CENTRAL BANK WEEK, PART 2

EDU DDA Jun. 18, 2025

Summary: Sweden cut. Bills are feeling the debt ceiling. Again. But the Fed didn’t just sit there doing nothing, it actually offered nothing. Its entire purpose is at least to pretend to be accomplished, to be in a position to offer guidance and clarity no matter how inane and off. This year’s FOMC can’t even manage to do that - and they just told the world.

I GOT NOTHING, SAID POWELL.

The data shows more certainty, not less. Fed Chair Powell, however, says his visibility is increasingly less certain, not more. He and his fellow policymakers aren’t without their reasons, as we’ve been discussing. The issue is really whether those are in any way credible, if they’re even based on evidence rather than raw guesswork.

We both know the answer to that.

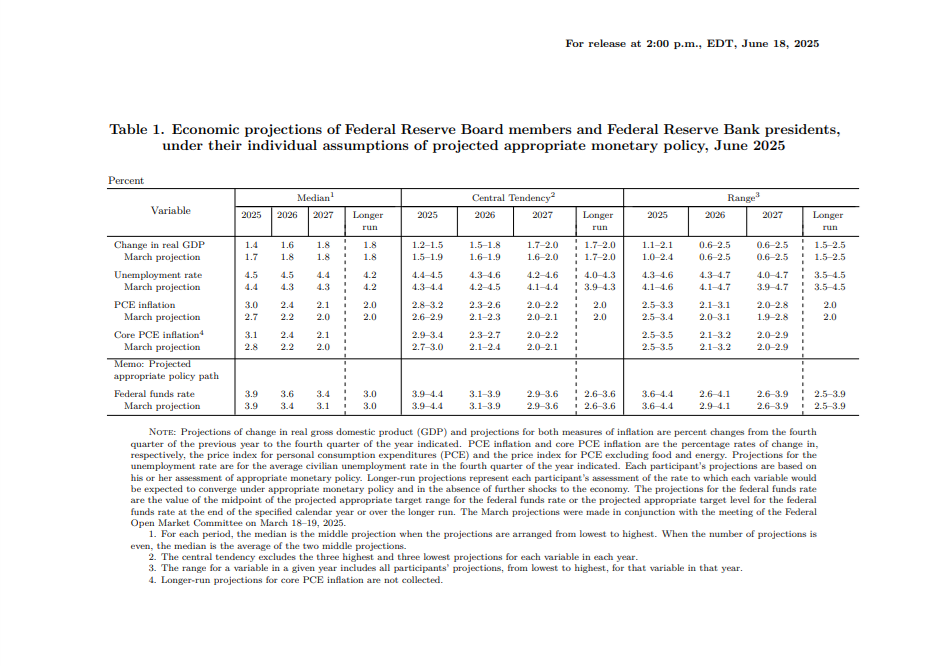

While some dots shifted according to today’s update from the FOMC, if there is anything worth taking away from the quarterly projections (updated from March) it’s that the models are getting weakness on the economy side even if blaming tariffs for it. No matter, GDP projections are now down firmly in the danger zone Powell says he doesn’t see.

Also, the debt ceiling is finally impacting bills. Some housekeeping is in order in that critical part of the monetary system, what to be aware of at a relatively early yet crucial juncture for maintaining collateral and money flow with market risks of renewed aversion flare-up increasingly likely (sorry, Jay).

Finally, Sweden’s Riksbank did as expected, lowering its benchmark rate by a quarter, now down to exactly 2%. That one was an easy one given the deterioration in the Swedish labor market owing to too long stuck with forgot how to grow.

Tomorrow, Switzerland and England.

Briefly Swede

There weren’t any surprises out of Stockholm. Defying its early confidence (where was that uncertainty?), Riksbank policymakers voted to lower the benchmark rate fully down to “historically low” 2%. As detailed yesterday, the reasons for going back on the prior official forecast are easily explained in a single chart.

Our few additional charts help complete the picture, explicitly illustrating why the labor market keeps falling apart (a clear example of forgot-how-to-grow). When the unemployment rate which wasn’t supposed to be rising much has maintained its trend to the point that it is now nearly the same as both 2020 and 2009, no central bank is going to sit there and do nothing.

Rate cuts don’t and won’t help; Sweden in 2024 and 2025 being an obvious example. Trade and tariff “uncertainty” are being given the blame, yet like Canada’s claim to a soft landing the Swedish data doesn’t fit that narrative. This thing didn’t start in March or last November.

In addition to lowering rates today, Sweden’s central bankers also confirmed they fully expect more policy action coming:

The forecast for the policy rate entails some probability of another cut this year. The lower interest rate will stabilise inflation at the target and contribute to strengthening economic activity.

Re: the second sentence. The Swiss said the same thing about their rate cuts and are instead going to be at zero (maybe negative) tomorrow morning because rate cuts don’t contribute to strengthening anything, let alone stabilizing “inflation” which keeps coming up missing in all these places. I’ll keep pointing out – and these central banks will keep proving – rates cuts are only ever a reaction to weakness.

Instead, the most relevant aspect to the Fed’s plight is that in spite of sharing common theological assumptions these other central bankers unlike those at the FOMC seem to be very confident on both inflation and economic weakness; none of the one and way too much of the other.

LOOK AT WHAT TARIFFS HAVE DONE!!!

TODAY’S FOMC WASN’T THE WIZARD OF OZ; IT WAS OFFICE SPACE

FOMC show

To begin with, understand the true purpose of this whole thing. It is a spectacle, closer to a religious ritual whose purpose is to legitimize the incompetence and powerlessness of policymakers. The press conference, more than anything, has morphed into the movie; it is really easy to picture Powell standing there answering questions using the thundering voice, in front of the frightening pyrotechnics, being the menacingly hovering green head of Oz’s wizard.

In order for it to have any prayer, though, the floating Powell avatar has to - at minimum - come across as credible. That means the Fed Chair has to provide some confident explanation for whatever state of the world to display some of the presumed expertise and genius, if not take it further to then, hopefully, describe a plan on what to do about it.

Ben Bernanke was an expert in playing Oz. No matter how bad it would get – and it got historically bad – nothing would rattle the guy. He came across as on top of the situation though the Fed was far from there, continuously talking up the next big idea while effectively skating by the inconvenient fact the last one failed. Bernanke played the role expertly.

Powell, not so much. Today was a perfect example. Wishy washy, anyone watching his performance left with the burning question the Bobs once asked Peter (Office Space reference): what would you say you do here?

He’s supposed to know what’s going on with the economy. That’s the entire purpose of the modern post-money Fed! The guy didn’t just refuse to offer answers, those he did provide were perception and speculation rather than some with tangible backing.

FOMC models modeled-down GDP growth for 2025 to a range of 1.2% to 1.5%. It had already been whittled lower to 1.5% to 1.9% back in March from 1.8% to 2.2% from the December projection. For unemployment, then, the forecast rate was pushed up to 4.4% to 4.5% for this year. If you remember, last year the FOMC had predicted unemployment would top out at 4.1%, thereabouts.

None of this is like Sweden, as Mr. Powell did repeatedly point out (of course without referencing anything close to Scandinavia; from Economists perspective, little to nothing exists outside the domain they’re operating in anyway). It was only recency bias:

The U.S. economy has defied all kinds of forecasts for it to weaken, really over the last three years, and it’s been remarkable to see…again and again when people think it’s going to weaken out. Eventually it will, but we don’t see signs of that now.

“I haven’t failed completely yet” is far from the clincher Chair Powell may have hoped.

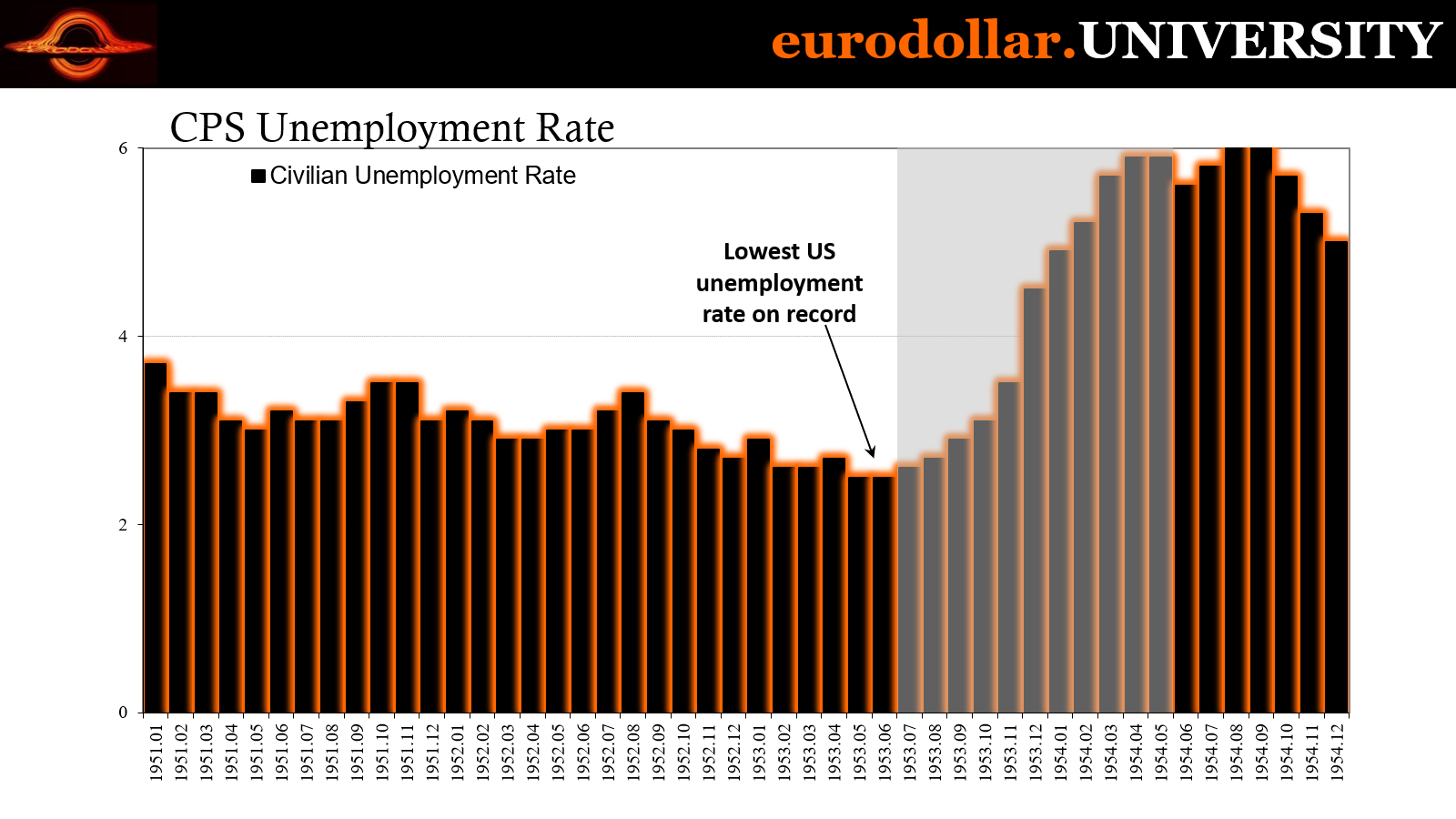

This also rests on the binary of orthodox practice: either the economy is in recession – as defined by orthodoxy – or it must be fine. The entire point behind forgot how to grow is to demonstrate with actual (and broadly found) evidence that’s not close to true. Regardless, even assuming the US was legitimately booming since 2021, that still doesn’t mean the economy couldn’t abruptly weaken in 2025 for a variety of reasons; almost every postwar recession the NBER declared began a month or two following the prior cycle’s lowest point for the unemployment rate.

America’s record low unemployment rate was set the very month prior to the start of an officially-declared recession. Powell was left scrambling, employing weak recency bias rather than proactively settling the queries employing solid analysis. This was the schoolyard equivalent of the I-know-you-are-but-what-am-I routine.

W. M. MARTIN, JULY 1956: The U.S. economy has defied all kinds of forecasts for it to weaken, really over the last three years, and it’s been remarkable to see…

Weakness, is it enough?

Looking ahead, the labor market and consumer economy recently do seem to be forgetting even more about growth than both had previously. Part of that weakening forms the basis for these GDP downgrades. What separates the FOMC here from Riksbank is simply the Fed believes it isn’t enough deterioration and that, unlike Sweden, it will remain manageable throughout.

On what basis do the models rest these claims? Random guesswork.

Even Powell was at a loss to really back up this claim (thus, his unserious retort). They believe the economy will be relatively fine because they believe the economy will be relatively fine. The scarecrow has company…

Over on the “other” side, where it comes to “inflation”, officials only hope prices will remain relatively anchored but have little or no confidence they will be. It starts with what I wrote about Monday, the whole strategy shift clearly being practiced already though the review hasn’t come close to being finished (as noted, the review itself is merely more cover for what the FOMC has already done).

No price changes have thus far materialized from tariffs, yet policymakers believe that will change because “everyone” says so. Data dependent? Powell said:

Everyone that I know is forecasting a meaningful increase in inflation in coming months from tariffs because someone has to pay for the tariffs. It will be someone in that chain that I mentioned, between the manufacturer, the exporter, the importer, the retailer, ultimately somebody putting it into a good of some kind or just the consumer buying it. All through that chain, people will be trying not to be the ones who can take up the cost but ultimately, the cost of the tariff has to be paid. And some of it will fall on the end consumer.

Had the Fed a reasonable and useful working knowledge of inflation, it would immediately see the above prospect as a one-sided negative for the economy, not the inflationary side. Instead, Powell again failed to put forward any solid interpretation whatsoever.

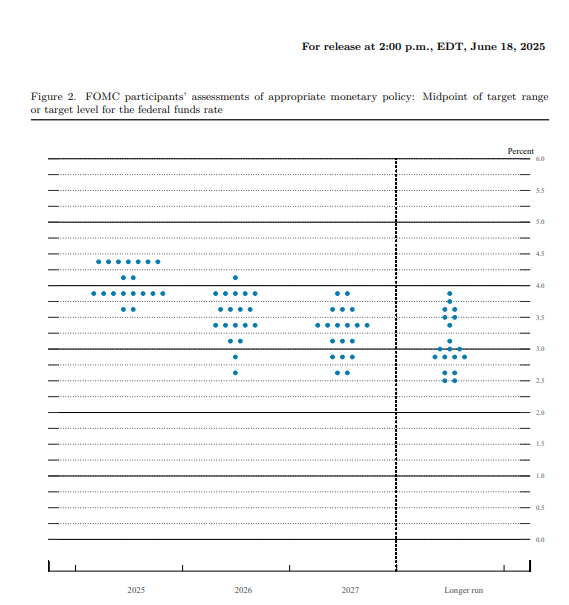

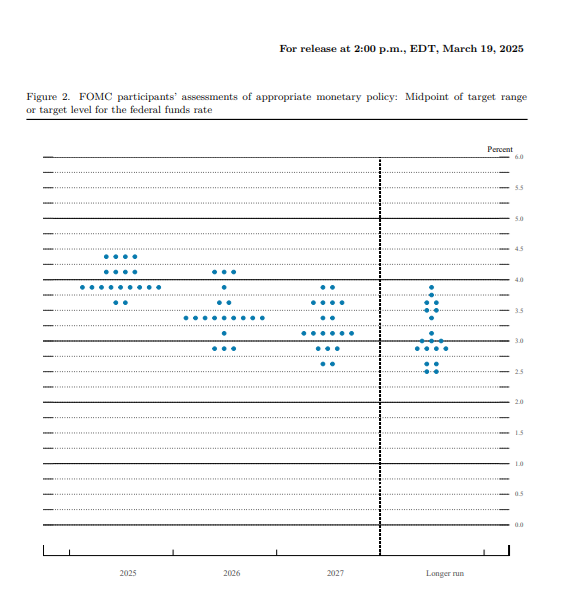

In fact, the FOMC took it even further which is what made this FOMC meeting into a complete farce. Its “dots” at first seemed to be slightly more hawkish as an early bulwark against that potential inflation, but nope, such would require taking some small position on the matter. The relatively higher dots compared to March should be understood as being, well, nothing:

I think what you see people doing is looking ahead at a time of very high uncertainty and writing down what they think the most likely case is. No one holds these rate paths with a great deal of conviction, and everyone would agree that they’re all going to be data dependent.

Perfect. Whether Powell meant it or not, the Fed Chair fairly undermined the whole purpose of this spectacle. He appeared to the public not as the all-powerful Oz, rather the shabby little guy from behind the curtain.

He told America the economy will probably weaken, but not too much because it hadn’t gone farther yet. Powell said prices are going to be rising since everyone says so. But the official response is to not respond – even the dots were shifted not on those inflation worries, they were lifted back to where they had been previously, as a way to express

The Federal Reserve is supposed to be staffed and led by people who are proficient in money and economy, therefore are in a position to offer clarity and guidance. As you can hopefully more fully appreciate, Powell and the FOMC offered the exact opposite because that’s what they have always had. They gave the waiting world zero to go on because, implicit in everything, the institution itself has zero to offer.

Other than policy rates…

On to more important matters

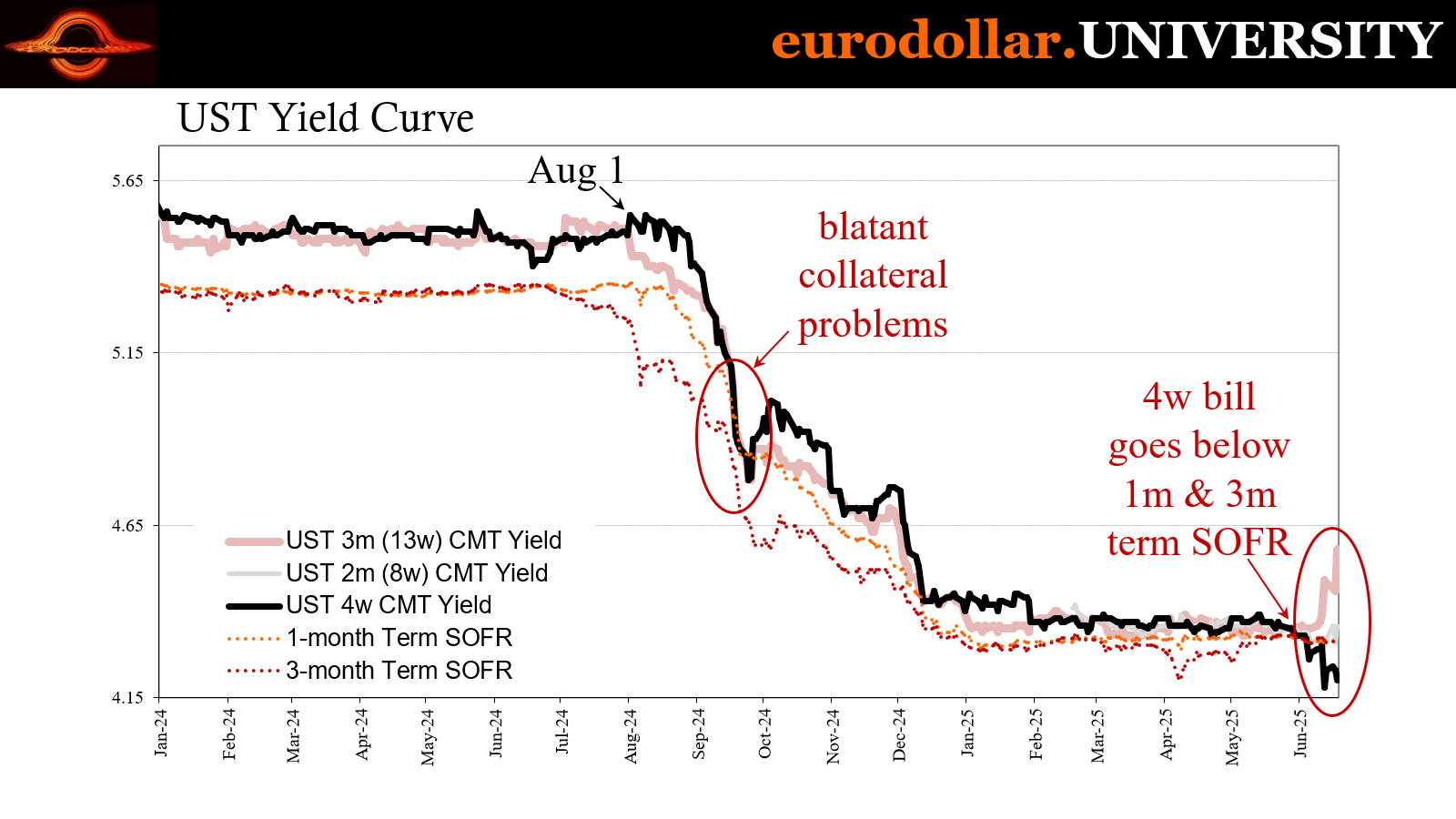

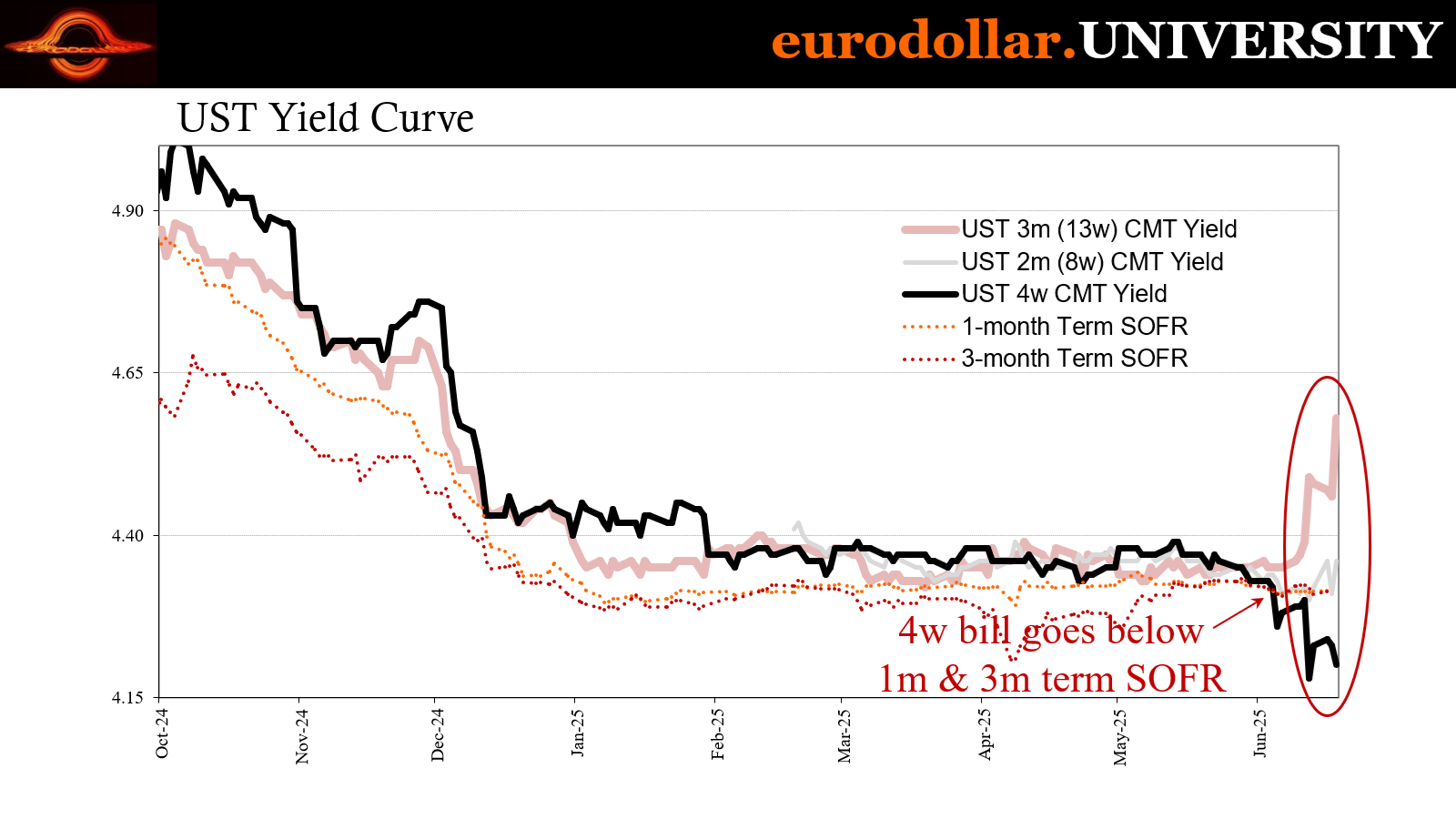

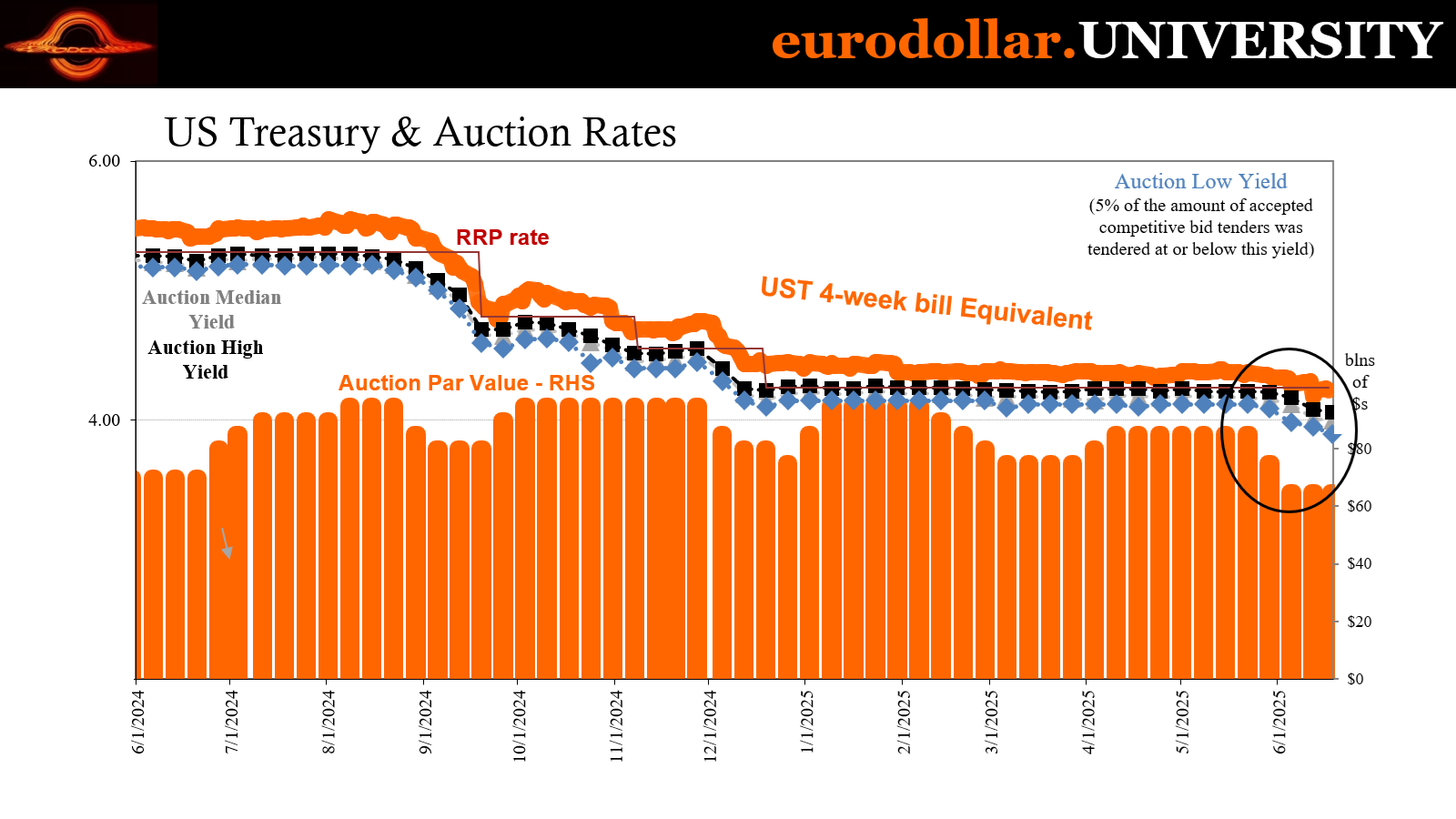

T-bill rates have swung more wildly in the past week as the debt ceiling moves into view. Market participants appear to be zeroed-in on middle August as the point when the government’s extraordinary measures employed this year to avoid breaching the debt limit are exhausted.

As a result, the important 8-week bill (2m) has seen its rate shoot upward. Today’s auction of $55 billion in that maturity saw the high rate soar all the way to 4.47%. As a result, the Treasury Department said the so-called investment yield in the secondary market jumped to 4.58%. That’s nearly a quarter-point rise since June 6.

To review: MMFs (mainly) will avoid any maturity of bill which might fall near or just past the estimated X-date, the day when the extraordinary government measures are no longer sufficient to keep the feds in compliance. The fear is should Congress and the administration somehow fail to raise the limit there is the small chance a specific bill which matures around then could face delayed repayment. Given mark-to-market constraints, MMFs might be forced to “break the buck” after marking down any affected instrument (for this probability).

So, they avoid them entirely out of an overabundance of diligence.

When doing so, it distorts collateral to an unknown degree. If the market begins to avoid the key 8w maturity because of price volatility, that can reduce the availability of one top collateral flight.

As a consequence, demand for other bills typically rises and we see that at the 4w. Moving opposite its cousin, the other bill today yields just 4.20% following its auction of $65 billion which produced a high rate of only 4.06%. I had already pointed out how, before all this, the 4w yield had been moving lower and had, in fact, breached the RRP “floor” (briefly) back on June 5 before this latest debt ceiling matter came about.

While its current drop is more clearly related to the avoidance of the 8w, we do have to keep in mind the 4w yield was lower to begin with based on fewer of those bills being issued along with that other as-yet uncorroborated demand factor (read: collateral).

Moving ahead, another debt limit episode risks another form of possible collateral disruption to go along with the pullback in bill sales. Should the summertime economy reignite similarly to last year, maybe more, collateral could be a possibly amplifying negative compounding a volatile financial situation.

What if this had come up last summer? As it was, we saw collateral conditions quickly devolve to the point the 4w bill yield was falling fast, eventually even getting under comparable rates (like term SOFR) by mid-September. Had there been fewer bills issued then plus problems with some of the maturities, like the 8w currently, all that surely would have escalated all those monetary difficulties at a particularly weak spot for the markets and the economy.

As the debt ceiling drama plays out – again – we’ll be keenly watching the bills and other factors. For now, this is just where everything stands at this early stage.

For all the fixation on Fed dots among the mainstream and what they allegedly mean, last June the FOMC’s graphic had the majority penciling in at most a single rate cut for 2024 – and that was already halfway through the year. For 2025, those same dots had roughly 100 bps in cuts. In other words, officials last June were an entire year off. Their 2025 projection ended up happening in 2024.

Another reason Oz is loathe to commit.

Though the Fed is perceived to be hawkish relative to everyone else, and they are, it was still forced by circumstances to accelerate the presumed trajectory of cutting anyway. Jay’s right in that the dots don’t mean anything, though very wrong about why.

He says it’s because the Fed has nothing to offer anyone about the state of the economy today or tomorrow, not even a modest guess. Again, what would you say you do here?

Ben Bernanke’s Nobel Prize for playacting must be rolling over in its grave.