really a question of whether job losses are taking place, it’s how much and then how fast everything might accelerate.

The latter is why, for UofM, job loss expectations remain closer to their highest levels in 2009. Think about that…and then how it isn’t at all out of line with incoming data. In terms of specifically sentiment, FRBNY’s job finding series, for example, plunged to a record low last month, falling by a rate it only recorded during the initial pandemic lockdowns.

There are way too many of these highly unusual developments, which is why the vibe is being taken seriously these days.

Perhaps the most concerning aspect of the Michigan results is looking ahead. Just like market yields and spreads get more negative as confirmation of past badness keeps arriving, consumers like markets are uniform in expecting it gets worse over the next little while. We see that in how low the expectations are compared to the current assessment.

The last time it had been the other way around was the end of 2023 and early 2024. The prospect of lower interest rates combined with growing disinflation had temporarily stimulated some positive forward expectations. It didn’t last, of course, last year’s global inflection showed up and spoiled the positive vibe, spiking job fears and sending future expectations back down because it never was just fears over jobs.

There was a brief resurgence around last year’s Presidential election, but it didn’t last even a month beyond as hopes utterly crashed in December (as job losses likely began to pile up) and have never come back.

As it has turned out, consumers’ “vibe” over the past few years did a far better job of tracking conditions in, and changes to, the actual labor market. They knew employers who had long ago forgotten how to hire were already starting to remember how to fire.

When Economists begin to agree with consumers rather than the other way around, that’s when you really start to know. And that can tell us something important about how thinking might be changing among employers who may have been holding on hoping for the same second half. When even the professional forecasters no longer see it happening, we’re beyond strictly sentiment.