SLR IS NO GOSSIP

EDU DDA Jun. 25, 2025

Summary: Ever since the basis trade blowup, even before then, government officials have been mulling a change to the SLR. This is the Basel 3 rule which primarily governs bank capital and has been advertised by regulators as a possible fix to “Treasury market liquidity” in times of strain. If they don’t then immediately add the term “repo” to any plan, you know not to take it seriously. But who did it come to be this way? Today’s DDA looks at what’s happening now, the dives deep into the story behind it.

GLOBAL LEDGER MONEY IS NOTHING LIKE TRADITIONAL FORMS. THE EURODOLLAR DIDN’T JUST CHANGE THE FED, IT CHANGED BANKS AND, EVENTUALLY, BANK REGULATIONS.

There were rumors and even a report, not confirmed, last week that the bank regulatory triumvirate of the Fed, FDIC, and OCC had come to an agreement on the SLR matter. The issue has been tangled up in the basis trade malfunction, another symptom of authorities looking in the wrong direction and crafting “solutions” that, at most, might help clean up the mess after the mess got created anyway.

But rather than simply exclude Treasuries from the SLR calculation, the proposed rule change just lowers the charges altogether (I’ll explain this in more detail below). It’s a lot of shuffling around for what is functionally irrelevant. This is one of those areas, like the Fed’s interest rate policy, where there’s massive sound and fury for the sole purpose of being seen that way.

How many regulations can we fit with the angels on the head of a pin?

The more important question is, how did it get to be this way? There is, as always, a lengthy story which does uncover not just the origins, also why, in the beginning, this all made some sense – even if not long later it all took the wrong steps and direction. Like the Federal Reserve being forced to the sidelines to endlessly hype its interest rate lever, the eurodollar also forced bank regulators to basically come up with a workaround.

Today’s DDA is split into three broad parts: first, the background for the current case. Second, what the most recent developments are now that we have confirmation on what form the reform is likely to take. Finally, the historical backstory behind where all this nonsense came from and why.

The cliff that wasn’t

In the early days of the pandemic, the three stooges decided to temporarily exempt Treasuries and also bank reserves from the calculation. They reasoned a lower balance sheet “cost” for those would first create an incentive for covered banks to buy lots of the looming bond deluge after the CARES Act ramped up.

Plus, with the Fed’s QE on turbo, officials didn’t want the flood of bank reserves unleashed by it to in any way dissuade institutions from engaging in riskier lending and other activities – like money dealing – the system was going to need, too.

Thus, it made (government) sense to temporarily change the SLR, exempting the above assets for a period of one year.

The Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) was invented in 2014 as part of Basel 3, so you know its purpose straight away was and remains trying to clean up after Basel 1 and 2’s regulatory rules spectacularly failed (more on those below). The SLR forces banks to hold capital against all its assets, including those off-balance sheet or where the firm has some partial exposure not otherwise captured by pre-existing metrics.

And, most importantly, unlike prior capital ratios there would be no weighting; all assets were treated the same so banks couldn’t effectively hide leverage in regulatory capital relief any longer. Whereas Basel 2 considered a Treasury (or equivalent asset, where the prior rules were easily gamed) very differently from, say, a low-quality mortgage loan, Basel 3 wouldn’t care what the loan or bond was, they’d all count the same and mean the same capital requirement no matter what.

It was a somewhat understandable overreaction given the shortcomings of the previous rules.

So, you can see why there is this idea that the SLR may constrain bank activities. The more a bank does, the more assets go on the balance sheet, the higher the capital irrespective of what the asset or activity might be. Back in 2020, authorities didn’t want to take the chance the SLR might create a binding constraint. They changed the rules if only temporarily, intending to change them back in early 2021, which the trio of agencies did.

Many of the usual “expert” commentators at the time (2021) were concerned this created an SLR “cliff.” Loaded with Treasuries and stuffed with (inert) Fed bank reserves after a year in the early pandemic/lockdowns, suddenly reimposing a binding capital constraint threatened to lead to a stampede out of Treasuries (banks couldn’t and can’t do anything about the Fed’s reserves). They’d sell, sell, sell rather than take the capital hit, or something.

Even if you aren’t familiar with the episode, you probably already know what happened. As usual, not a thing. There was no rush to sell, there was no cliff. The SLR came back and hardly anyone outside the Fed, FDIC, OCC, and their compliant media noticed. The markets sure didn’t care.

Bankers weren’t happy, of course, they never are when balance sheet costs are raised for any reason. Still, there was no trace of anything. All the evidence you need to reach that conclusion is how the SLR cliff easily faded into a tiny, trivial footnote in bank history, nothing more.

The official splash

I covered the Treasury Department’s preferred approach to the “Treasury market liquidity” problem, as the government saw it, anyway, here. Remember, this is all mainly a reaction to the basis trade malfunction which was itself triggered by a deflationary monetary shortage in repo (for which we just went over some of the stats and evidence from TIC).

The thinking, quite simply, is that if Treasuries are again exempted from the SLR then dealers will be more likely to buy them when the market is experiencing duress and stressed selling as in April. Secretary Bessent claimed the administration was working on that plan, and did so as a transparent means to calm anyone in the public who might be questioning the safety of the Treasury market (rather than more appropriately why there were deflationary monetary conditions to begin with).

However, Treasury doesn’t get to say what the bank rules are, the stooges do.

Bloomberg reported last week the triumvirate was going to take a slightly different direction. That proposal did not exempt Treasuries, though it did seem to lower the calculation in its entirety.

This was confirmed today, and is a reduction in both the eSLR (applicable to large globally systemically important banks, or G-SIBs) as well as the regular SLR placed on others.

The proposal would lower a bank holding company’s capital requirement under the eSLR to a range of 3.5% to 4.5%, down from the current 5%, according to the people, who didn’t want to be identified discussing nonpublic information. The firms’ banking subsidiaries would also likely see their requirement reduced to the same range, down from the current 6%, the people said.

The Fed’s Vice Chair for Supervision, Michelle Bowman, released a statement (via CNBC):

The proposal will help to build resilience in U.S. Treasury markets, reducing the likelihood of market dysfunction and the need for the Federal Reserve to intervene in a future stress event,” Bowman stated. “We should be proactive in addressing the unintended consequences of bank regulation, including the bindingness of the eSLR, while ensuring the framework continues to promote safety, soundness, and financial stability

Like the Fed’s interest rate lever, the SLR or the eSLR just isn’t a binding constraint no matter how many times anyone repeats the lie. In fact, the best comment I saw came from Bloomberg, of all places, which undercut the whole thing, especially given who it was who made it:

“When regulators temporarily excluded Treasuries from the leverage ratio in 2020, most banks chose not to take advantage of this exclusion because doing so would have triggered restrictions on their ability to pay dividends and buy back shares,” [said Jeremy Kress, a former Fed bank-policy attorney]. “This experience suggests that if banks get additional balance sheet capacity from leverage ratio changes, they’re more likely to use it for capital distributions to shareholders rather than for Treasury market intermediation.” [emphasis added]

That one made me smile. I know it’s among the driest humor that exists, still this exposes the performance art beyond “bank regulation.” Banks operate on vastly different considerations than how governments see them. These ratios and estimates are nothing more than press relations intended for public consumption, not effective solutions to very real problems.

After all, when it comes to the basis trade or “broken” Treasury markets, no one ever says “repo.” Once that connection is made, then you know it is finally becoming serious. But that can’t happen until they all finally admit what the Fed really is.

The backstory of the backstory

Like the modern Fed’s, the eurodollar’s evolution changed the way banks operated, so of course it would have to change the way governments attempted to police them. To begin with, there is no money in eurodollar networks except bank ledger money. Prior rules were set up governing physical cash and reserves which increasingly didn’t apply to most circumstances, least of all in any binding way (as Paul Volcker found out in the late seventies).

Much of this government reaction came about during and after that decade. Prior to then, the eurodollar could remain hidden and obscure since no one knew it was out there and it wasn’t creating any visible problems. On the contrary, global bank money was solving Triffin’s “dilemma” and generating massive tangible benefits from increasing globalization and prosperity.

Once the Great Inflation showed up, however, this hands-off approach (once termed “benign neglect” by influential Economist Paul Samuelson) no longer worked. What to do?

As you might imagine, there were a number of new challenges to a common global ledger money currency from the national perspective of various regulating bodies. Moving “dollars” all over the world creates all sorts of potential risks. For one thing, how might disputes be reasonably, efficiently settled? What about monitoring banks on the other side of the world?

Whose job even is that?

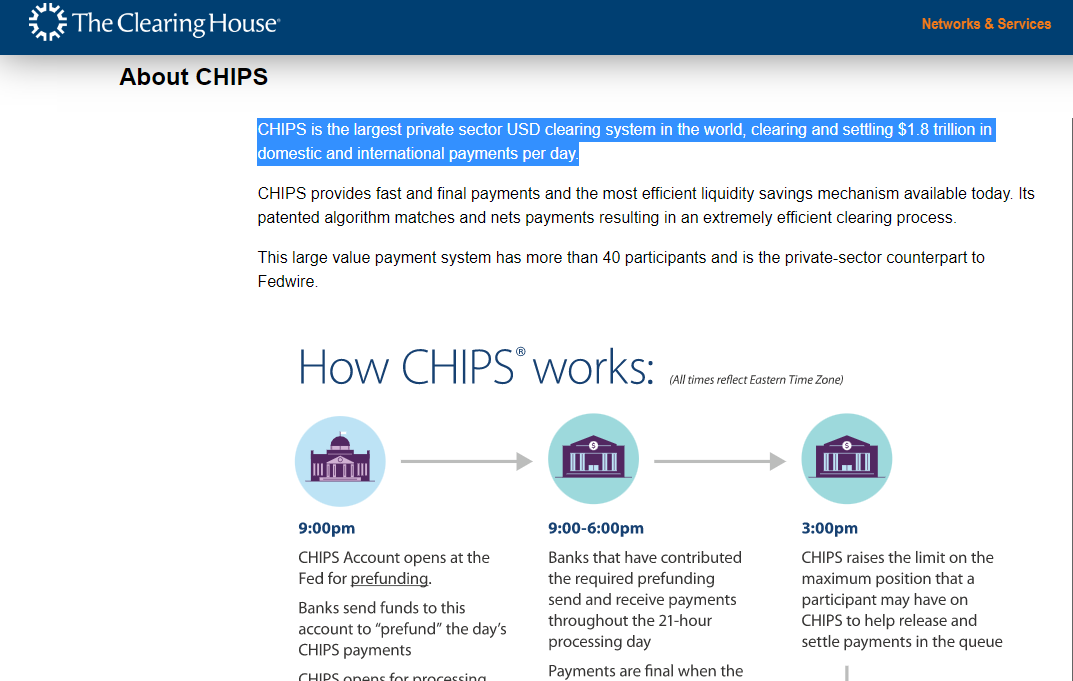

Eurodollar banks had already gone about setting up their own internal frameworks, what today are called financial utilities like CHIPS designed for more than simply clearing payments. Given the international nature of the monetary enterprise, though, it was one thing for members of the New York Clearinghouse Association (the trade group responsible for CHIPS) to sign on to messaging and payments rules. What happens if some government on the other side of the ocean claims jurisdiction?

In those early days (CHIPS was set up in 1970), on an otherwise uninteresting morning in June 1974, we started to find out. On the 26th, a midsized German bank hardly anyone had ever heard of, Bankhaus Herstatt, had been closed by regulators in that country. What made the episode historically remarkable was this one tiny firm’s firm connection to this burgeoning global monetary regime.

Herstatt had been very active in London trading, eurodollars. Not simply taking in eurodollar deposits and arbitraging the spread between offshore and New York dollar markets, this mid-market German firm had become a relatively significant player in derivatives transactions, mostly currency forwards, in dollars.

And these had come to the attention of authorities in England as well as Germany as far back as 1971. In the fall of 1973, Richard Hallett from the Bank of England, according to archival sources, had made direct contact with Iwan Herstatt, the bank’s founder, about what seemed to have become “excessive” positions in the eurodollar market.

Herstatt instead reassured Hallett, claiming various legitimate reasons for such large essentially short dollar positioning.

…[we] had very important Ruhr customers who had entered into large forward contracts with the Bank, which the Bank, in turn, had covered in the market. Consequently, their forward book, though large did not leave them with exposed positions.

Whether this was ever true is still a matter of some debate. Regardless, by promising to pay dollars to these Ruhr customers tomorrow the bank didn’t possess today had left Herstatt open to risks of foreign exchange; not just a rising dollar in the sense of newly floating currency exchange values, but also the less recognizable rising dollar “stuff” which includes a much more expensive borrowing environment (especially controlling forward liabilities).

This gave rise to a ballooning foreign currency liability, as regulators in Germany noted early in June 1974 just weeks ahead of the firm’s final chapter.

Checking through the monthly data of Bankhaus Herstatt, it is striking that the receivables due daily to foreign banks have raised in April of this year by 283[million DM] to reach 589 and in May this year by a further 257 to reach 846; so that they reach a good third of the bank's balance sheet of 2421.

In order to participate in the eurodollar market, Herstatt had opened a correspondent relationship with Chase Manhattan Bank in New York City, not London. This was not a trivial difference, as it turned out, though it always had been in terms of how the market seemed to operate seamlessly.

On the morning of June 26, that fateful day, regulators in Germany were late in gathering to make their final determination. Intending to begin earlier in the morning, local time, a flight delay along with heavy traffic instead had meant authorities wouldn’t finally and officially decided to end Herstatt until 2:40 pm local time. Closing it down would become effective at the close of German trading, 4:30 pm local, which, however, was 10:30 am in the middle of a very much open New York session.

The German government hadn’t given any thought about time zones nor the peculiar quirks (for 1974) of global eurodollar banking and cross-border liabilities that arise from it. Herstatt’s correspondent, Chase, learned immediately of the closure while in the middle of still processing payment requests, on Herstatt’s behalf, through the CHIPS system.

No small issue, Chase quickly figured out that it was sitting on around $620 million in payment requests to be made on behalf of Herstatt – for which, given its closure, Herstatt wasn’t going to be reimbursing back to Chase.

More than mechanical problems

Swiftly taking action, Chase froze the outgoing requests from Herstatt’s account while still accepting incoming payments for it (as a liquidity protection against possible losses). For the first time, international banks became aware of another kind of intraday credit risk due to differences in time (had Herstatt been closed by regulators before New York opened, there wouldn’t have been any imbalance to Chase as correspondent; because the decision was delayed, Chase had already begun the day processing payments on behalf of a bank in Germany that was in the process of being shut down).

Quite naturally, the New York Clearinghouse Association protested. Within a week of Herstatt’s closing, the settling members had introduced a recall provision into CHIPS that would allow them to claw back funds from foreign respondents up to 10 am New York time the following day; thus, undercutting a key fundamental function of these real time gross settlement (RTGS) interbank systems.

If clearing agents could “recall” payments already presumably cleared the day before, were they ever really cleared and settled at all? No. Obviously not.

It was a question that, in the short run, interbank counterparties sought to avoid answering. Over three consecutive days in early July 1974, CHIPS nearly ground to a halt; final settlement deadlines had to be extended to 1 am (ET) on each of them.

Consequently, the system had reached an important systemic crossroads. With CHIPS failing to provide timely processing, the eurodollar market became nearly non-negotiable; borrowing rates skyrocketed, and often funds were unavailable even at quoted prices. The activities of one small bank in German had come to threaten the entire global currency system, even if hardly anyone knew it was the global reserve system.

Understanding just how important, the NYCHA along with settling and nonsettling members got together to work out the kinks. Difficult as it may have been, there was too much business to be done. Better to have to worry about even serious structural problems than to stop everything over mere trivia.

From the outside, concerned central bankers and bank regulators informed politicians they were going to get involved, too. On September 10, 1974, the Group of 10 central banks issued a statement which promised:

To intensify the exchange of information between central banks on the activities of banks operating in the international market and, where appropriate, to tighten further the regulations governing foreign exchange positions.

At their December 1974 monthly meeting, the G-10 central bankers created an informal committee chaired by George Blunden, head of supervision for the Bank of England, which began meeting in Basel, Switzerland, and whose “main objective was to help ensure bank solvency and liquidity” of this new (to authorities) international banking framework. In order to accomplish this, in the wake of Herstatt, they had “to give particular attention to the need for an early warning system.”

How to do so? Gossip.

Yes, you read that right. And looking back with hindsight, this would have been far preferable to what was eventually settled on – if it could ever had been made to work. As stupid as it may sound at first, there probably was a way to do it, too.

Understanding the eurodollar challenge…then failing it

There was simply no way for regulators in one country – preserving national regulatory regimes was declared a priority – to figure out what a foreign subsidiary of a local bank might be doing in another (in addition to Herstatt, 1974 featured a couple other cases, including the Israeli British Bank, which exposed these and other serious potential deficiencies in a global banking environment). The easy way, perhaps the only realistic way, was for regulators to try to coax information, even in the form of informal rumors, out of overseas traders in order to refine a list of who might need further local regulatory attention.

Blunden himself saw few other options:

[T]he only possible and useful kind of international early warning system would result from the establishment of contacts…for the purpose of confidential exchanges of relevant information picked up by their own national warning systems.

This wasn’t a popular proposal. Another of the G-10 committee members, Pierre Fanet, from France’s Commission de Contrôle des Banques, admitted, “it was hard for him to imagine that information based simply on rumors, or even on accusations, could be transmitted to the supervisory authorities of other countries.”

Bankers might not have liked it, who cared? What better way to gain keen and useful insight than from those doing business and intimately familiar with operations. Who else would know of the real nature behind Herstatt’s short dollar book than those on the other side of it? It’s one thing to see a number on a call report or balance sheet statement, entirely different when your own money is on the line below it.

By the eighties, this Basel committee realized trader gossip wasn’t going to provide the basis for an early warning system, they found it riddle with the obvious difficulties. Besides, they were convinced there was another way, an “easier” way. Regulators turned toward more “objective” descriptions which could instead be derived from “legitimate” and immediate (they hoped) data sources; particularly as these could be employed for these increasingly global, increasingly huge, wholesale banks.

Capital ratios and things like that. Quantitative measures.

Not much thought was given to how easily it might be to manipulate such things, unlike, say, confidential information supplied by business counterparties. I’m not claiming the scheme would have been foolproof, only that in theory there may have been far more useful information and therefore actually binding constraint had more thought been given to making it workable.

The eurodollar essentially created an “arms” race of knowledge and information which left governments perpetually behind. They invented all kinds of forms and spit out any number of numbers and ratios, yet never really knew – and still don’t to this day – what any of it actually meant. The gossip system would, at least, have provided authorities with an expert set of guides rather than arbitrarily chosen mathematical guidelines all-too-easily overcome by lawyers, accountants, and derivatives.

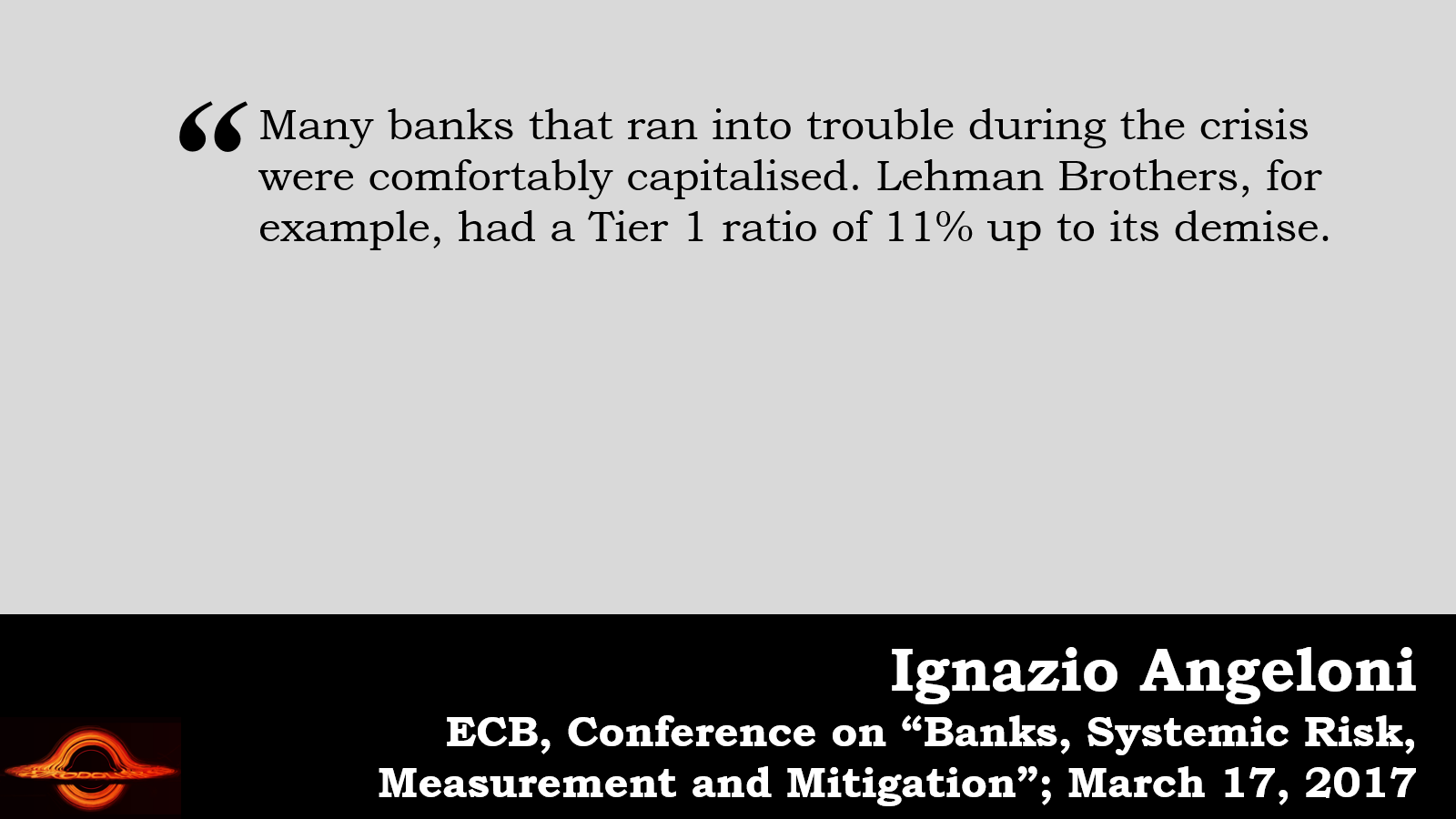

Both Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns sported sterling capital ratios all the way through to their ends. These hadn’t been the early warning system once envisioned. In the mainstream post-crisis opinion, capital ratios were singled out as partly but substantially to blame (for good reason). If banks had learned how to repackage their balance sheet items in order to circumvent these “early warnings”, then simply don’t give them the chance.

Thus had been born, into the post-crisis era of shock over what banks had been doing for decades, the Supplementary Leverage Ratio which no longer weights assets at all.

Is Basel 3 and its offshoots any better?

Ask Credit Suisse shareholders.

The answer to that question depends on what it really means. Better as bank regulation? Not a chance. There is still no serious effort to understand what banks really are and what they do. Authorities continue to treat them as basically 19th century vaults filled with cash. Regulators aren’t just outgunned on information, they’re also terribly behind the times.

Is the SLR better at making it seem governments are doing something important about monitoring and regulating banks? Yep. And that’s what all this is really about. It sounds complicated and important, which is why they all run around claiming that, like the Fed’s rate cuts, the SLR is the biggest factor in the history of everything.

The sad thing is, bankers really do love to gossip.