VISUALIZING THE INVISIBLE AT WORK

EDU DDA May 8, 2025

Summary: Following from negative Q1 GDP and final sales (of domestic product), the BEA and BLS came together to find negative productivity, too. Though this is merely a remainder between series on output and hours, its history closely aligns with economic trends throughout. Productivity measures also aid in explaining those trends which otherwise have confounded policymakers and Economists. What these now negative numbers provide is more concrete backing for the sharply negative sentiment expressed all over, including today’s latest from the Fed itself.

A POWERFUL REMAINDER

The BLS together with the BEA delivered another sobering assessment for the economic landscape even before the labor market gets to the second quarter and its payback plus tariff shock (whatever might come from the latter). Employment was on shaky ground to begin with, more evidence which strongly indicates recession-like (forgot-how-to-grow) conditions long before 2025.

A weaker entry point coming into 2025 does matter.

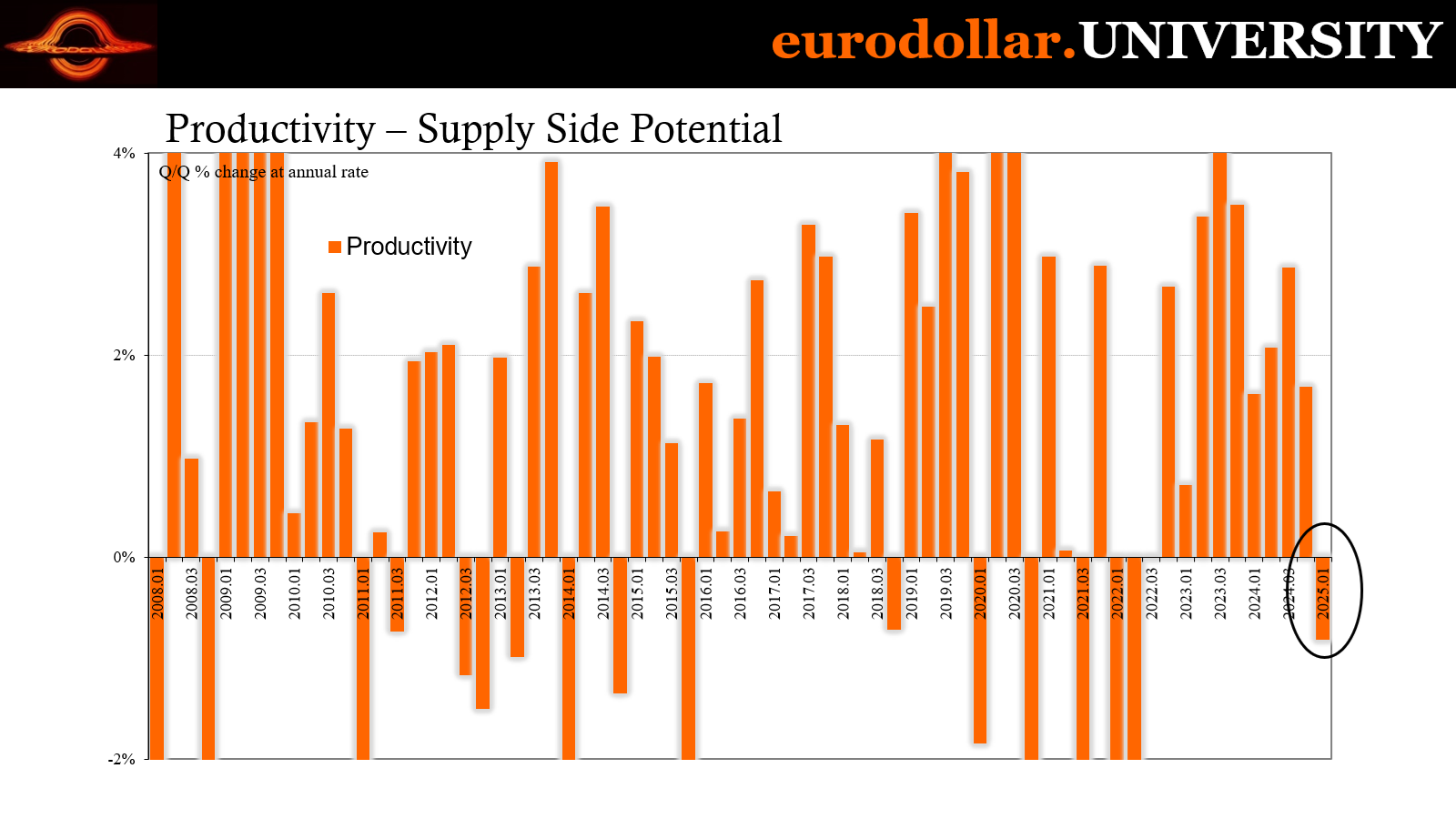

The setback in output in Q1 (BEA) combined with a slowing if steady jobs situation (BLS CES) sent productivity negative for the first time since 2022. Productivity, as it is measured, may be little more than the remainder between estimates of private output and those detailing the numbers of hours worked, yet there are legit and intuitive reasons why the series fit together this way, making productivity estimates as a rough yet validated approximation for that complex relationship between employer and employee.

Negative productivity is just what it appears to be, a warning that employers are now far more likely to take even more action to address growing shortfalls.

The potential for just that has sent consumer fears over jobs and incomes into the stratosphere. The latest data displaying as much comes from the Federal Reserve itself. While Chair Powell yesterday sounded somewhat more confident (as discussed), his actual message was more nuanced. In short, if he came off sounding assured on the economy and jobs that was merely a bonus to the Fed’s dilemma.

The truth is neither he nor the Fed’s data indicate anything like solid optimism. And put together with the BEA/BLS figures, there is every reason to be anything else. Plus, as also pointed out yesterday, the negatives aren’t limited to purely sentiment; spending and credit have flashed warning signs, too. Combined with productivity, while maybe not quite the final confirmation everyone is seeking, they are a powerful warning how all the necessary factors are at least aligning.

Expectations and distortions

To further clarify the FOMC’s position, one factor keeping the committee from acting in the face of all these suggestions of full-recession developments is expectations. What Mr. Powell said at his press conference was that policymakers (thereby their econometric models) are anticipating tariffs to produce only one-time price changes, a price shock.

Obviously, neither the Fed Chair nor any official text will ever again use the term “transitory” again, yet that is their (and ours) base case regardless of how anyone will characterize it. Instead, official “inflation” fears rest solely on expectations; or, more precisely, the theorized possibility the one-time (or short run) price shock will transmute somehow into broader expectations that consumers and businesses then act out.

Expectations become “unanchored”, to use their terminology. As Powell put it:

Our obligation is to keep longer-term inflation expectations well anchored and to prevent a one-time increase in the price level from becoming an ongoing inflation problem. As we act to meet that obligation, we will balance our maximum employment and price-stability mandates, keeping in mind that, without price stability, we cannot achieve the long periods of strong labor market conditions that benefit all Americans,

Because Economists are left with voodoo where it comes to consumer prices, and the Fed is the biggest practitioner among its peers, any price spike must be considered “inflationary” no matter how many times the prior ones aren’t. Worse, policymakers believe – or want the public to – the only reason the supply shock didn’t alter expectations and become the 1970s were their 5% ST rates, even if the idea is patently ridiculous.

Starting with the fact prices began to calm down with the economy in 2022 (more on why below) just as central bank policies were getting going, long before the long and variable lags purported to rate hikes.

More to the point, there is no connection between expectations and inflation. This entire theory owes to Robert Lucas needing some way to eliminate infinities in his overly complex economic models; expectations is there because the math needs it to be not because there is any real reason for the variable.

Believing high rates held down prices plus expectations possibilities for prices, the Fed is stuck by its own ideas.

The other factor leaving the Fed to waffle is this view sentiment is the only current evidence for the downside. According to the official view, the data so far doesn’t go nearly far enough to confirm increasingly terrible sentiment metrics. Unless and until “hard data” shift more toward the bad end of the spectrum, the expectations theory on one-time price hikes will keep the wafflers waffling.

Powell brought up GDP as an example of data that wasn’t “bad enough” in exactly the way I’ve been saying. While Q1 output was indeed negative, it was also skewed by imports. Looking through those distortions, Powell cited final sales (to domestic purchasers) as being “solid.”

Productivity, however, begins with the other final sales, the one which didn’t look good by any means, the final sales series which fell by the most since 2020. Since productivity even as a mathematical remainder does correspond with both output and labor conditions, there is far more of an empirical basis for this and therefore sentiment than what the Fed is using to prop up its institutional expectations bias.

Productive productivity

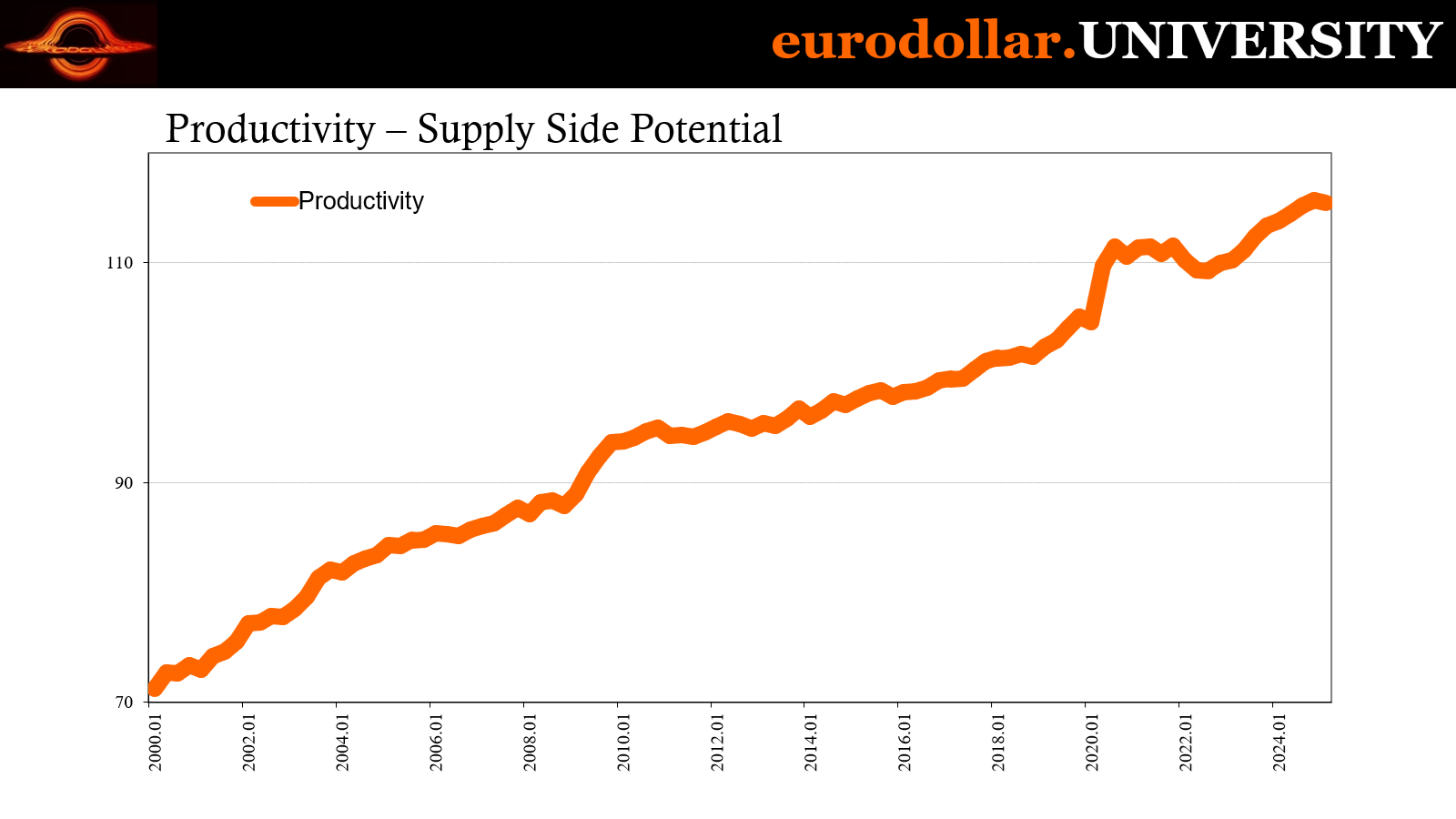

As a concept, the idea is simple enough. Businesses combine capital with labor and get more out of both. Coming from innovation and greased by monetary finance, it’s the invisible secret Adam Smith implanted in modern consciousness. More productivity means rising living standards, more sustained and profitable business that gets shared and recycled back to labor in more jobs and higher pay. Not by instigated distortion, rather organic combinations that can’t be replicated by centralized approaches no matter how much econometrics models potential successes.

Measuring productivity is trickier given its more esoteric components. Therefore, as a practical solution the BLS and BEA got together and presumed the remainder left over after comparing the one’s output with the other’s labor yielded something close to the concept.

For Q4, the BLS believes total private hours were slim yet grew by +0.84% (q/q annual rate). Since the BEA pegged private output at an annual rate of +2.53%, statistical productivity is simply the difference, +1.69%. That’s not great yet hardly awful, already consistent with the general tone of the economic environment of the time.

The economy wasn’t falling apart, though it wasn’t thriving, either, therefore the ongoing serious questions about labor and employment.

Q1, by contrast, whereas Powell and the Fed dismiss the negative, the BEA’s figure on private output did contract, -0.26%. And since the BEA says hours slowed only somewhat from Q4, +0.55%, then productivity must also have contracted by the distance between then two, -0.82%. The only way by which business could have kept productivity positive would have been to outright reduce hours (and likely the number of employees, too).

For a single weak quarter, that might be an overreaction. Since this isn’t merely one quarter but a string already lasting several years, that’s the danger.

Productivity is therefore something of a profitability measure where it comes to use of work and workers. If it is negative, that means – in cyclical rather structural terms - there isn’t enough business coming in the door to effectively utilize all employees to their maximum efficiency. Negative productivity is a sign that businesses may have to reduce their work component to get back to profitability, generally speaking to be better align costs with revenues.

This explains what to most Economists remains a mystery to this day. Productivity during the 2010s Silent Depression was continuously low, defying the QE/recovery story. Worse, this was strong evidence the labor market never did fully (or all that much) recover because it also provides the reason why.

From a structural standpoint (the “supply side” meaning economic potential), sustained low productivity is supposed to be a lack of innovation and investment; firms not putting enough into their own capacities to execute Smith’s invisible hand to a sufficient extent. Thus, Economists and central bankers (same things) took low productivity in the 2010s as something else structurally (starting with demographics) holding back business investment therefore letting QE off the hook for its cyclical shortfalls.

While there is some truth to it – business didn’t invest largely due to the monetary breakdown – there is another major component to low productivity. From the cyclical perspective, immediately after the 2008 contraction cautious firms carefully began to add onto their payrolls anticipating (if somewhat skeptical) a plausible (sounding) recovery.

But then the economy didn’t get going, the Great not-recession. Productivity suffers because there is no recovery, not a real one, and therefore no matter how many times each successive Fed Chair talks about a tight labor market, what use do employers have for even more employees?

Low productivity in this context simply confirms too many workers for not enough work. Why hire anyone else? And if firms don’t hire, the economy is, at best, stuck. Pure depression economics that no Fed official can ever admit to the public.

And this fits with a range of other data, including JOLTS hiring, not to mention everything on the participation problem. Productivity showed that there was never a reason to fully rehire all those workers laid off in 2008-10.

For our more immediate purposes, that means two things: the BEA/BLS measure of the concept may be a mathematical remainder yet it fits with real world circumstances, economic history, and is able to help explain both in a consistent manner that covers all the facts; second, this means negative productivity also holds very real potential implications for the labor market in 2025 for all the reasons stated above.

Cyclical productivity

If low or even negative productivity suggests, in cyclical terms, not enough business for the workers at hand, then flagging productivity over the past several years now becoming negative in Q1 2025 gives the labor market a major problem – one that consumers are talking excessively about to consumer confidence surveyors.

This isn’t a tariff thing, either, rather a forgot-how-to-grow thing. Start with the relationship between productivity and hours worked. As you might expect, there is an inverse one and it is fairly strong. Not only that, this correlation goes back decades.

From here on, I’ll plot the hours index on an inverted scale so you can clearly see how strong this relationship has been. This isn’t random mathematical coincidence.

First off, the 2010s. Because productivity never really got going, hiring wouldn’t. There wasn’t enough work for the too-few workers business did add. There were, however, pockets of reflation, such as 2014 (what was known at the time as “the best jobs market in decades” in order to sell the public on QE finally achieving success).

What you see (denoted by the green double arrow) in 2014 was an uptick in hours worked without any downtick in productivity. That meant more workers and work was being led by an acceleration – a very modest one – in business and economy. Sadly, it was spoiled by the globally synchronized downturn which followed in 2015 (Euro$3).

The middle 2000s is another example. Coming after the “jobless recovery” of 2002 and 2003 (the “giant sucking sound”), hours finally picked up in 2004 along with job growth (the number of workers rising along with the number of hours). Productivity didn’t decline offset hours because the real economy was driving the recovery in labor.

Downturns and the depression economics, on the other hand, those are when business slows down too much leaving employers with too many employees. The most obvious instances are the outright recessions, shown on the historical chart here going back to the 1960s (the figures themselves date to the 1947 and are consistent all throughout).

There are two non-recession examples more recently, beginning with 2019. Productivity began to slow (red double arrow) while hours were growing. That was Euro$4 impacting the American economy and labor market, not just those overseas, all throughout 2018 setting everything up for the slowdown and maybe recession in 2019.

This was the entire reason why the Fed was cutting rates that year rather than raising them as expected driven by inflationary full employment – productivity was confirmation of weakening underlying fundamentals contrary to the official view. Sure enough, hours began to slow in 2019 which then allowed productivity to rebound.

In other words, the rebound in productivity was the signal businesses were making the “correct” choice to better align (less work) their labor costs/utilization with the actual economic environment, rather than the perpetually optimistic version proffered by the mainstream. There is every reason to believe had COVID not come along the Euro$4 downturn would’ve become self-reinforcing; markets certainly believed there was a good chance (inversions) and so did the FOMC (rate cuts).

Twenty twenties

The government’s productivity numbers even help explain – and validate – the forgot-how-to-grow recession and its hold on the labor market. Those initial rose sharply during the 2020 contraction because, like any cycle trough, companies shed more workers than they otherwise might need to (productivity also works in the other direction). Economics (small “e”) is imprecise, filled with errors and judgments.

But as business began to recover, firms quickly found there wasn’t enough actual work to justify recovering all the jobs lost (including jobs that would’ve been created yet never had the chance to be). Productivity began to reverse in the first half of 2022 (before rate hikes during the “technical recession” that is no more if only because of revisions). That was the signal companies were bringing back more labor than they actually needed, even if it was covered up by the price illusion and that nonsense about the “labor shortage.”

In other words, employers responded to this cyclical drop in productivity exactly the way they always had: hours flatlined thereafter, a legit contraction in labor usage even if layoffs remained absent. The hours index has been basically sideways since – the hiring freeze – while productivity had turned higher signaling that companies were correct to have realigned workers (again, recession).

The chart shows how this shift from 2022 into forgot-how-to-grow appears for both productivity and hours exactly like all other prior recessions, if not to the same degree only because of the absence of job cuts. And that lack of layoffs is itself explained, in part, by productivity, showing how there was no excess of workers brought on to be laid off; companies had stopped hiring well short of there.

Just like the 2010s.

But with that rising productivity combined with last year’s artificial factors, hours began to tick up again in 2024 however modestly. As a result, productivity growth slowed because there wasn’t enough actual output to support the hours. One way to interpret this is that employers began to bring some workers back anticipating better output either later in 2024 or by 2025.

Q1’s stumble in output and therefore productivity is therefore a critical development and warning. The economic climate doesn’t actually merit the hiring and work. Realizing this, and with hours out of alignment again, the solution would be to realign work and output in the same way as before, if not more drastically via cutting employees, too, in order to reduce the growth in hours (if not hours in absolute terms).

Powell is wrong to downplay the negatives in the economy as well as claim there is no confirmation to them beyond sentimental surveys.

In fact, it’s more likely that these estimates are picking up on real processes which is then driving negative sentiment. Consumer sentiment, in particular, is really workers’ perceptions of jobs and income potential. If they are increasingly pessimistic about them, they’ll say so.

Workers hear things and talk to other workers. They know when it isn’t going well at the job, when management is making noises, and when those noises might become more serious.

The productivity data describes a climate that is increasingly becoming something like that. After all, it did the same thing three years ago which then became the forgot-how-to-hire recession. Back then, consumer sentiment also plummeted with some part in that plunge played by the sudden shock of what was supposed to be a red-hot labor market going ice-cold with hiring and hours (the other part the lost purchasing power combined with flagging job prospects).

FRBNY’s Survey of Consumer Expectations for April, released earlier today, was riddled with job and income fears. Job finding expectations (lack of hiring) dropped to their lowest since the lockdowns – a level that is equal to those as well as the early 2010s as described above. Job losing expectations, or unemployment expectations, remained unusually elevated for the second straight month.

Income expectations (median) slid to the lowest of the cycle so far, too. And they did so primarily as those at the lower end of the statistic range were increasingly worried they’ll see zero income growth over the year ahead; i.e., layoffs.

While it should be noted April data on expectations are going to be skewed by the dramatic upset in markets, we should also keep in mind how the same upset last August wasn’t treated in nearly the same way. This is far more serious.

And it isn’t purely overly-emotional consumers shouting about their 401k’s. Sentiment is tied to jobs, and productivity provides more solid evidence for the fundamentals of the labor market expressed in these widespread sentiments.

This may not be the overwhelming proof Jay Powell (or the NYSE) thinks he needs to shift him off the expectations fence, however it does align with so much more that says the probabilities that evidence does materialize is getting to be as high as sentiment is low.