ALL THAT GLITTERS IS DEFLATION

EDU DDA Sept. 2, 2025

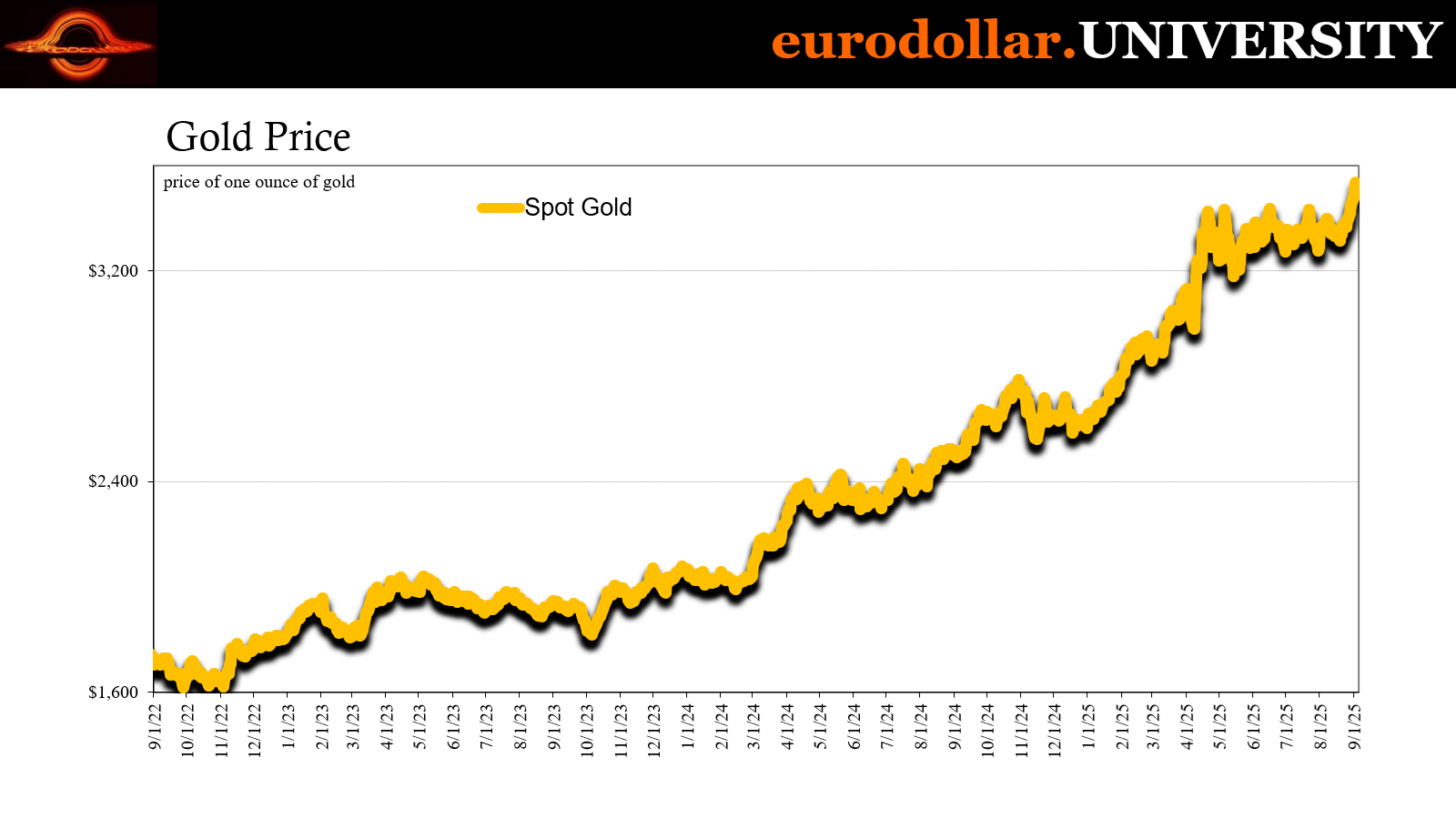

Summary: Gold is finally breaking out, soaring a huge percent today reaching a new all-time high well north of $3500. The reasons why leave it with more upside. Those have nothing whatsoever to do with inflation or a “crashing” dollar. Quite the opposite. From Treasury bill yields to term SOFR, on the macro side with ISM, construction and consumer spending on services, the evidence for a flat Beveridge keeps getting bigger and that is what’s propelling gold. The fact bullion is massively illiquid just makes an even more robust signal.

BULLION IS GLITTERING TODAY, AND THAT’S REALLY TOO BAD.

As the US returns from its Labor Day holiday, gold is – by far – the big winner from it. Stress in the US labor market, how fitting, has the Federal Reserve more than leaning back into the Pringles can. Markets are pricing more confidently the FOMC, led by lame duck Chair Powell, will not be able to chicken out. This week will have the JOLTS estimates (tomorrow), ADP, jobless claims, finally August payrolls and employment (or unemployment) come Friday.

Following those, next Tuesday returns the QCEW with its Q1 2025 estimates plus the preliminary benchmark revision to CES payrolls. The next week will be a busy one where it comes to labor data. In the meantime, we have a growing number of signals for our Beveridge search.

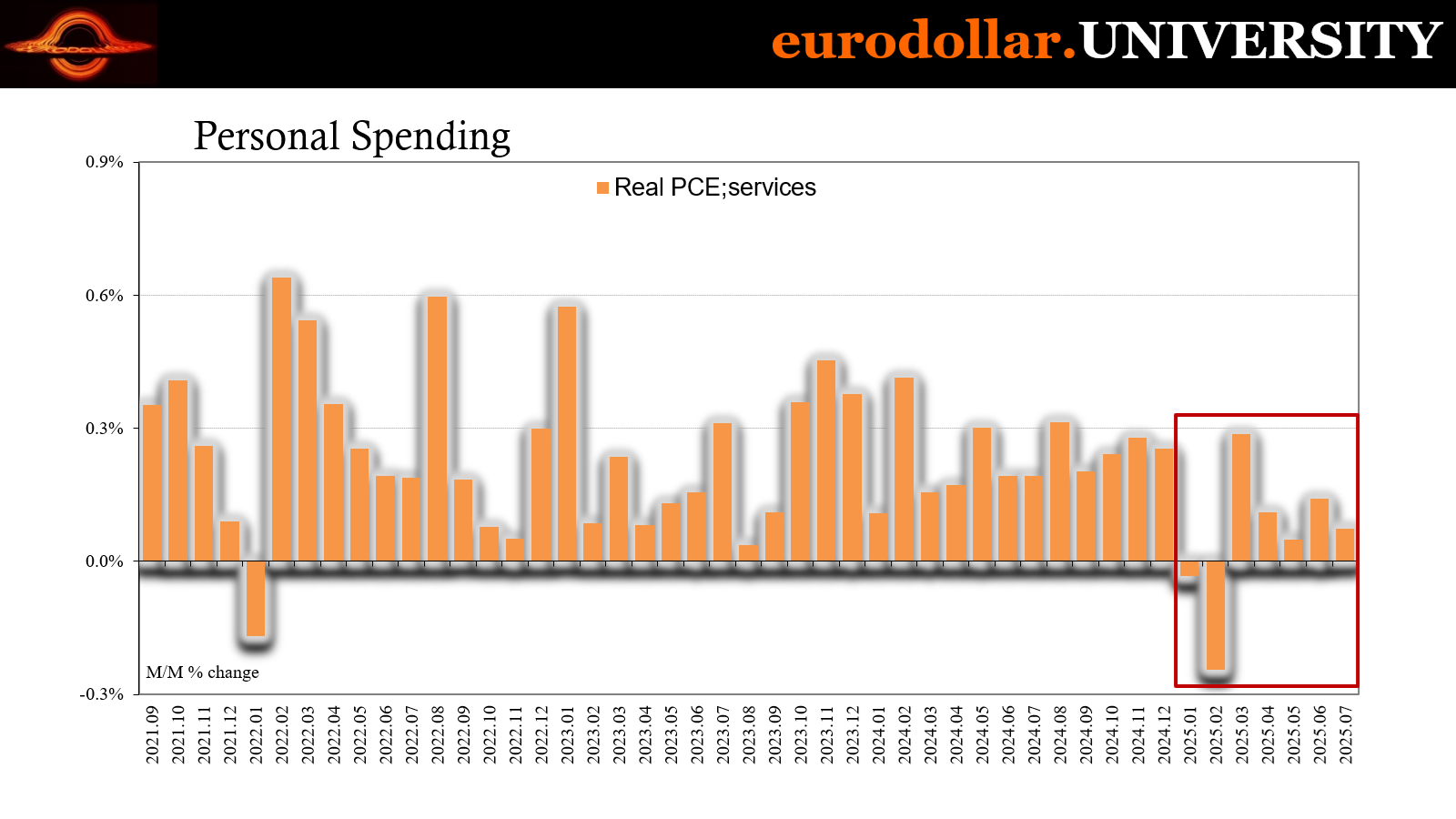

Last week’s Personal Income stats and more so Personal Spending align with the labor market trouble driving the FOMC toward Pringles. Even though spending was better overall on the month, it was not in services showing again the crucial change in consumer behavior. Today further brought ISM’s indexes plus Census’ construction spending figures, both of which reinforce our perceptions, and gold’s, about why consumers have shifted this year.

With another helping of Pringles on deck, it has helped propel gold out of its multi-month rangebound trading. Bullion had been stuck around $3350 to $3400, back and forth ever since its last record high in April. That was already a critical signal since the metal refused to give any of that back even as stocks soared and re-risking found some substantial appetite in credit.

As of today, it was gold’s turn to soar, pricing not just above $3500 per ounce but getting all the way to $3530 and better. There remain many parts of the mainstream which wrongly conflate that sharp return with inflation perceptions when the driving force behind the all-time highs is the total opposite. This is not mere conjecture on my part, no matter how much you will continue to hear otherwise from the unaware or unwise mainstream.

This is all the more remarkable once you realize how little use gold has in any monetary sense (as I’ll describe).

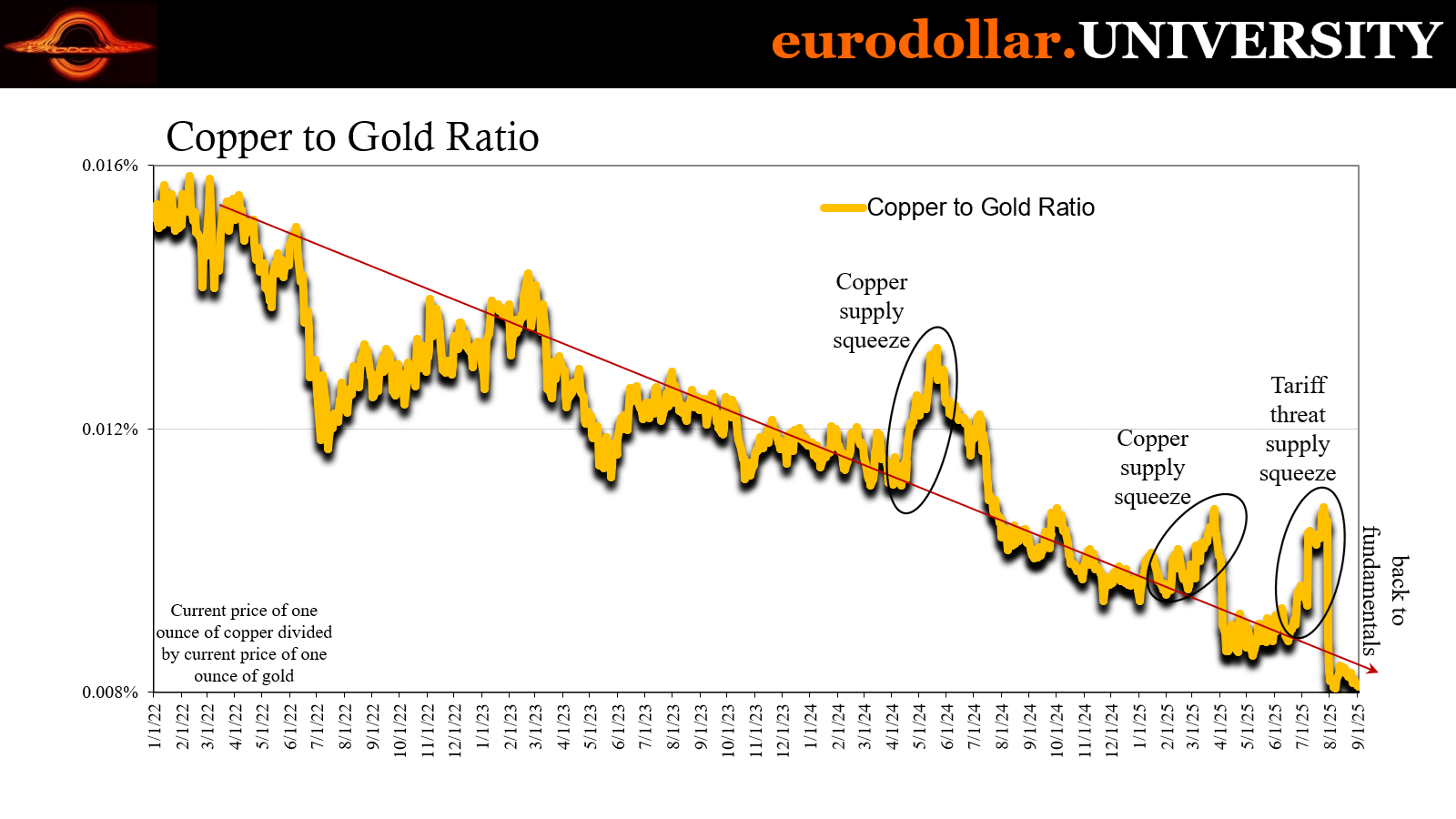

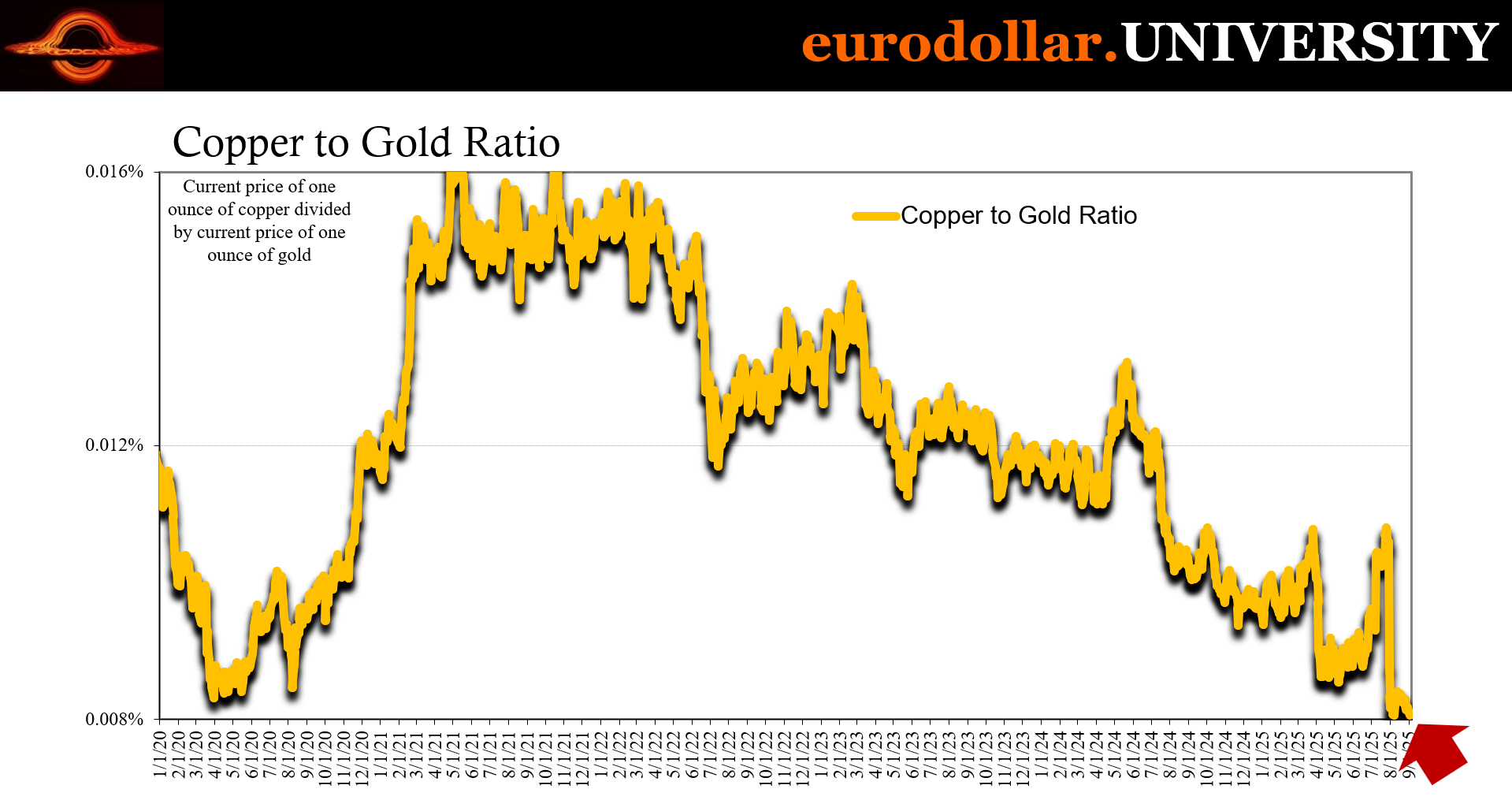

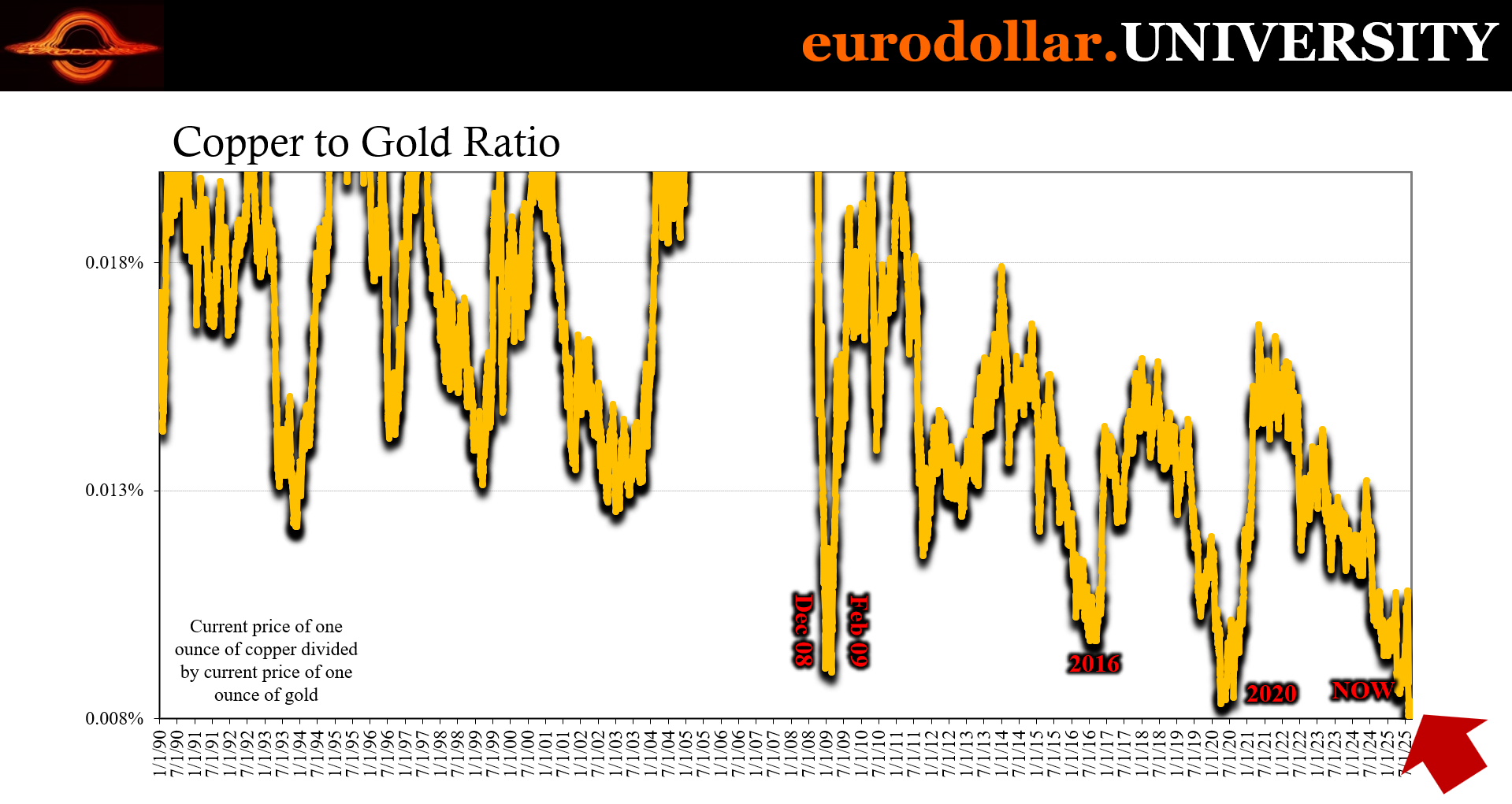

If there were any lingering doubts, the copper-to-gold ratio was left a few hundred-thousandths of a percentage point above its multi-decade low set about a month ago on August 7 in the aftermath of the July payroll numbers. Altogether, not a fleck of an inflation hint anywhere, though tons, too many to the opposite.

De-monetized has technical meaning

Gold is no longer money nor is it all that liquid. That makes its rise during generally deflationary perceptions even more extraordinary knowing how, if push comes to shove and money/collateral circulation dries up, anyone holding bullion will be left with an asset difficult to sell in order to obtain some media that is useful (meaning eurodollars). This makes it less attractive to own among the highly-leveraged, thus already a clue behind the demand for it.

Though the metal had been demonetized by the “great” events in 20th Century history, the metal remains a modest fixture attached to the 21st Century’s complicated international infrastructure. It has a role, but to do what, exactly?

In treating bullion as an asset, it is a number on a reported balance sheet, an avatar of some quantity of Element 79 sitting in a room somewhere. It has a current value for that amount, yet store of value aside its use as an effective medium of exchange is no longer anywhere close to actual exchange.

For example, in December 2009 and January 2010, the BIS found itself at the center of weird controversy when it abruptly but quietly reported a $9 billion (give or take) gold swap. Uncovered by some enterprising reporting (back when that was a thing) at the Wall Street Journal digging through its arcane financial statements, several hundred tons of bullion had been temporarily exchanged for US dollar credits.

I wrote about it many years ago, back in April 2013:

Subsequent investigation by media outlets, including the Financial Times, reported that the BIS had indeed swapped in 346 tons of gold holdings from ten European commercial banks. That was highly unusual in that gold swaps are typically conducted between and among central banks. Included in that list of commercial banks were, according to the Financial Times, HSBC, BNP Paribas and Société Générale. The timing of the swaps was pinned down to sometime between December 2009 and January 2010 - just as the world was getting reacquainted with the Greek Republic.

Greek bonds, largely European banks desperate for dollars, and the BIS covertly bailing them out (as is its mission) with gold the centerpiece security to the international agency’s rescue plans.

In other words, these banks had been hit by an “unexpected” collateral shortage due primarily to the haircut re-assessments made by collateralized markets (repo) on weaker sovereign credits previously stood up as pristine.

If you were BNP or any other drawn into the maelstrom from having borrowed $100 “cash” (book entry) from the global eurodollar market collateralized by, say, $110 in Portuguese or Italian governments (also book entry), then as Greek bonds lost value (for obvious reasons) that spilled over into these others which caused cash US$ lenders to revalue their collateral haircuts to something a lot less than $110.

In this situation, either the borrower is only able to borrow a lot less based on the lower collateral value (higher haircut), or it suffers a potentially catastrophic drop in liquid funding requiring a whole bunch of painful, possibly dangerous downstream propositions (such as fire-sales of assets likely producing accounting losses; see: SVB).

However, these European banks had been “gifted” a lifeline by unsuspecting regular Europeans who had only been interested in buying and holding physical gold in the years leading up to late 2009. Basically, these bank customers purchased the custodial services from particular banks at which to store actual metal bars, but to save on custodial costs those bars were held in unallocated accounts.

This had meant the banks’ legal obligation as custodian merely involved making sure that, on demand, it would release the same quantity of physical metal to its owner; though not the same exact metal bars put on deposit originally.

Gold had become a liability of the custodian which further allowed, in times of trouble, the gold owned by its customers could be used for the banks’ individual purposes. As a historically-valued safeguard, even if demonetized, it was usable as fungible collateral of last resort (infuriating classical gold standard enthusiasts ever-more).

The problem was size. What I mean should be obvious; a massive dollar funding shortfall as a result of massive haircut adjustments (including on any collateral transformations in securities lending arrangements) would require so much gold to pledge that only a few counterparties could ever hope to efficiently process the whole swap.

Enter the BIS. It had the facilities (not necessarily physical, more so accounting and legal; again, book entries of ledger money) to facilitate that amount in swaps with those major banks. Not only could it handle the gold (book entry) coming in, it had access to US$ (book entry) cash already on its books.

All it required was motivation. Crisis will do that.

Upshot

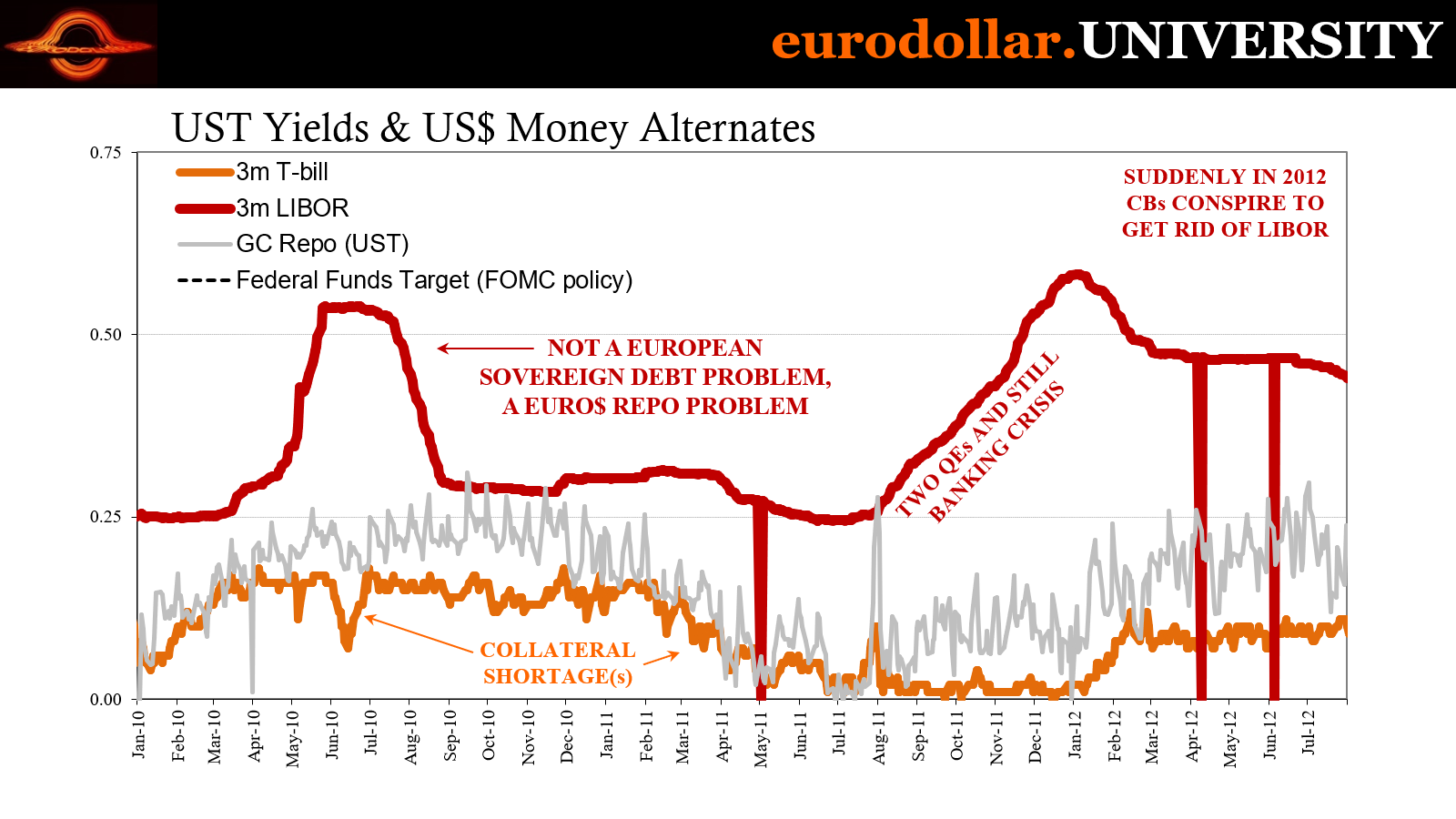

That didn’t last, however, because as the global eurodollar situation only worsened throughout the rest of 2010 (the Fed’s QE2 didn’t even make a dent) on into a subsequent full-blown global crisis in the middle of the following year. By late 2011, this gold-as-collateral-of-last-resort wasn’t finding any private takers.

Not for lack of trying, either. Several media outlets, in light of 2010’s BIS activities, had kept an eye on this otherwise little-noticed corner of the money (book entry) marketplace. As the 2011 funding and collateral crisis deepened (Euro$ #2), what the newspapers reported wasn’t good.

On November 30, 2011, for example, the Financial Times had described how, “...few, if any, banks were likely to receive the published rates since they have been skewed in recent months by a widespread reluctance among bullion banks to take gold for dollars." This despite the fact the Federal Reserve, in quiet, uncomfortable response to this second dollar funding crisis, had restarted its already-failed (2007-09) overseas dollar swap program barely two months prior to this report.

There were no eurodollar takers in the market for the gold collateral, and, apparently, no additional BIS support given the politics of the situation had changed remarkably since January 2010 (any perceived “bail outs” had become a toxic policy, even if nothing more than a harmless proposed repo with gold as collateral). Within days, by December 8, 2011, rumors persisted that one possibly two major European banks had been brought to the brink.

European banks suffered greatly, as did many counterparts around the rest of the world when this dollar funding chaos provoked widespread economic as well as financial pain in far-flung locales nowhere near Europe (see: Jinping, Xi). In many crucial aspects, the global system has never been able to recover from this second devastating blow.

So, why didn’t any of them who had access to unencumbered, unallocated gold just off and liquidate what they had? After all, their obligation was only to ensure gold would be available to their customers upon demand; sell in the emergency and buy it back later when out from under it.

The answer is just as simple as it may be eye-opening. You can’t just sell 346 tons of gold all at once. Gold is, in its demonetized state, one of the most illiquid assets on the planet. It is nice (when the price is up) as a number to report on some kind of statement, such as an IMF template, a store of value kind of feature, but as a useful medium especially in times of currency privation, its useful “value” isn’t close to what it is printed on the call sheets.

Just ask those stranded Europeans, along with an unnamed and undiscovered more.

Why would banks and CBs buy so much gold?

Gold has a place as a reserve asset, just not a liquid one. It is effectively store of value alone, therefore inappropriate as a standalone. This is where Treasuries and especially bills are supreme. Bullion has close to zero moneyness whereas a bill has roughly the same as (if not better than) cash. Yes, better (see: bank reserves).

If a local bank gets into dollar funding trouble, mobilizing gold is cumbersome, inefficient and unpredictable. As with the above European example, try to sell half a thousand tons on a moment’s notice and see how it goes or what price clears the full lot.

That means those who are turning to gold as a hedge are almost certainly official types as well as general financial institutions with other more liquid reserves assts and either no leverage (meaning rollover funding risk) or not enough that would force liquidation (as in 2010-11). An illiquid deflation hedge!

Instead, the value comes from opportunity and, yes, that very deflation. The general marketplace (ex-leveraged funds) is far more likely to seek gold during those times as a hedge against some of the worst cases. And since those relative worst cases (not necessarily a crisis) will almost surely bring ultra-low interest rates that stay ultra-low for a long time with them, there’s little opportunity cost to owning the hedge.

Thus, gold has nothing whatsoever to do with inflation. It was only that way in the one specific instance of the out-of-control eurodollar back during the 1970s. Apart from that, over the last twenty years since gold really got going in the middle of 2005, demand as a hedge has been entirely against deflation and, in particular, its long-term consequences.

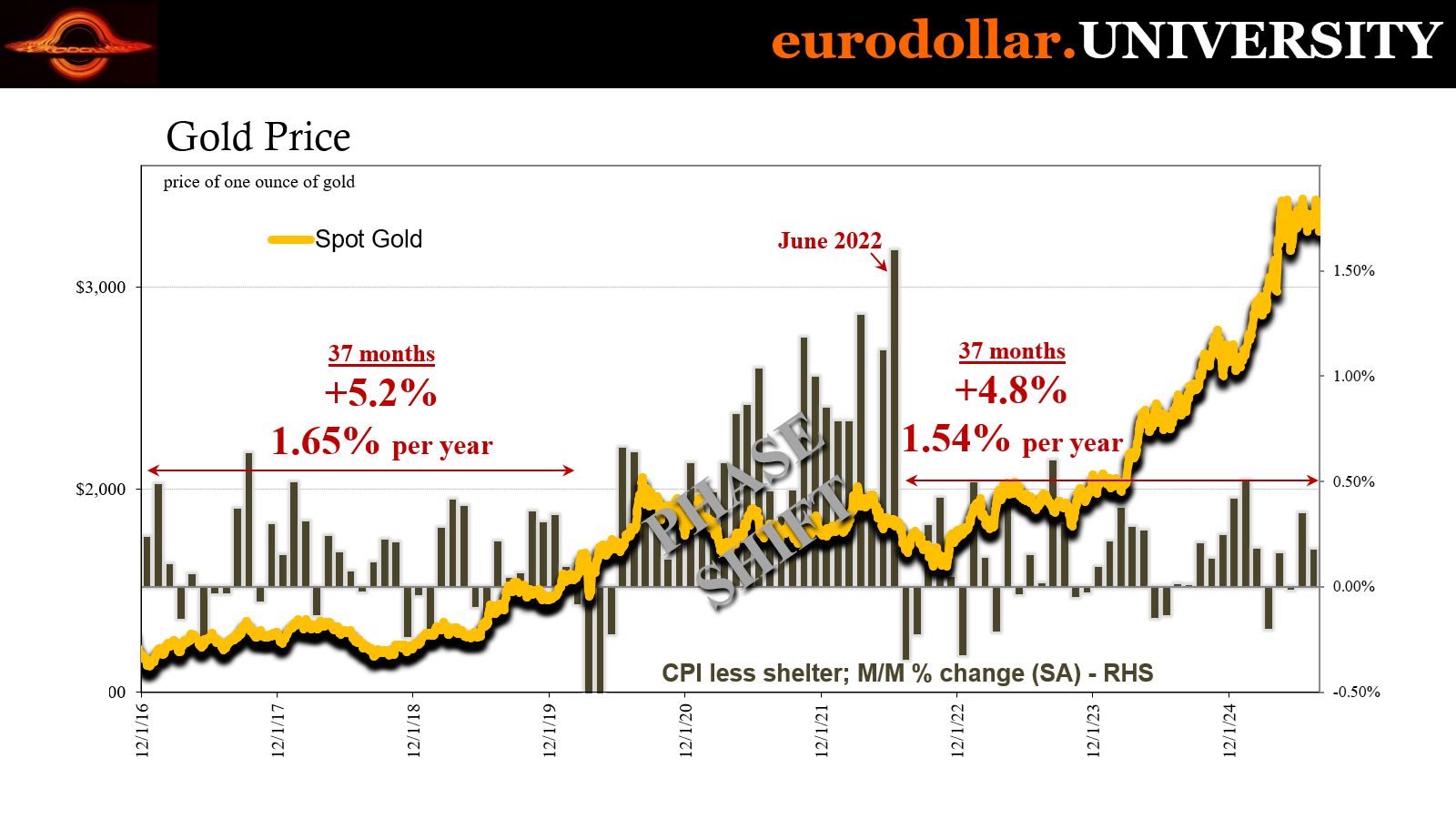

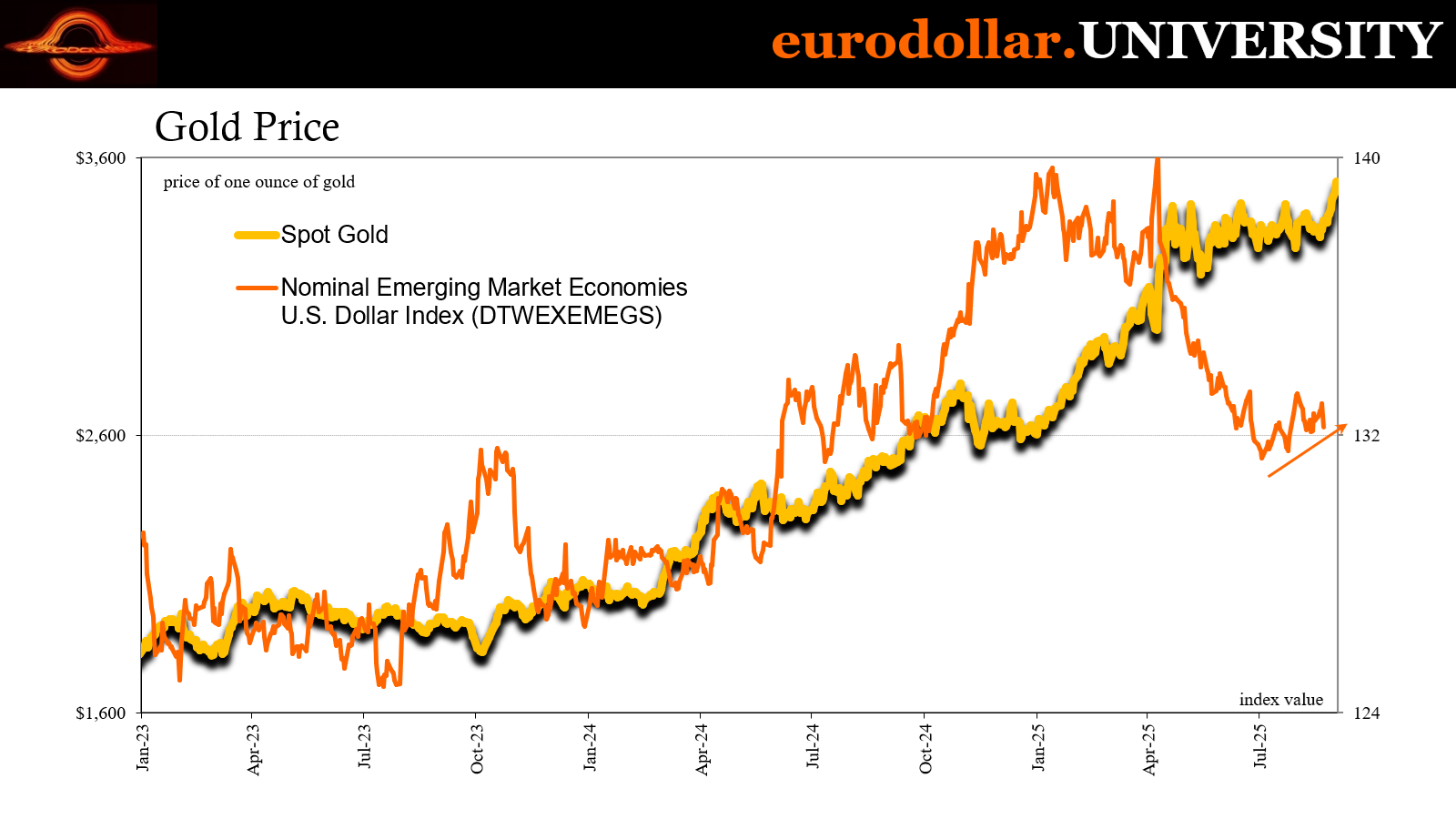

And, yes, this extends all the way into the 2020s. You only need to see the price of gold matched against the CPI to see what exactly I mean (or against the US dollar exchange value, even faulty DXY). Gold was rising sharply from the middle of 2018 back when the already-disinflationary 2010s were about to get even more so.

Even as the dollar was sent soaring by Urjit Patel’s “dollar funding has evaporated”, those very deflationary circumstances triggered enormous buying of bullion for the rest of that year and right on through 2019 into pandemic-riddled 2020. Again, gold like the dollar soared during the deflationary bits even if the mainstream will still try to wrongly convince you gold goes up when the dollar goes down.

Totally false.

FINAL PROOF: GOLD ROSE DURING DISINFLATION (DEFLATIONARY CIRCUMSTANCES) BUT FELL DURING WHAT EVERYONE THOUGTH WAS INFLATION.

But once “inflation” turned up around the middle of 2020, the whole marketplace turned away from gold. No one was seeking bullion right when the CPI was soaring at its seemingly 70s most. For what everyone says is an inflation hedge, when “inflation” was at its absolute worst in living memory, gold demand sunk along with its price.

Terrible inflation hedge.

For one, it was never inflation and the gold market understood that critical difference. Instead, the lack of interest in gold was partly higher interest to come from the market for hedge alternatives like Treasuries, but also because that period was broadly seen as reflationary. For a few months, maybe even a year up to the middle of 2022, the global system appeared like it might actually escape the pandemic lockdowns with manageable damage.

Thus, less demand for the end-of-world hedge when the world seemed as though it could possibly get back on track.

GOLD HAS BEEN SIDEWAYS SINCE APRIL AS THE DOLLAR EXCHANGE VALUE HAS RETRACED OFF ITS EXTREMES; ONCE THE DOLLAR STARTED TO RISE AGAIN, NOW RATES ARE GOING DOWN AND GOLD HAS BROKE OUT OF ITS RANGE…

But once it became clear that wasn’t going to happen, gold started to come back into the picture. Consumer price pressures (the phase shift) were already over with by then, only further emphasizing the nature of the situation – forgot how to grow. And in a forgot-how-to-grow world, that meant no inflation plus no further “inflation” (supply shock), slowing and reversing economic fortunes due to widespread impoverishment and the hit to employment potential, all of which would eventually lead to lower interest rates for the long run.

The latter is why gold began to surge starting in October 2023 – coincident to the bond rally. Again, deflation potential drives gold, a rising dollar world rather than inflation and “sell America.”

And if there was any remaining doubt, which there really shouldn’t be, again take a gander at the unambiguously deflationary depths the copper-to-gold ratio has sunk to.

In with gold, markets and macro

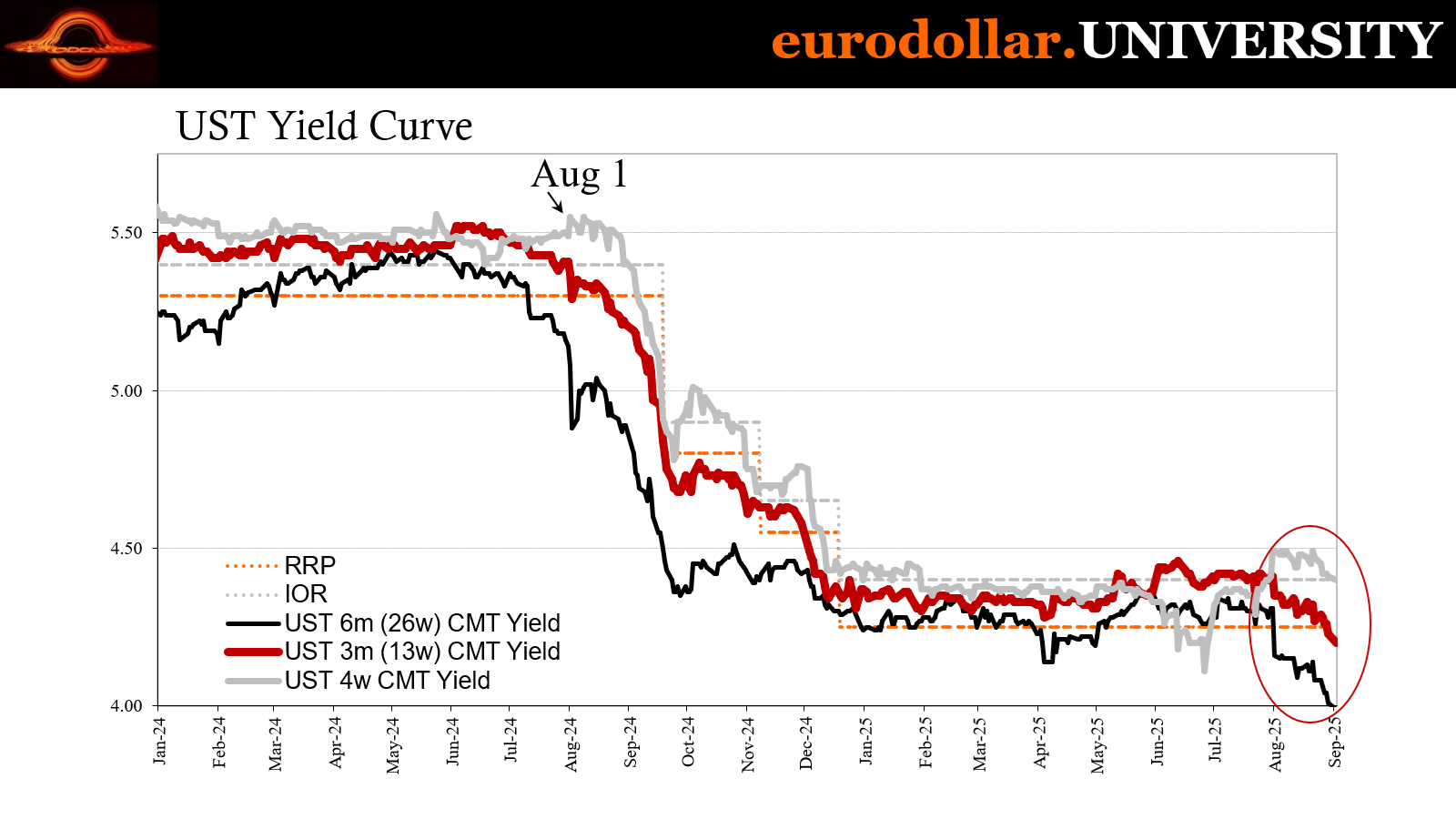

Treasury bill yields and various other market rates are hitting new benchmarks, though I mean in the informal sense. The 6-month bill dropped below 4.00% (according to the Treasury Department’s calculations of its investment rate) while the 3-month maturity slid to 4.20% for the first time in years.

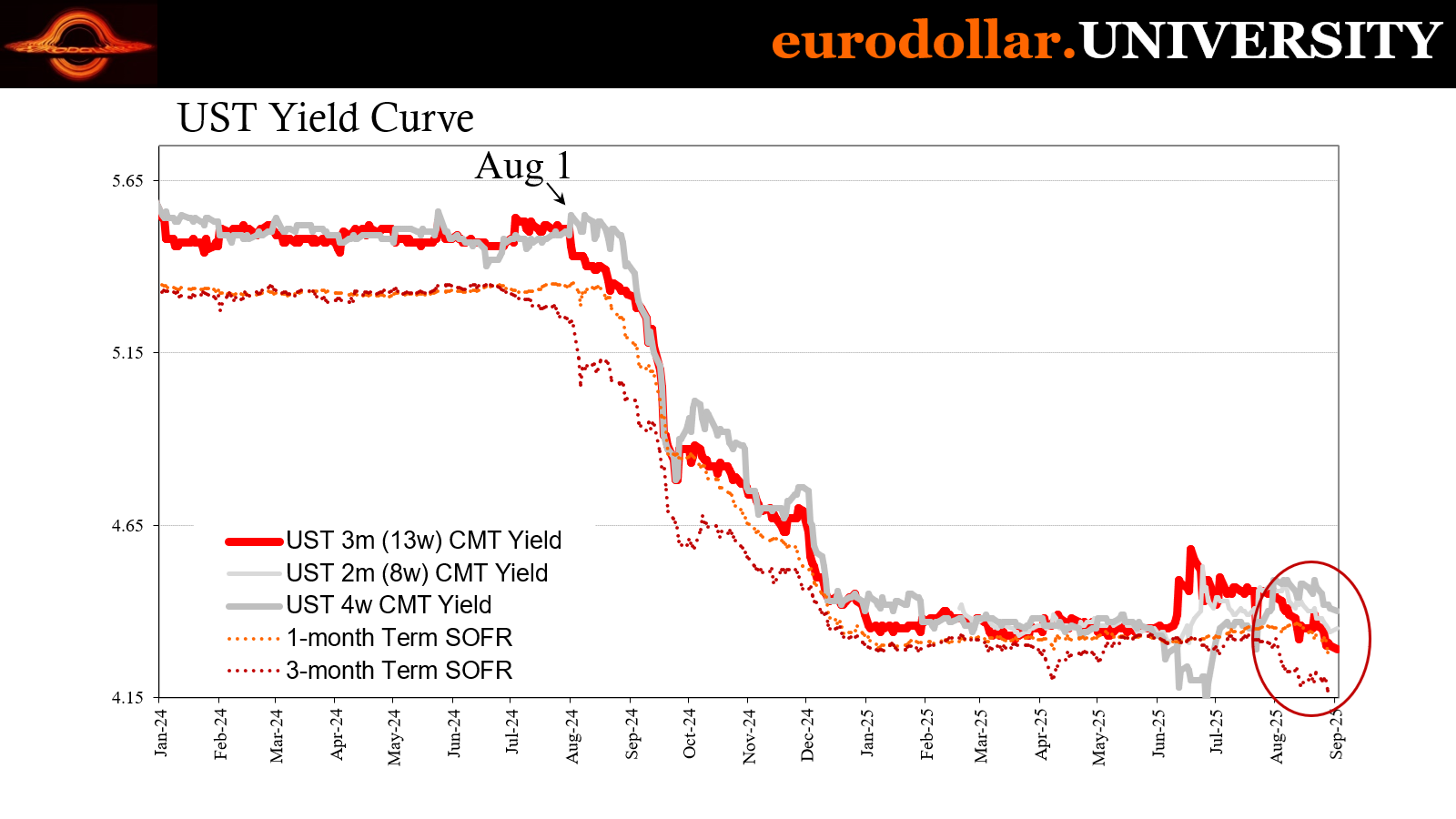

Alongside bills, term SOFR rates (these are what are supposed to substitute for term LIBOR rates; the 3-month term SOFR estimate is derived from term SOFR futures as an approximation for what 3-month LIBOR used to be, when term SOFR is definitely not that) have begun to shift, too. The 3m rate fell to 4.17% and even the 1m rate has dropped by roughly nine basis points going back to mid-August – not coincidentally the same timeframe as when gold began its current breakout.

It's not that falling bill and term rates are driving the metal’s price, rather what those represent in a growing probability the FOMC doesn’t chicken out and pause any longer, plus the rising coincident chances the rate cut in September is just the beginning in the next series of Fed action getting the policy benchmarks far closer to that long run future of a lot lower rates for a lot longer.

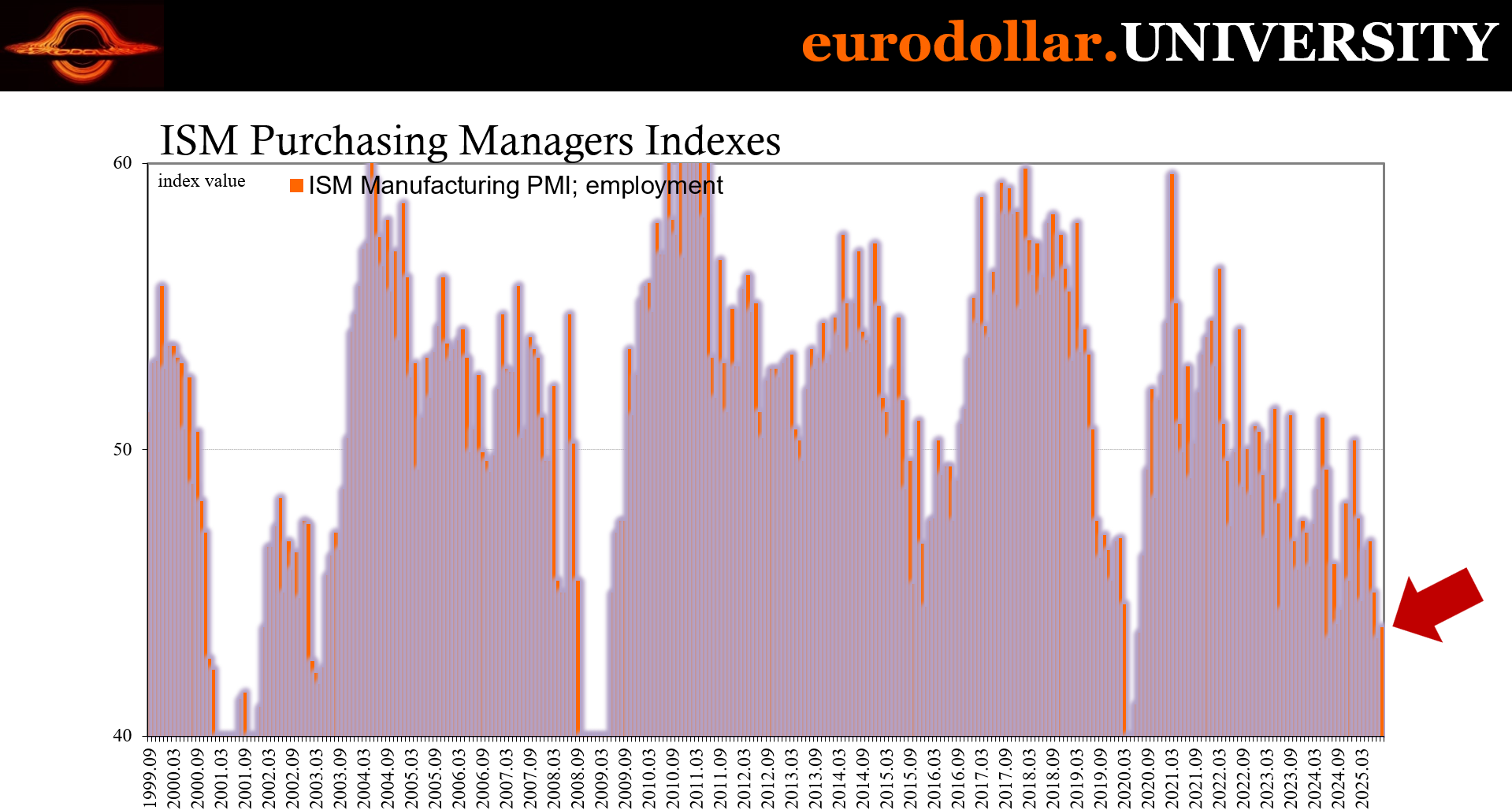

The macro reasons for this are naturally consistent with soaring gold, too; those being increasing signs from all over the economy pointing to a potential if not ongoing shift in employment along the flat part of the Beveridge Curve toward unemployment.

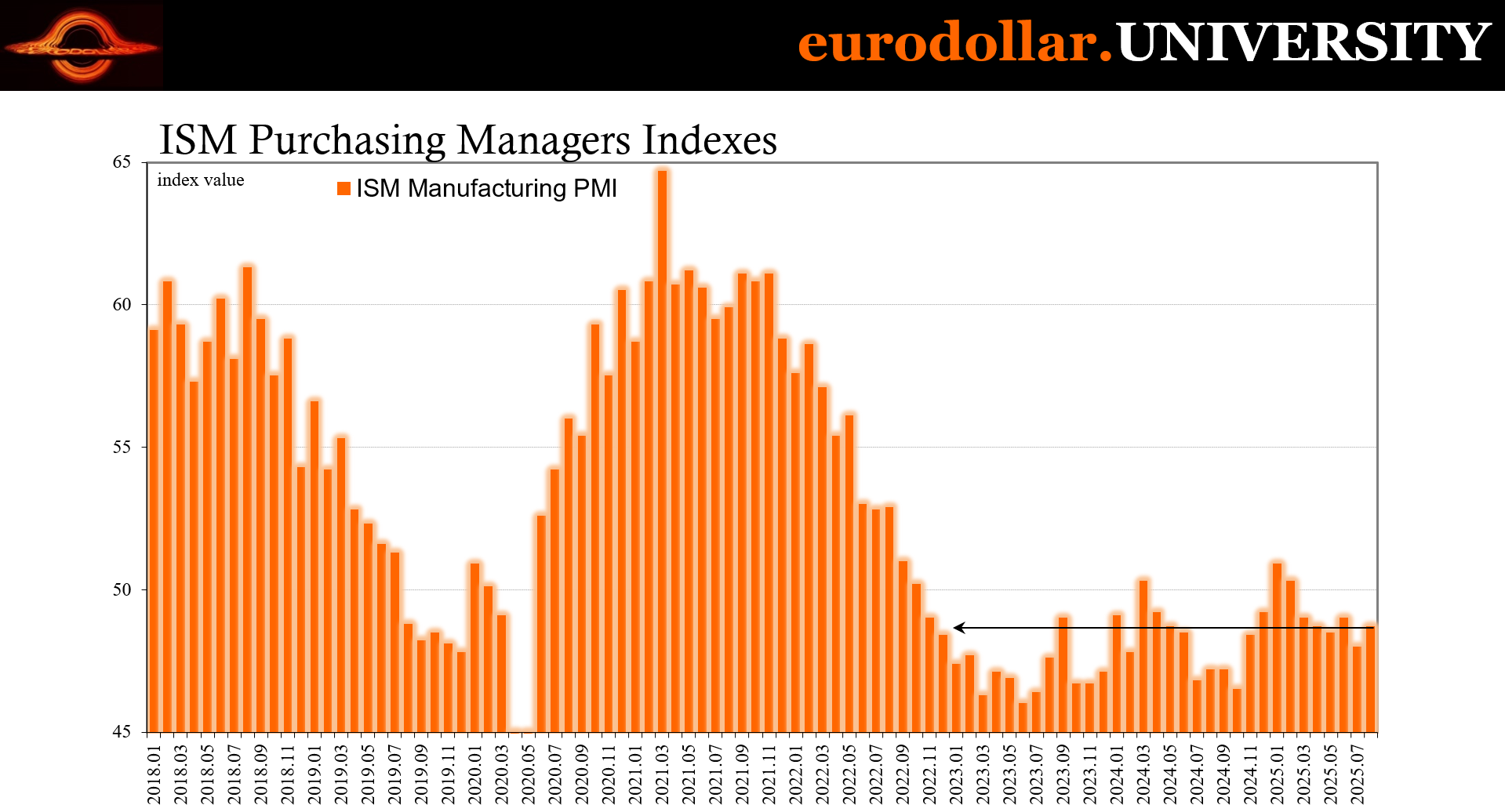

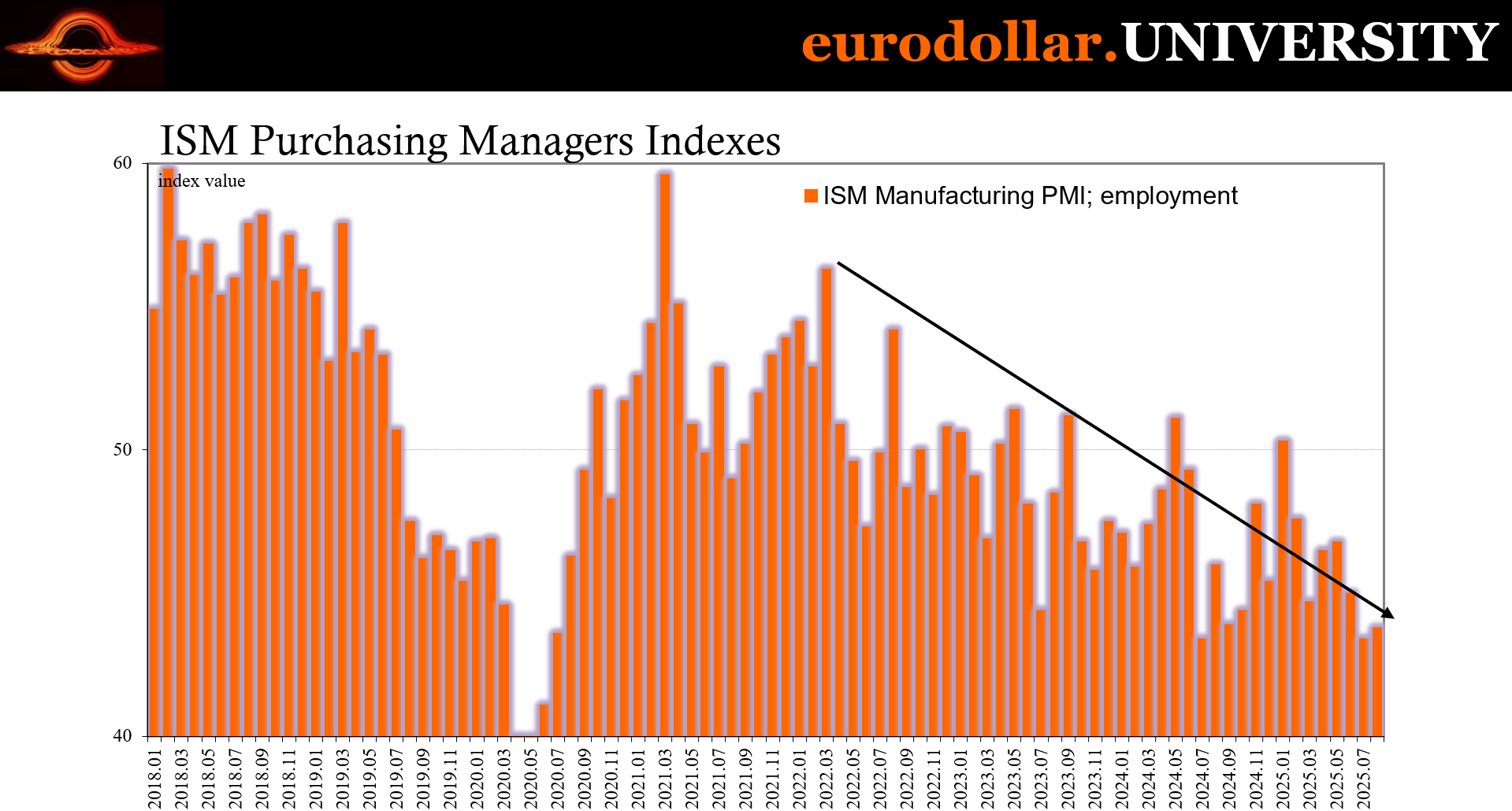

Among the data released today doing this, ISM’s manufacturing index and construction spending. With the former, while the overall PMI managed a small gain, its employment measure remained significantly below fifty and basically unchanged from July. At barely more than 43, this indicates sustained employment problems among producers even as they churn out as much as they can for inventories.

Being squeezed by rising cost pressures and limited overall demand, employees are going to be caught in that crossfire which is one of the major factors which would drive the push along Beveridge.

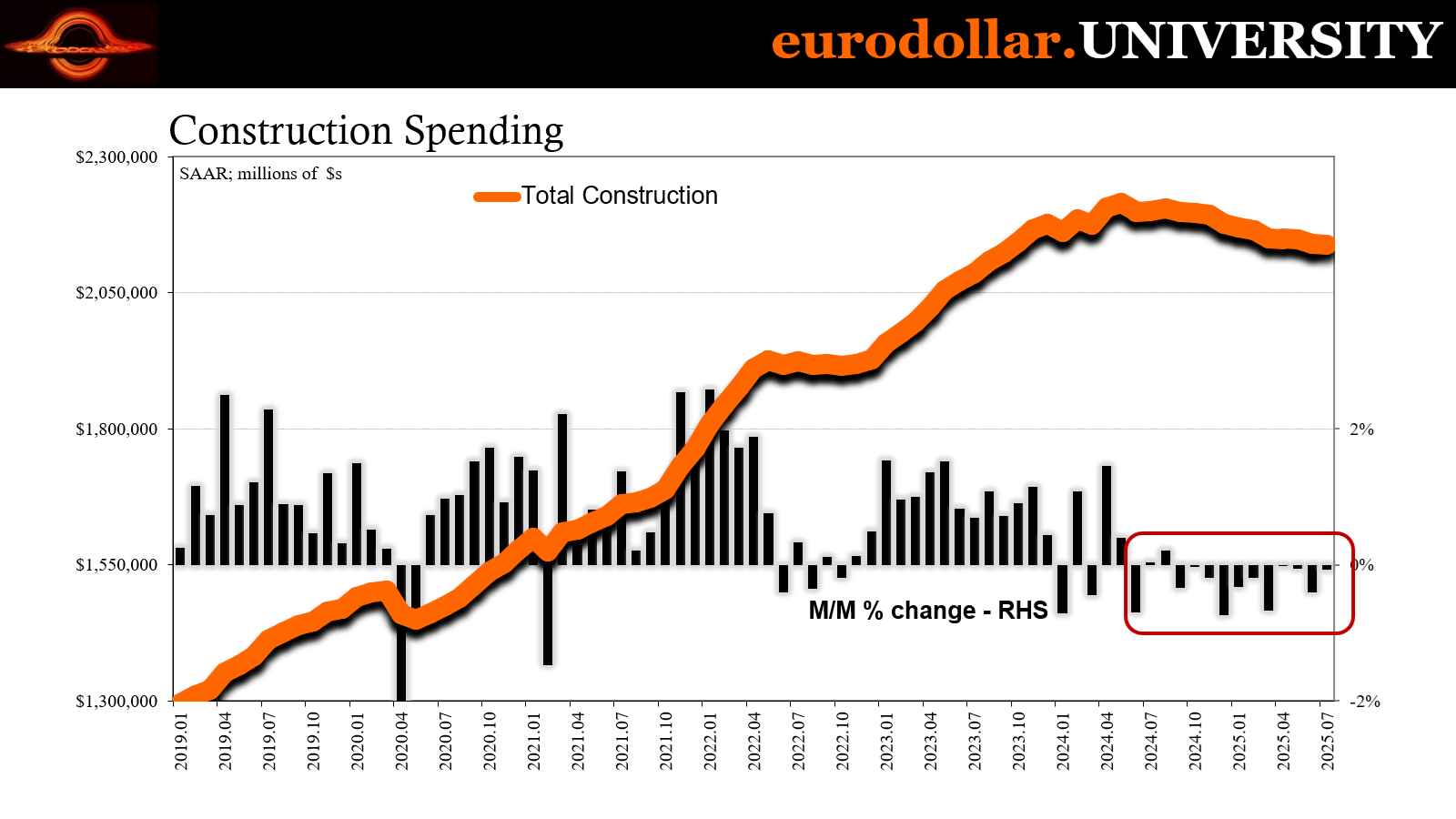

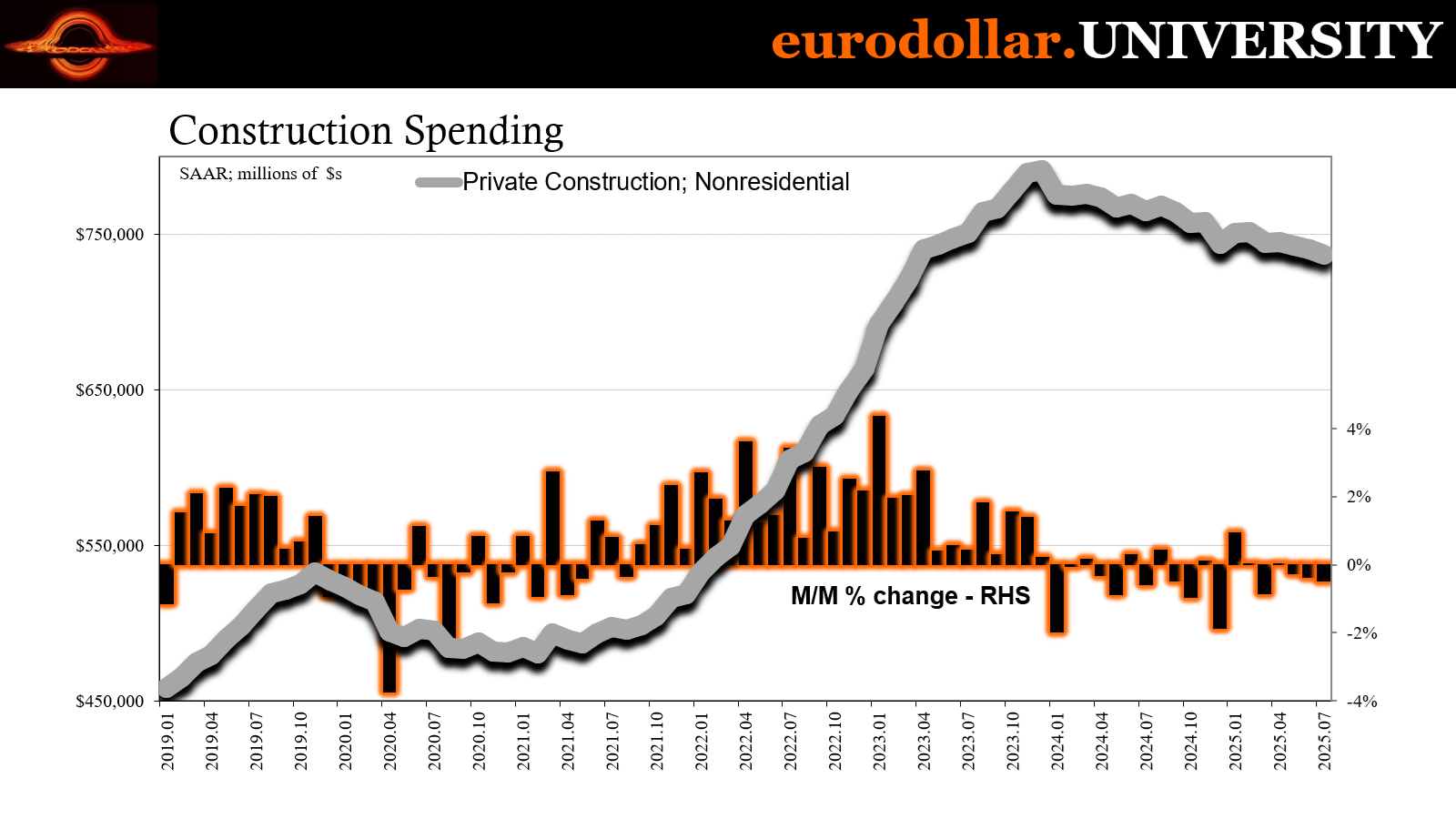

I’ve already covered construction spending and how it indirectly relates to employment; you can find that here. Census reported for July yet another decline in outlays, especially for private non-residential purposes. That’s the kind of capex retreat parallel to businesses also trimming labor utilization in one form or another, including, eventually, their number of payrolls.

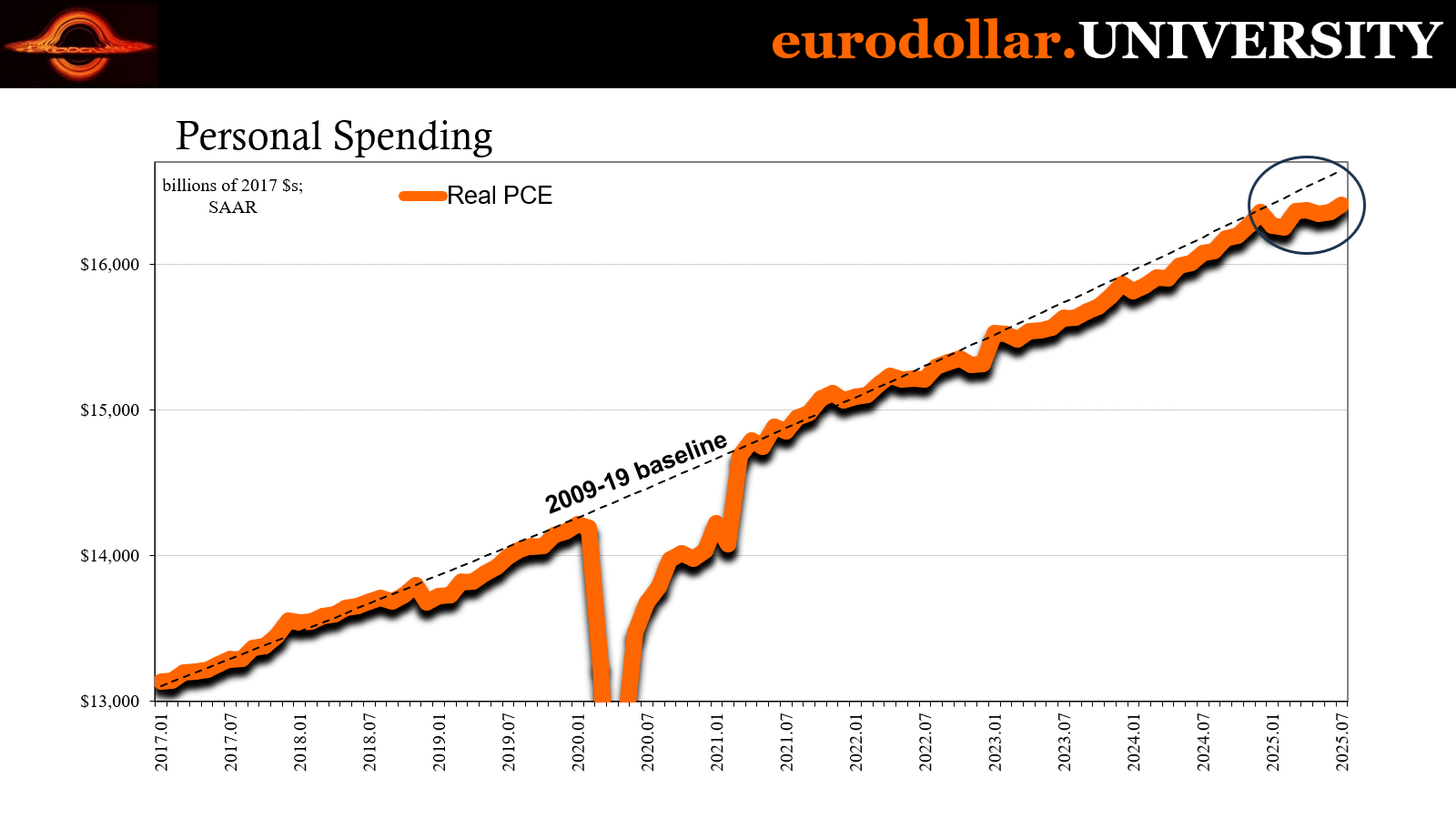

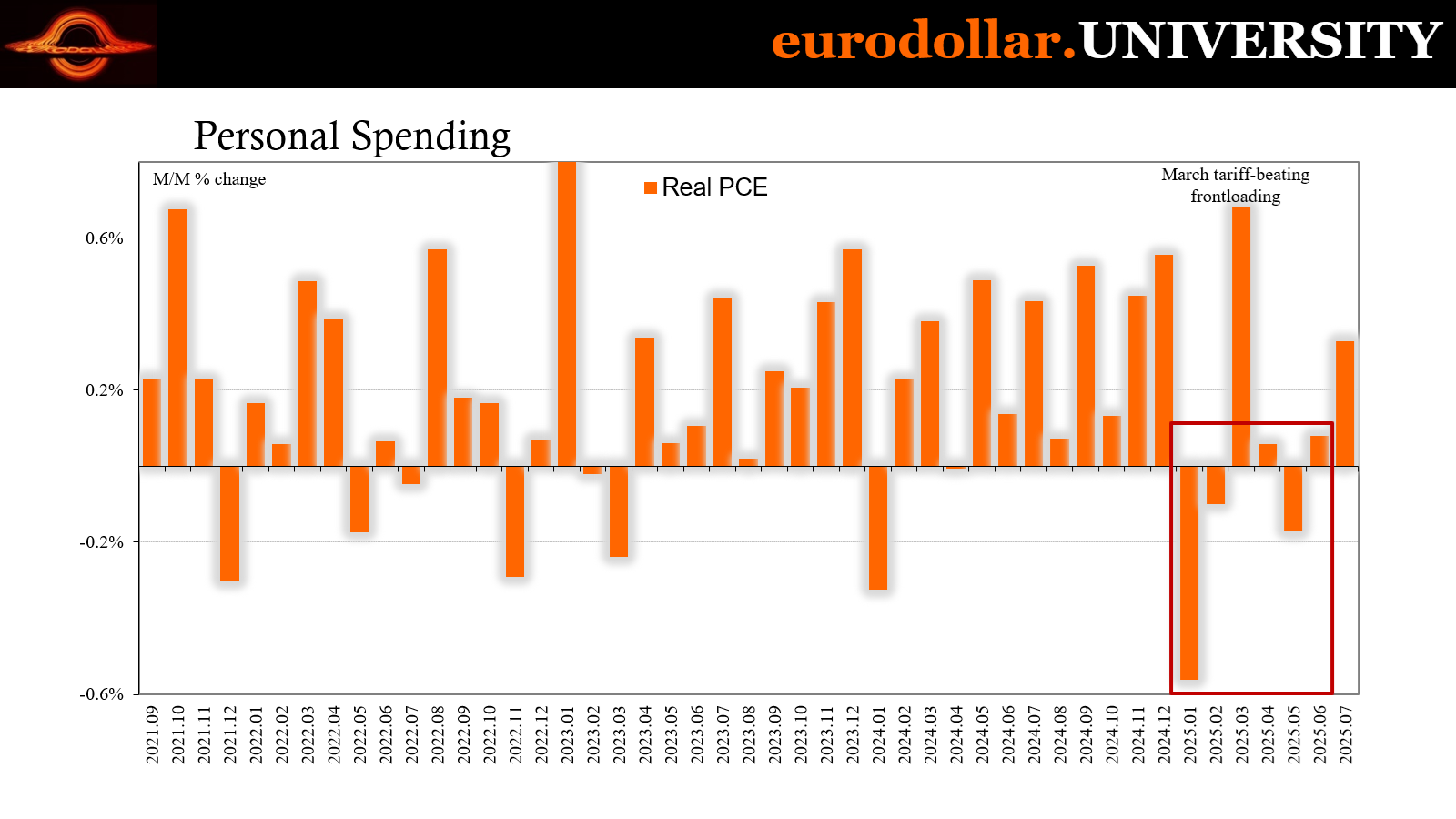

Another indirect signal of possible unemployment – which then becomes a reason for job cutting – is the consumer spending inflection. Consumer behavior has changed in 2025, showing it was never strictly or even really fears over tariffs. Spending fell off from the very start, and has yet to come back for economic reasons, as American workers sensed the reverse hitting jobs and then incomes and immediately adjusted to them.

While real Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) managed to rebound in July (the latest data released last week), that came after three prior months of a standstill (meaning contraction) and the increase in July was created mainly by more tariff distortions. Consumers ran out to buy largely autos thinking that at some point their prices just have to rise, even if there is so far no evidence that will be the case.

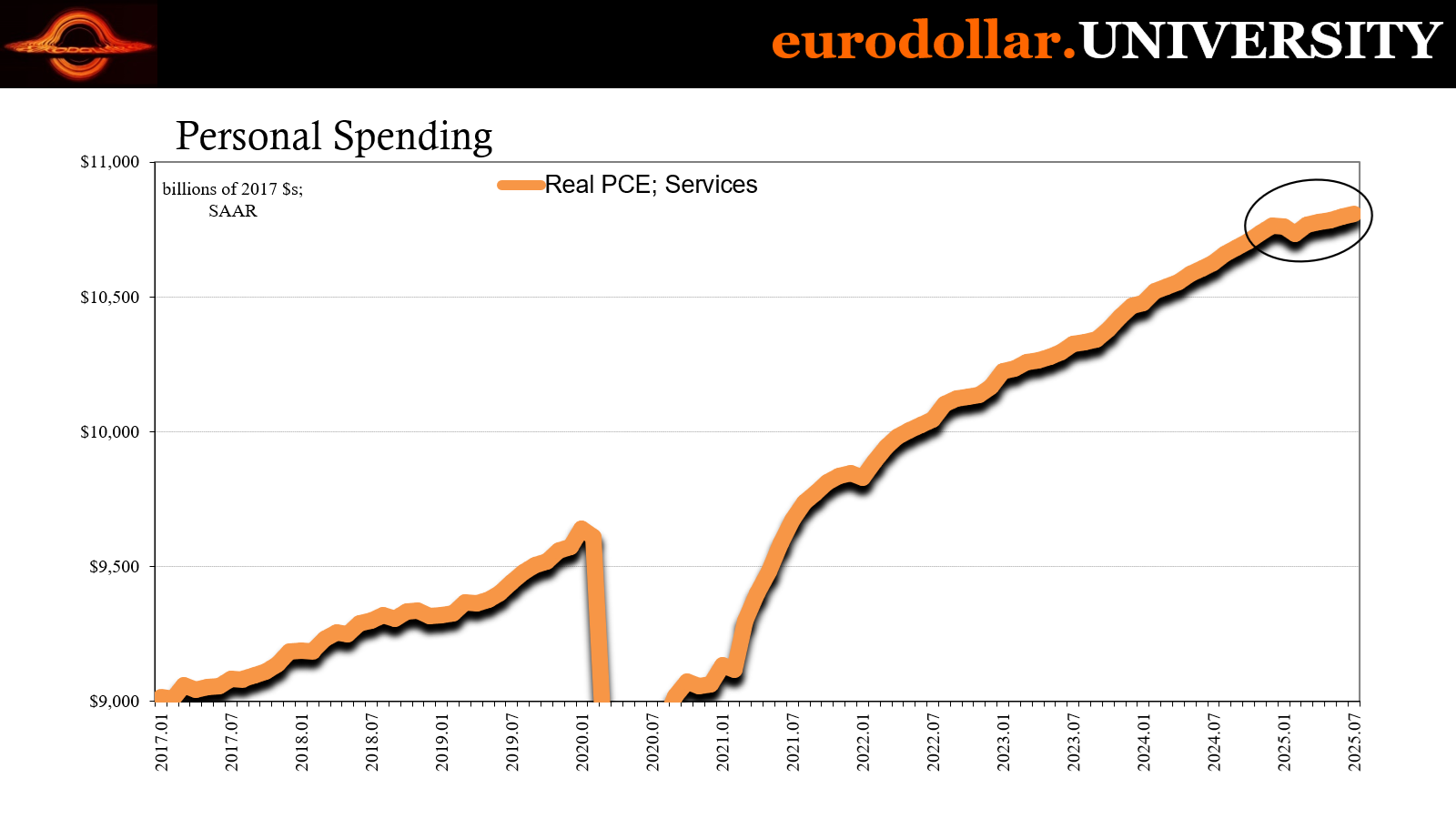

We can instead observe this baseline degradation in consumer behavior through the non-tariff distorted services sectors, the majority category for all PCE. There was no significant upturn in services outlays in July. In fact, all year, services spending has remained noticeably restrained and in contraction verifying the degree of labor difficulties as well as giving employers a reason to more fully explore flat Beveridge.

Other than fears tariffs will drive up the costs of especially big-ticket items like trucks and SUVs, consumer spending has flat-lined as employment conditions and income potential have taken a major hit, and consumers know it. The hit has gotten to be so undeniable heading toward the end of summer, even those around the FOMC are starting to see and worry about it, too.

Put that together with all these market signals and the growing pile of additional macro evidence, Beveridge himself must be frowning because he realized, as everyone should, the last place anyone wants to be is heading toward the flat piece of his curve.

All of this being highly gold-positive even if gold itself is not money nor liquid.