THE ZIRP IN SWAPS

EDU DDA Jul. 10, 2025

Summary: How negative can swap spreads go? Both the 10-year and 30-year maturities once again nearly hit a record earlier this week. Having barely moved since April, the question is, why? That contrast to stocks which have been furiously re-risking is more than enormous, there is a profound set of differences at work. Swaps aren’t just betting for a set of pessimistic scenarios, they’re also betting against interference on the forward rate curve. It all comes down to what really happened in April. I don’t mean tariffs.

How low can swap spreads go? Theoretically, there is no limit. Practically, there would have to be. Yet, over the past several years, really since the aftermath of the 2023 banking crisis, the interest rate swap market has continuously challenged these notions. Not that anyone has paid it any attention, of course.

Despite being the largest, broadest, deepest, and, in my view, most important marketplace, few “experts” seem to even know it exists let alone why. Or what it truly does. In being so central to the operation of money, commerce, and finance, prices therefore spreads coming out of there contain unbelievably useful information.

For the second time in as many weeks, the 10-year spread nearly touched a record. And when I write “record”, I don’t just mean for the SOFR variety. Employing an admittedly arbitrary adjustment factor (one that does fit beautifully in the same way Einstein’s cosmological constant once did and still does), the key 10s maturity remains in unprecedented territory where it has been the entire time since early April’s plunge, some three months afterward.

The 30-year maturity isn’t far off, having sunk recently, too. If there is a tiny difference 10s to 30s, it’s that the 30s have been in this position at least a small handful of times previously; comparisons you never want to see.

Stocks at record highs. Trade deals. June payrolls (or the conventional “wisdom” surrounding them). Even the 5-year swap is disregarding all of that noise. Following a small retracement post-April, that one is rolling over, too.

But why? How? Can they keep going lower?

The FOMC may be fixated on the next few CPIs from the United States, for interest rate swaps the story of the next stage for the world appears to have already been written and published in April. There is far more of ZIRP on this swap curve.

Remarkable given the mechanics

The first thing to realize from the swap market is where prices in it come from. Fortunately, if you are new to the DDA or haven’t visited them yet (or in some time), the basics of interest rate swaps are available at the link above labeled “conversations.” While the quartet of videos located there may not technically be conversations, they do explain in a casual, less formal way all of the basics you’ll need to fully understand these mechanics.

I highly recommend you check those out.

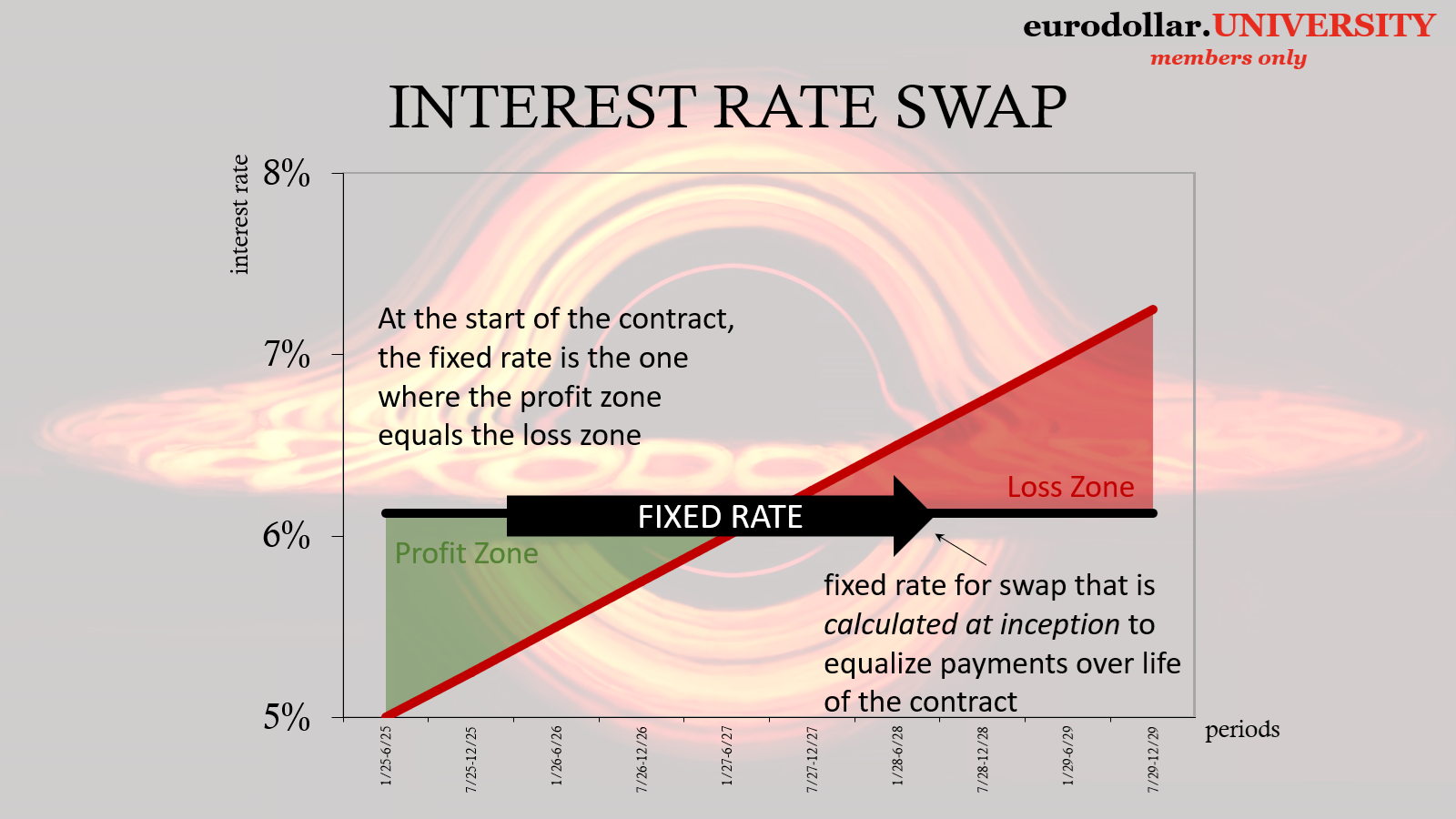

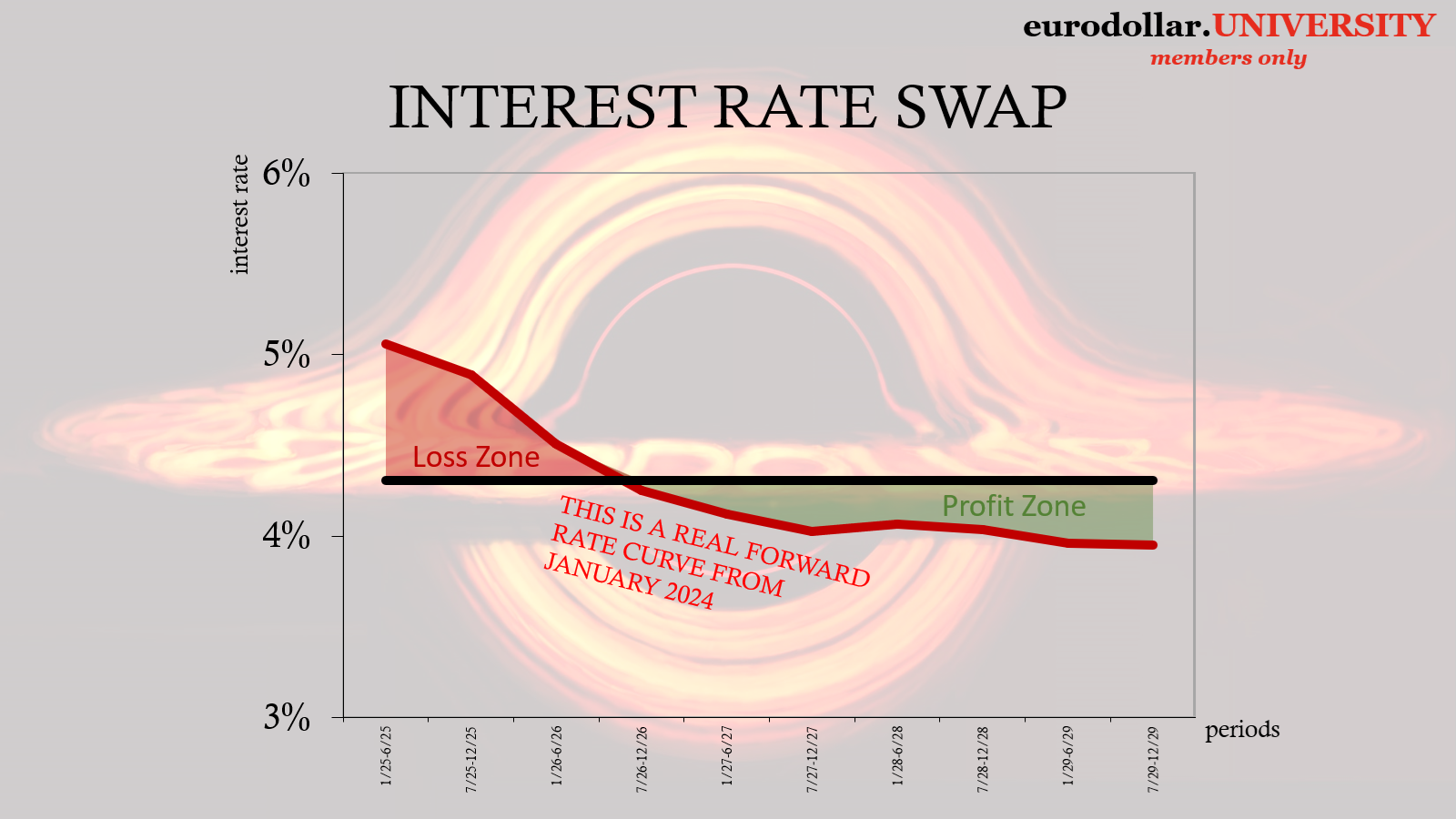

A swap rate is essentially a bet on the forward curve (SOFR). That’s how we interpret spreads; the lower they are relative to Treasuries, the more that market participants must be hedging for lower rates (on top of other monetary considerations priced into the contracts via dealers taking the other side of almost every one of them). But what if the forward rate curve is already inverted, meaning the current price of the swap already takes into account a significant downside to ST interest rates?

On the one hand, this suggests a sort of disagreement between the swap market and forward rates markets as to the extent of any forward decline. The pair often go hand in hand, yet this isn’t as surprising as it might seem. Moreover, this is highly relevant to Monday’s DDA taking on the chances the Federal Reserve really does end up reinstituting its zero-interest rate policy, or ZIRP.

According to FRBNY’s estimates on that topic, derived strictly from forward rate markets/prices/spreads, the chance of seeing zero rates remains significant (9% over the 7-year horizon, by FRBNY’s numbers) yet has come down from rather high levels back in 2022. As mentioned Monday, the New York Fed’s calculating researchers find that even too high, particularly in comparison to 2018.

Their estimates are in the same range, 2025 and 2018, yet nominal rates everywhere were far lower then compared to now. Given how the authors assume there is a relationship between the level of nominal rates and the chances of seeing zero, this is perplexing therefore chalked up to higher levels of “uncertainty” now compared to then.

That “uncertainty” is what the swap market is flashing.

A forward rate curve starts out heavily influenced by the Federal Reserve and its current stance. Eurodollar futures, for example, would almost always closely correspond to Fed policies and intentions in its closest contract “colors”, the reds and whites. Those were the first eight regular quarterly contracts, meaning closest to the present. SOFR-based contracts operate the same way.

After then, into the various other greens, blues, golds, etc., that’s where independence would show up more clearly (same as the yield curve where LT maturities act more independently than ST ones). This relationship makes sense: even if you think the Fed is wrong, it might take the Fed some time to realize it therefore it will execute its interest rate policies for some time before realizing any error. So, the reds and whites price to policy even if forward rate market participants don’t agree with why.

The exception is heavy inversion, where the market sees far greater risks in the nearer terms. However the FOMC might initially react, the reds and whites can invert, too, and have done so on several occasions like 2007 and 2018-19.

Even then, however, the amount of inversion is less than it “should” be because the ST forward rate contracts still have to price some level of interference by policymakers, even if not the fullest extent while inverted. There is always, in every case, some degree of policy obstruction in forward rates due to the unfortunate framework whereby these bureaucrats are able to manipulate ST rates for a wide range of unhelpful reasons.

Swaps don’t have that hassle, especially at longer maturities.

Going beyond forwards

If the Fed believes that rates will be higher than what the market might believe, the forward market – absent conclusive proof the Fed is wrong – will have to price some of both sides. From the perspective of other markets, like swaps, which don’t have to care about the Fed, swap rates can and do reflect this difference.

In other words, the interference from the Fed priced more into nearer-term forward rates would naturally alter the slope of the forward rate curve, even when that forward rate curve is inverted. Because swap contracts themselves are priced at inception based on that forward rate curve, the Fed-bias is embedded within that initial fixed rate price.

As more market participants in swaps agree the Fed is wrong to think rates will remain high, therefore how the “true” forward rate curve would be more steeply inverted than the actual one is, it adds yet another profitable reason to take fixed in an interest rate swap. Because of this Fed pollution, and the heavier it might be, it actually attracts more to take that position in the swap market, to take lower and lower fixed rates since the forward rate curve isn’t capturing the full set of probabilities of the future.

With more buyers and of those more willing to go lower on the fixed side, the swap spread itself goes lower, meaning more negative.

Quite simply, the more the Fed introduces unnecessary uncertainty over the future path of ST rates, the more the market disagrees with that uncertainty the more profitable it will be to take the fixed side making spreads more and more negative (and I haven’t even introduced the fact that Treasury yields, which are the measuring “yardstick” for the fixed side of spreads, are also moving lower, too!)

In very simple terms, Jay Powell’s stubbornness over “inflation” that doesn’t exist has kept the slope of the forward rate curve flatter than it otherwise would have been. This has introduced a greater incentive to take fixed in the swap market. The more that market disagrees with Powell’s inflation interference, the more negative the swap spread.

It’s not just that current rates are higher than the market thinks they should be, the market is also disagreeing on the path to correct that imbalance, too.

This, right here, is also the missing “uncertainty” from FRBNY’s ZIRP chances. The forward rate market says 9% (or that’s what FRBNY’s models derive) for zero rates in the next seven years, where these record and near-record negative swap spreads say those chances are far higher. The forward rate market is forced to downplay them because of FOMC interference, and still it works out to 9%.

Negative swap spreads to this extent are indeed a play into ZIRP potential.

One way to put it is the swap market believes – to the point it is betting massively on this – the forward rate curve needs to be much more inverted to get closer to what the swap market sees as the fundamentals, therefore a higher probability for ZIRP than FRBNY or the FOMC will be able to see or appreciate. Those fundamentals consist of macro risks and probabilities alongside those from the monetary system, or what the Fed almost always misses (especially on the monetary side, as we’ll cover below).

How low can they go?

The answer is…a lot. In this key sense, the deeply negative swap spreads are, in part, reflective of the scale of disagreement between the swap market and the FOMC’s models/stated positions as filtered through forward rate markets into the forward SOFR curve. The more Fed officials see “inflation” risks that the swap market does not, and the more downside economic and monetary risks the swap market sees Fed officials do not, the more negative the swap spread will go.

It was this, not necessarily the crash in 2008, even as that was the proximate cause, which drove longer-dated swap spreads negative in the first place. It took the Fed another almost two months to see the crisis for what it had been, finally going to zero by mid-December. Swap spreads had already plunged because, again, as inverted as the forward rate curve (eurodollar futures back then) was, swaps were saying it wasn’t nearly enough.

But with longer-dated spreads, the disagreement on the forward curve shape extended far beyond the short run.

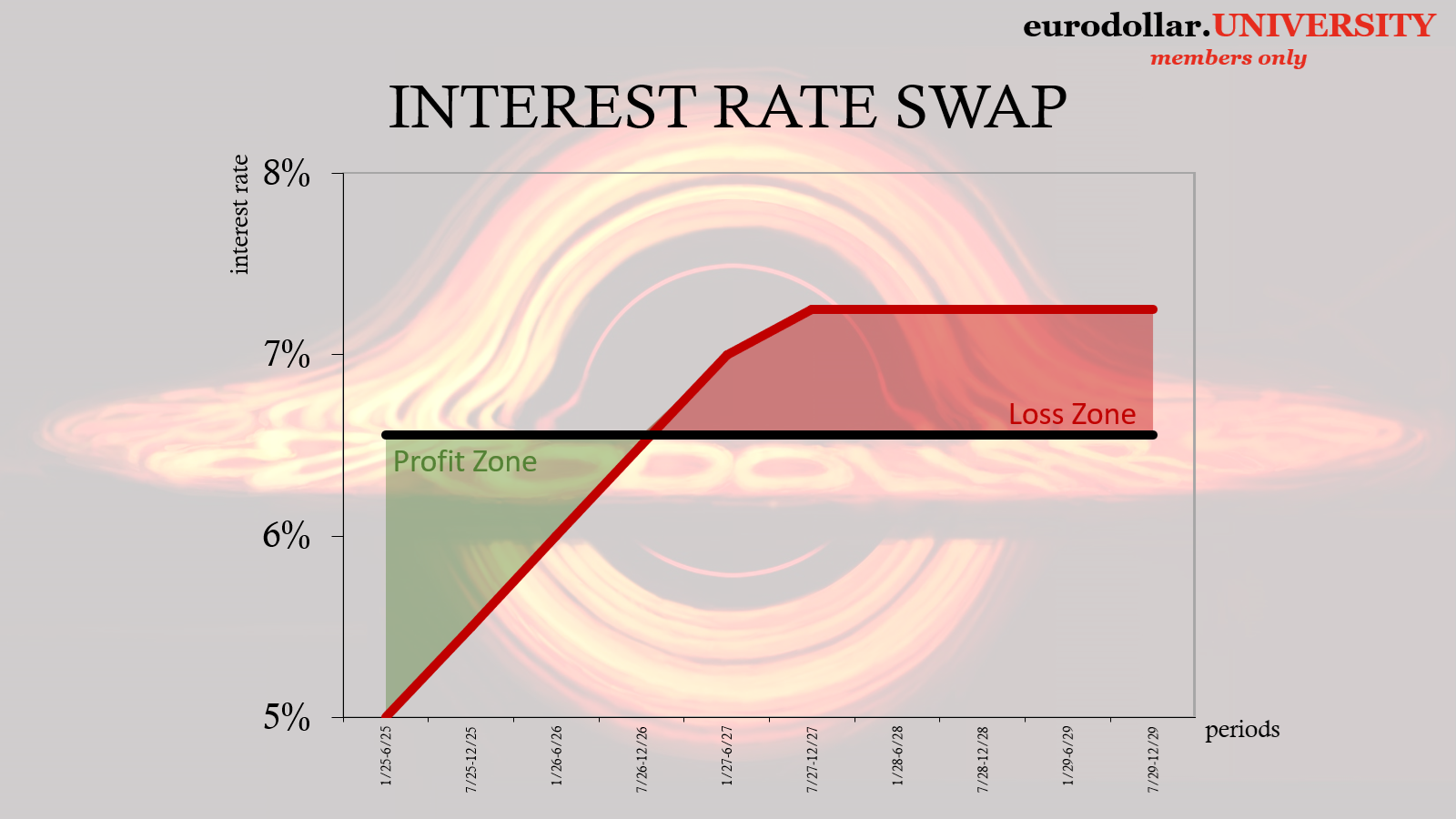

Following the event, the forward rate curve was upward sloping in part on Fed projections and confidence in the successes of its ZIRP/QE policies, therefore higher interest rates over time. The swap market didn’t see it that way, and consistently bet the eurodollar curve was too steep (upward sloping) throughout the whole of the 2010s – with the variations in spreads during the eurodollar cycles.

In other words, during reflationary periods the swap market was less aggressive in betting against the upward slope of eurodollar futures (which itself was steepening on reflationary views) therefore swap spreads decompressed somewhat. They would then return to betting against the slope of eurodollar futures (even as it flattened) on the downswings of the eurodollar cycles, such as 2012, 2015-16, and 2018-19.

In 2025, this goes beyond the swap market pricing zero inflation risk in favor of a realistic pathway way to zero. Lack of “inflation” alone won’t get the Fed to 3.5% let alone under 2%. There has to be more.

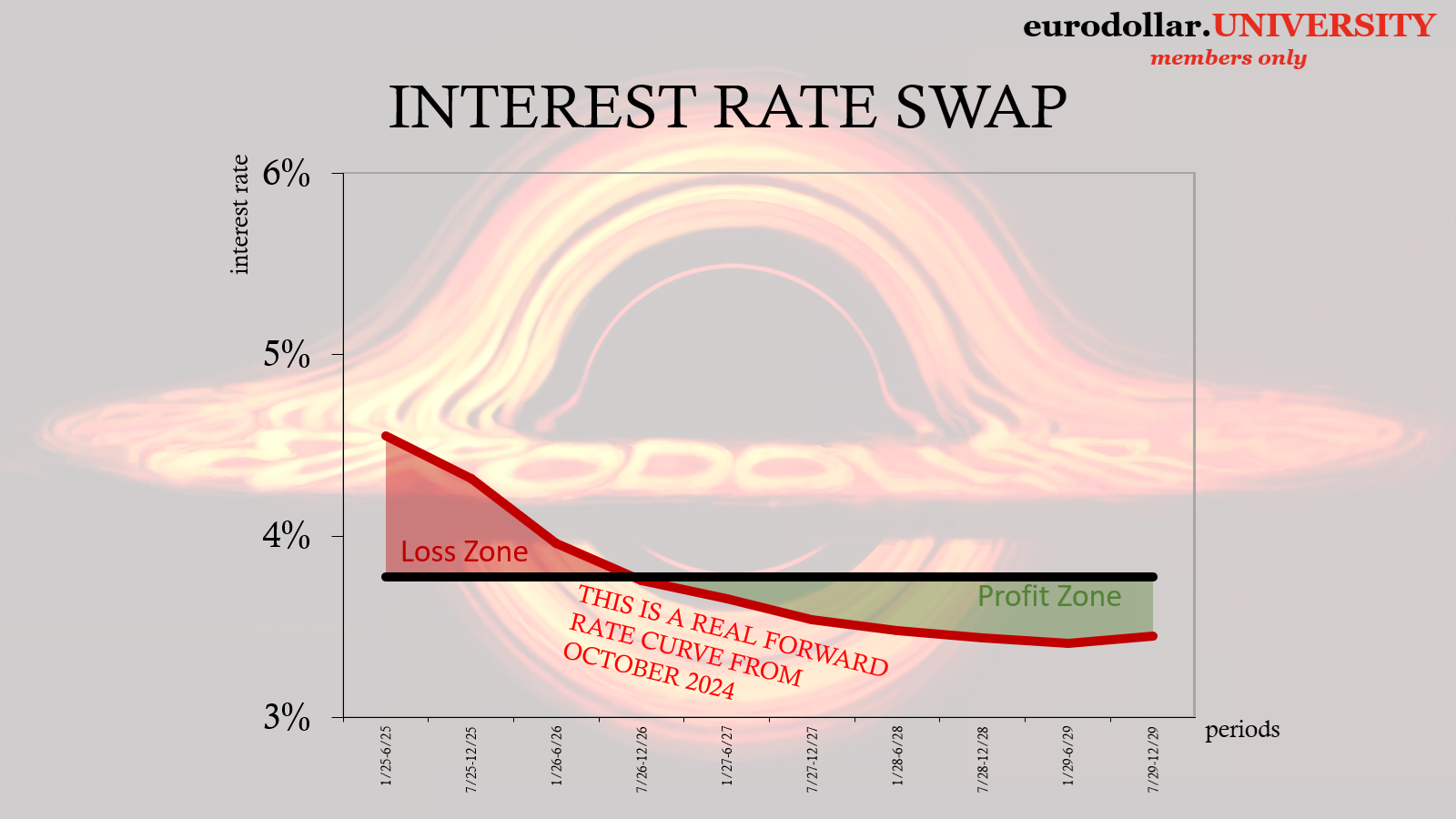

April’s plunge in spreads – seemingly to stay – does offer some critical clues. If we assume, for example, what was driving these things as low as they had been up to April were concerns over fragility in the economy as well as monetary system and financial marketplaces, then the deflationary “volatility” three months, how serious it came to be, would definitely help explain the more negative spreads thereafter.

From the swap market perspective, April confirmed fragility and downside cases - and I mean more than stocks. If you thought the world was headed in the wrong direction before then, given what happened would have only hardened opinions and solidified those market conclusions. I don’t mean tariffs, either.

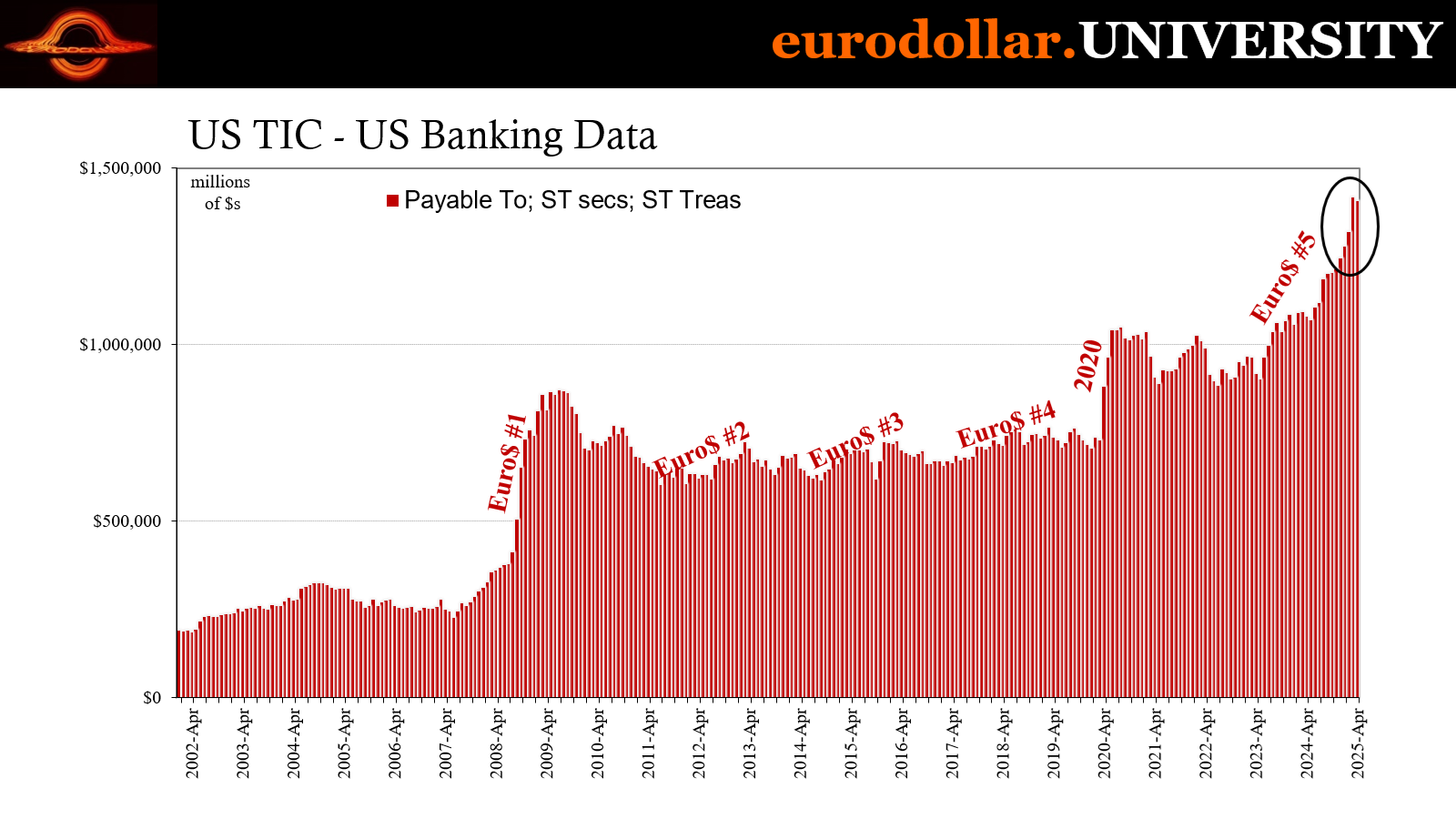

This makes particular sense from the monetary side, as potentially frightening as that might make everything. As we discussed here when reviewing the April TIC data, what it shows in significant detail is the shadow bank problem and then linking it to macroeconomic worries. Triggered by tariffs, the real issue was what happens to the funding environment for shadow banks should the economy exhibit a much clearer downturn path.

We certainly got an answer, maybe only a partial one. As noted in the prior piece, largely US-based dealer banks were lending boatloads in what could have only been emergency funding secured by what TIC showed was anything other than T-bills; most likely the same junk offshore investment funds were having trouble with elsewhere (with spreads blowing out). Even if the alternate collateral had been notes and bonds, those presented problems all their own (basis trade).

The April episode completely validated why swaps had been so negative before then, thus why they stayed that way afterward. It wasn’t a one-off, April confirmed what is a progression.

Plus, what has the Fed done since April? Inflation. Inflation. Inflation. More uncertainty, which in this case means interfering even more in the forward rate curve, flattening it out when it probably should have been steepening (more inverted) creating even more incentive to take fixed in the swap market, compressing spreads further and now keeping them there.

Making the swap to Fed divergence wider than ever.

That’s the most frustrating part. Over the past several years while Powell’s crew has waffled about on “inflation”, the swap market has easily bet more and more against the waffles, sending spreads deeper and deeper negative. While FRBNY says the forward rate market from the Fed’s position leads to a modest intermediate-term chance of a return to zero rates, if the forward rate market was closer to swaps those probabilities would properly be seen as a whole lot higher.

As to what that exactly means in macro and money remains unclear; how we get further toward ZIRP. The one easy part is “inflation”; forget about it, not happening. If consumer prices do manage to break upward over the months ahead due to tariffs, it will only be in the short run and from there add more strain to the global downside.

Assuming that was going to happen, I don’t believe it would create more negative spreads. So, in that sense, the swap market appears to be discounting that case, as well.

We do have to be mindful about some of these comparisons, the record spreads for the 10s while the 30s equal some of the worst economic cases in recent memory (2020, 2008, etc.) Equally and surpassing them post-April doesn’t necessarily mean the market is increasingly sure there will be something similar. The factors which could close this gap for ST rates, to get the Fed to finally see the world the way swaps have and do so even more post-April don’t necessarily have to be a banking crisis or locked-down crash.

But the monetary experience of April certainly doesn’t help rule it out.

Zero rates aren’t only on the table, they’re far closer to the center of it than anyone appreciates and that includes the forward rate market, if for mechanical interference. The rest of the world saw April as a one-off due to tariffs. The informed, central, imperative swap market took it as…confirmation.