IT’S NEVER WHAT YOU THINK

EDU DDA May 14, 2025

Summary: With a little more hindsight, we can look back on the events of early April and appreciate them for what they really were: pure liquidations. All the telltale signs were there, now exposed with more perspective. Going back into some of the more infamous monetary events of the past decades provides some insights into two key common elements that very likely still apply to the current case. Even as the financial world cannot re-risk fast enough…because it can’t.

THE FORGOTTEN BELGIAN.

With the aid of additional hindsight, and with considerable recent re-risking, we can more clearly appreciate the depth and violence of early April. Setting aside the specific qualities of tariffs and trade wars, it was indeed a significant global upset. While most focus mainly on stocks, for obvious personal reasons, there were indeed nasty liquidations all over the place, in sectors where they “should” not have been.

Think copper, as a start. The former was driven down more than 30% then bounced back faster and stronger than the NASDAQ had. Given supply constraints on the good “Dr.”, the metal was one of the cleanest examples of pure liquidation pointing to money more than macro driving that downside.

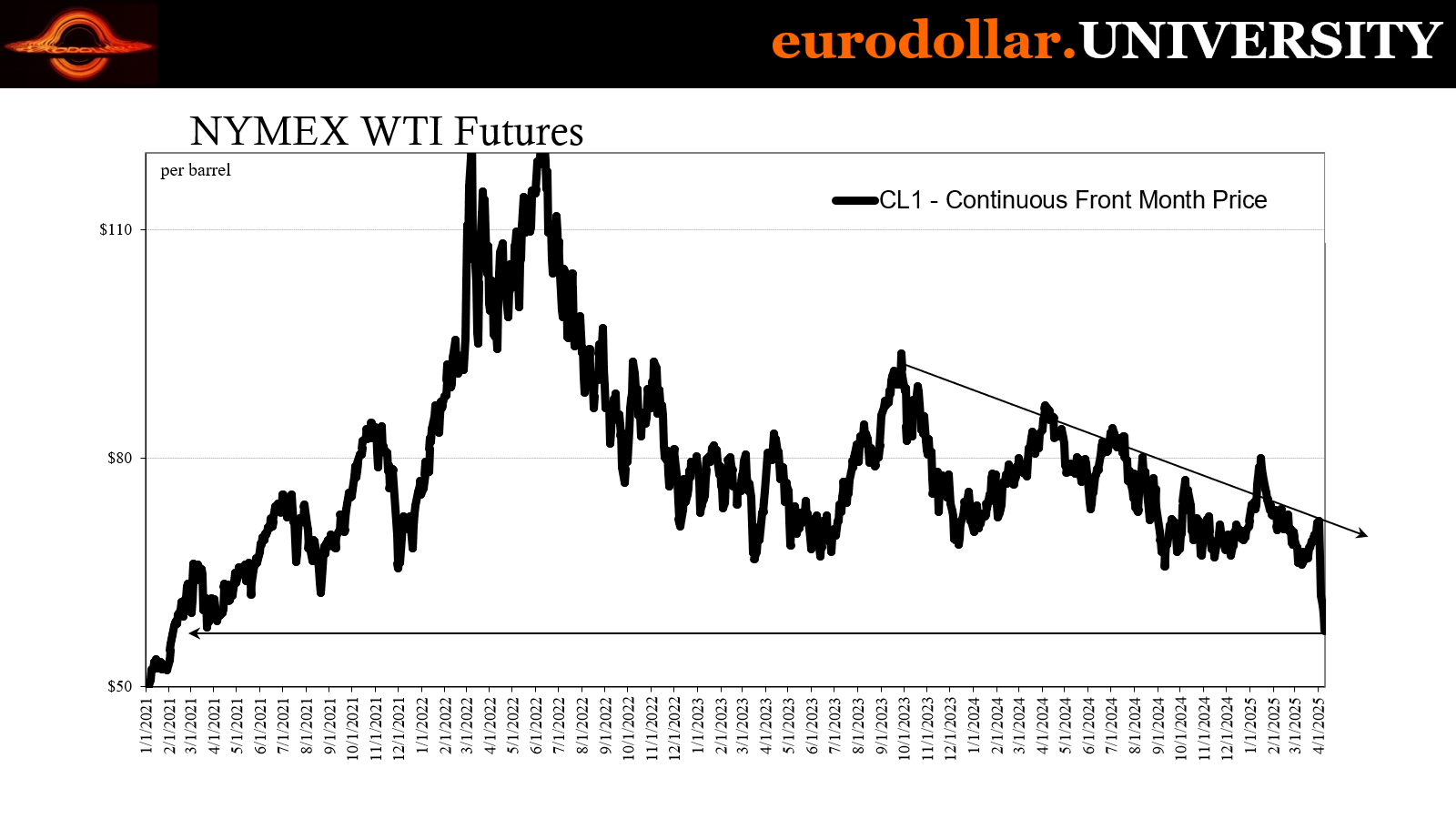

Crude oil, too, not that there weren’t fundamental macro reasons for the swoon. Demand remains a considerable question plaguing the energy marketplace for months prior to recent events (see: weak gasoline), and not only related to China (see: WEAK GASOLINE). Yet, WTI plunged considerably more than weak demand alone would likely have produced.

Liquidations again.

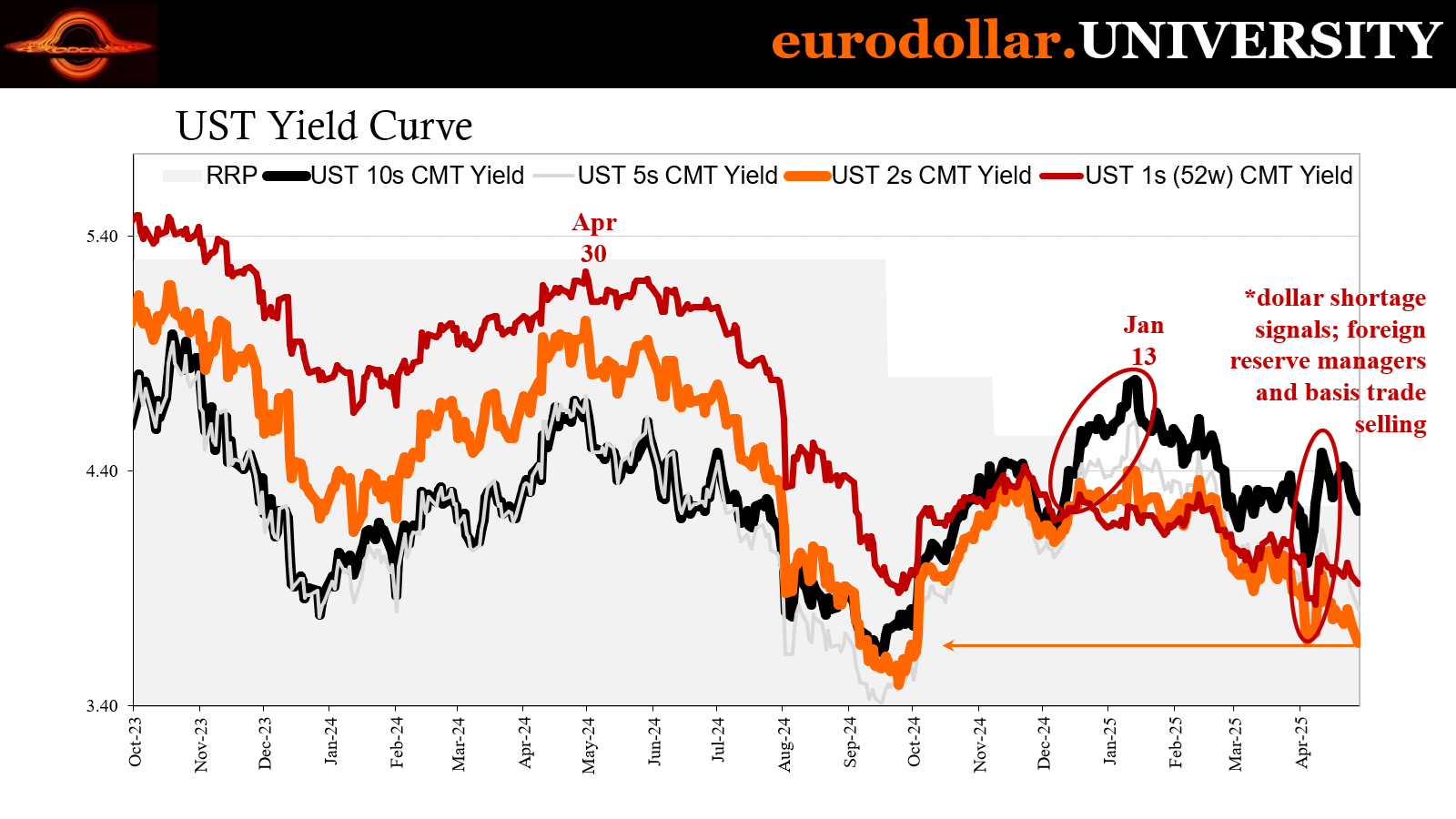

Then there was the basis trade. Mainstream “experts” can and will grouse about a “broken Treasury market”, we know better. Basis trade selling is forced entirely by repo. Given the trade’s set up, that’s the only possibility. There is otherwise no reason whatsoever to sell bonds since it isn’t suddenly credit risk springing up, or some (additional) irregularity in the futures market. The only reason why the big funds were liquidating was because they were either forced to (monetary shortage) or they felt they were in danger of being forced to (fearing the consequences of a worsening monetary shortage already visible in the segments noted above).

While the proximate cause was the abrupt fear over trade wars, such was only the spark. More important even now is what happened thereafter. Liquidity providers stopped providing liquidity which can mean a few possibilities, eventually zeroing-in on collateral.

History has shown how collateral difficulties are more often than not something other than vanilla haircut adjustment on prime MBS. Where liquidations begin really comes from the more complicated arrangements which align with the consensus. It’s the latter part which surprises people, seemingly counterintuitive. After all, we’re meant to presume the most dangerous trades are those which cut against everyone else.

Nope.

To show you what I mean, I’ll go through three examples from history, starting with what may be the earliest collateral-gone-wrong major story.

Straight away, my description perfectly fits with the April 2025 case, even knowing nothing about any specific trades gone sideways. Everyone everywhere was all-in on the soft-landing, which naturally would be why “trade wars” produced such a massive, fast-moving liquidation backlash. When everyone is on one side…

Like a zipper, it all unwinds quickly from there.

Orange warning

On December 6, 1994, Orange County went into bankruptcy with assets that were all still money good (also a common trait, even among the most famous instances like Bear and Lehman). The county’s investment fund, run by Robert Citron, was holding paper from mostly government agencies and even UST’s. Out of the nearly $20 billion in the fund at its demise, $16.7 billion was UST’s, agency fixed rate bonds, agency floating rate bonds, CD’s and commercial paper. The problem was the combination of the floating rate FNMA’s and that the fund was increasingly leveraged as Citron’s bets were further imperiled.

Throughout the early 1990’s, Orange County’s fund was handsomely beating every benchmark. So much so that municipalities throughout the county were beating down Citron’s door in order to invest in his magic; some cities, such as Irvine, even borrowed through bond offerings just to make available cash to put in. S&P, as the bankruptcy transcript tells, even conditioned its highest investment rating on Irvine’s bonds such that they were placed in Citron’s “care.”

The manner of the outperformance was as it usually is in modern wholesale finance; available and easy leverage of all kinds and all forms. In this specific instance, Citron was building the fund’s bond portfolio not for general coupon returns but so that they were available for reverse repos. When the interest rate environment was in his favor, the Orange County fund was leveraged less than 2 to 1; when it started turning against, that was when the leverage piled up as almost a gambler’s view of doubling down to “make it back.”

Everyone was convinced rates weren’t going to move much in ’94, one reason why it is remembered as a “massacre.”

As it turned out, even though Citron’s broker Merrill Lynch had warned him about both the increasing volatility risk of an increasingly homogenous portfolio and that interest rates could rise, Citron continued on his course regardless of the advice (and Merrill kept selling securities to him and funding those positions). Later grand jury proceedings even found evidence that Mr. Citron was using a “mail-order astrologer and a psychic for interest rate predictions.”

Still, the fact that rates had gone up even sharply did not alone produce catastrophe; there were no losses to book based on credit defaults or skipped coupons in any of the underlying assets. The “inverse floaters” at the center of the controversy were simply designed as a mechanism for FNMA to reduce or hedge its own funding costs in the event of conditions just the kind produced by the Fed’s rate hikes in 1994.

The inverse floating rate notes integral to Citron’s strategy for leveraged outperformance were agency coupon bonds that reset them regularly by LIBOR. In December 1993, the fund held approximately $100 million inverse FNMA floaters maturing in 1998, offered in repo to Credit Suisse First Boston as collateral on $100 million funding (I haven’t seen anywhere descriptions of any haircuts, so it may just be or have been assumed 1 to 1). That was not the full extent of the leverage, as the bonds were repledged to total something like 3 to 1 leverage in other funded positions. All told, there were about $800 million in FNMA floaters that spearheaded the fall from grace.

The coupon of the floaters varied inversely to the volatility of LIBOR. The coupon rate is set as the initial payment rate minus some LIBOR spread, meaning that any increase in LIBOR reduces the coupon payments. For FNMA, it is funding protection; for Orange County and Citron, the bonds paid typically a much higher initial rate and, in some cases, might increase (up to a preset ceiling). The lowest possible rate was, conversely, 0%.

Because of this structure, the convexity of the bond is enormous, particularly when compared to the change in value of any fixed rate investment. In January 1993, the coupon on the FNMA 1998’s was 8.25%, but by 1994 the coupon rate was cut all the way to 2.3% and perhaps, via volatility calculations, on its way to zero. That didn’t mean that the bonds would default as they were agency paper, only that the current value of them would fall precipitously with the reset coupons being so far below the “market” interest rate.

Collateral killer.

If there were no leverage involved, Citron’s run as something of a “guru” would have ended but at least not in a prison sentence; it would have continued in underperformance but absent loss as at maturity in every underlying bond principal would have been returned in full. As it was, given the repos, the current values of the securities pledged as collateral matters more than whether those prices actually mean credit losses or not. The more “sensitive” to changes in prices the larger the adjustments that will be made as volatility rises.

For Orange County, the floaters that were pledged in repos meant collateral calls and then eventually collateral seizure when prior demands for additional collateral were not met. Bankruptcy was the only means to stop the seizures (it was alleged), and even then, banks viewed it within their rights to liquidate at current prices, no matter how low.

Thus, the huge losses for Orange County were really produced because the fund could no longer fund itself; once liquidated, the assets were about $1.64 billion less than total liabilities including the nearly 3 to 1 leverage employed near the end. For the overall fund of $20 some billion, even then $1.64 billion isn’t necessarily fatal except that the underlying “equity” was just $8 billion.

Like we’d see with Bear Stearns, Lehman and AIG, collateral shortfalls deliver the fatal insolvency.

Belgium in the aftermath

In October 2011, Dexia’s Chairman bristled at the characterization. His was not going to be a “bad bank” as many in the financial media had been saying. Pierre Mariani, chief executive, preferred instead to call it the “residual bank.”

No matter the label, the firm was being bailed out for the second time by the Belgian government in combination with French authorities. Any assets which could be sold at a reasonable (meaning not terrible) price would be. There were already investors lined up for the pieces of Dexia’s balance sheet unencumbered by stupidity.

What someone might call “reach for yield” in later years, banks across Europe - not just Dexia - came out of 2008 seeking to grow their way back to glory. The combination of a zero-risk weight on sovereign debt, applied at that time also to bonds issued by Greece, Portugal or Italy, plus higher returns drew these already-troubled firms like moths to flames.

Desk managers in them knew these exposures were risky, and therefore had to be hedged. That wasn’t the stupid part. No, the really mind-boggling part of the story was how: Dexia, in particular, used longer-dated derivatives. Called total return swaps, the bank sought, essentially, to short German bunds (as the swap benchmark) as protection against a rise in interest rates.

Contrary to 1994, that was the widely consensus. Consumer prices were rising, along with a potential rapid recovery in the economy, even if delayed a year, would mean rising interest costs p and down the curve. Or so it was presumed.

A lot of times the instruments Dexia used get marked and priced against the US dollar exchange value – which is also always expected to fall in most baseline recovery models. You can already see where this s going.

The bank’s strategists (read: econometric models) never conceived or at least downplayed the scenario where Greek bonds would fall in price, the scenario requiring the hedges, but that German bunds would go in the other direction.

The primary risks, as almost everyone saw them, were how if interest rates rose (and bond prices fell) it would be because of economic recovery, in combination with higher inflation and eventually short-term rates as the world would surely normalize following the Global not-Financial Crisis. In that case, the swap hedging would’ve worked flawlessly.

But that’s not what happened, obviously. Therefore, what were cash-flow positive long-dated derivatives marked in-the-money suddenly became money pits. Once the bank was downgraded in March 2011, because of its riskier sovereign holdings, funding problems were greatly amplified by these “hedges” turning dead set against the bank at the worst possible time.

Once the collateral calls pile in, that’s it. Unless your buffer or margin is enormous, there’s no stopping the downward spiral. At the start of 2011, Dexia held only €21.8 billion in Southern European bonds, mostly Italian. Like Citron’s credit risk-free holdings, it didn’t matter for Dexia, either.

THAT’S IT. WHAT SEEMED LIKE A RELATIVELY SMALL POSITION TURNED THE BANK INSIDE OUT AND NEARLY BROUGHT DOWN GLOBAL BANKS FOR A SECOND TIME IN THREE YEARS.

Despite cutting its balance sheet following 2008, despite reducing its reliance on short-term wholesale funding (a lot of it in dollars, of course) after its first bailout, it was forced to post an additional €15 billion in margin and collateral up to October 2011 on its total return swaps. The more German yields plummeted (as the world was plunged back into an impossible recession), the more the collateral calls, the closer to the end.

Mr. Mariani’s “residual bank” would consist largely of those obligations. It’s not that the investments proved to be bad ones, necessarily; in rough terms because of the way they were structured they cost more to fund than they yielded in returns. That’s what volatility and/or modeled uncertainty will do to pricing

It should be pointed out the role of gain-on-sale-accounting here; the profits of these trades are booked at inception, leaving the bank to write down, if necessary, any other-than-temporary charges if either the market prices or the modeled assumptions change substantially. That’s one reason why volatility is such a killer in terms of funding; a profitable trade booked years before suddenly requires billions in collateral and an increasingly unknown probability of write-downs.

That’s why the “bad bank.” Move that uncertainty, funding and pricing, over to a balance sheet which can withstand those huge negative pressures. In Dexia’s case, the bad bank balance sheet came too late and consisted of whatever was left after everything else had been sold off – this residual bank supported by its existing shareholders, by that time mostly governments in Belgium and France.

The role of Dexia’s demise in Euro$2 is one of those underappreciated facts, a major disaster in its own right yet standing against an ocean of monetary difficulties.

Whaling on Thames

The next year after Dexia, an even bigger name got itself into the same kind of trouble, if not exactly the same. Unlike Dexia, it didn’t lead to the firm’s bankruptcy or takeover, though it did end costing the bank enormously and, for a time, had much of these opaque markets seeing massive opportunity while sitting on the edge of everyone’s seats hoping it didn’t spread.

The bank is JP Morgan, the incident the once-infamous London Whale.

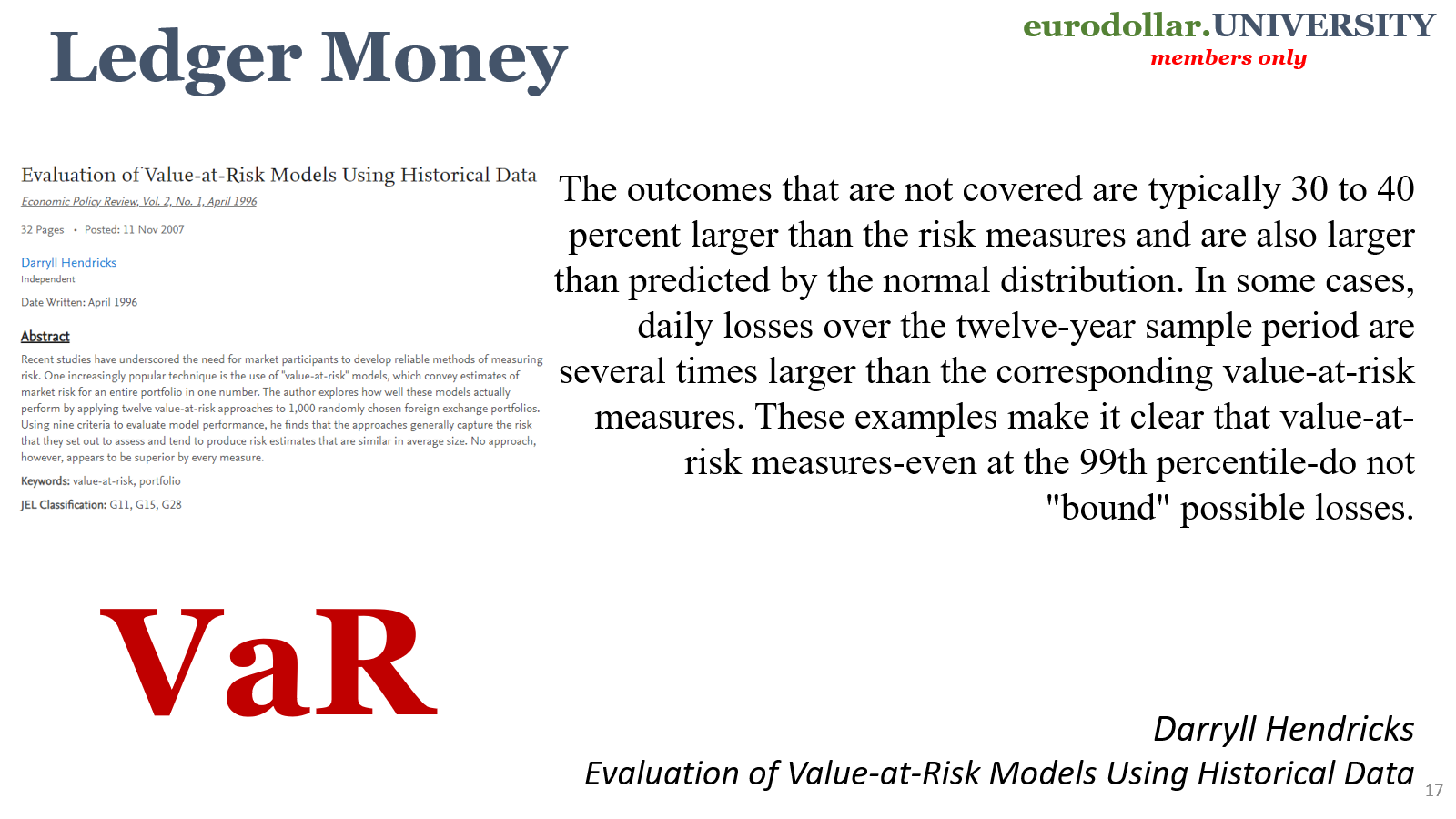

JP Morgan’s CIO unit was developed only to make the bank money in prop trading. The institution had $350 billion dedicated to the unit in 2011 and about $50 billion of that in a synthetic credit portfolio in Q4 of that year. By Q1 of 2012, the very next quarter, the synthetic credit portfolio had ballooned to $157 billion. All of it was governed by complex mathematics, including VaR and especially RWA (risk weighted assets, a very hot topic at the time due to Basel rewriting).

While the basis of the London Whale problem propagated along a credit index called IG9, the last on-the-run CDX left after the panic, it was truly all over the place.

The problem really started in early 2012 when “a significant corporate issuer”, the term JP Morgan’s own internal report uses, defaulted. The CIO’s synthetic credit portfolio was not well enough hedged to withstand that kind of “jump”, an unmodeled tail risk VaR practitioners had been warned about ever since LTCM. According to the internal report, management directed the trading desk and unit to further correct for any weakness by searching and buying “jump-to-default” protection.

Unfortunately, such a move requires artful association and management of correlation, which is often treated instead as a purely mathematical assignment even though 2008 was a veritable flood of just such bad correlation math. Ultimately, the London Whale grew out of that element, as IG9 became the centerpiece of the mitigation strategy. The idea, as with so many of these highly complex FICC activities, “bond trading”, is to simultaneously engage long and short positions but with a heavy gaze upon gammas and tranches (and gammas of tranches).

This is called dynamic hedging. Yep, more hedging. A more honest characterization is leverage. A hedge that makes money rather than recoups losses is exactly that.

As JP Morgan’s report tells it, by the end of January 2012 the synthetic credit portfolio had accumulated about $20 billion in long-risk tied to IG9 10-year positions, and $12 billion in short-risk 5-year notionals also on IG9. The intent here was not just to balance long vs. short, but also to use the longs to generate premiums with which to buy the shorts.

If the math is wrong - meaning, again, the assumptions - then convexity gets to be just so, what starts out as neutral or even short can turn long far too quickly to manage, with liquidity/collateral difficulties making that management all the more unmanageable. The skew in IG9, the “whale” part, was how the trade made it obvious that the CIO unit’s synthetic credit portfolio was in desperate trouble – the trade stuck out like a sore thumb as it basically advertised arbitrage for anyone willing and able (liquidity and leverage) to bet against it.

Of course, many did take that arb since it was unbelievably clear; the IG9 index was trading so far out of “fair value” alignment with the underlying reference names that the counterparty trades expanded, too. What happened, to simplify, was that correlation was way off in the models, and thus the amount of the IG9 long needed to stay neutral or even close to it was far, far more than anticipated.

Therefore, the London Whale was essentially the CIO desk writing far more swaps (long means writing protection) than the market could readily absorb (balance sheet capacity of everyone else). The more they tried to manage their correlation problems, the more the skew on “fair value” of the index to underlying and thus the more firms could bet against what they were trying to accomplish.

The reason they were forced into that position, pinned to the trade as it were, was VaR and RWA. They needed to be neutral in order to not violate their risk covenants, even though (or because) they did already some 300 times. The math became, quite literally, a huge and numbing loss. As it was, the unit was already in talks with management about reducing its RWA footprint since the CIO directive absorbed a huge amount of the RWA “budget.” The last they could afford was to be both losing in terms of profit and violating the math across several dimensions.

So they doubled down again and again and again, in the vain effort to restore a hedged balance. In this specific case, had there been more dealer appetite and balance sheets on offer the London Whale might never had stuck out so far as the CIO unit and its synthetic credit portfolio demanded a correction from its bad correlation math.

OK, but why did all this happen? The reason the CIO unit got stuck in IG9 in the first place was indelibly basic, and I’ll let JP Morgan’s internal report speak for itself:

In late 2011, CIO considered making significant changes to the Synthetic Credit Portfolio. In particular, it focused on both reducing the Synthetic Credit Portfolio, and as explained afterwards by CIO, moving it to a more credit-neutral position. There were two principal reasons for this. First, senior Firm management had directed that CIO – along with the lines of business – reduce its use of RWA. Second, both senior Firm management and CIO management were becoming more optimistic about the general direction of the global economy, and CIO management believed that macro credit protection was therefore less necessary. [emphasis added]

JAMIE DIMON, ca 2012 AFTER LISTENING TO BEN BERNANKE

It was, at its heart, a bet on the recovery – and the firm got crushed, spectacularly, in doing so. In JPM’s case, yes, QE played a key role in the decision-making. Thank the Fed and thank Morgan’s post-crisis “fortress balance” sheet stuffed with collateral it didn’t turn into something more. After the experience in 2011 with several European banks (including Dexia) so soon after the Big One in 2008, can you imagine a major liquidity problem at JP Morgan?

Yeah, me neither. No one would have been able to.

As the world re-risks so heartily on the premise of trade deals, it stands in stark contrast to the liquidation-induced cliff-diving in early April. The widespread and obvious liquidations point to more than the usual risk-off attitudes.

To be clear, I’m not saying there were nearly some outright failures among institutions like the two examples above, merely that this is how the financial system really works down the inside and even if highly-leveraged trades predicated on bad assumptions and questionable collateral availability don’t imperil firms, they can create a mess for the entire global marketplace nonetheless.

What we can take away from the lessons above, on top of so many others like Bear or Lehman, is that there is guaranteed to have been an overwhelming application of complex leverage predicated on the consensus side, which right now still happens to be soft-landing-disinflation-Jay-Powell-is-right. In 1994, Orange County was hardly unique over expectations for low rates. Everyone agreed with Dexia and saw no way in which German bund rates could possibly go lower than they were at the time. JPM never doubted the more optimistic credit derivative math in a recovery everyone kept expecting - which never really did show up (therefore Dexia’s fatal mistake).

This might, then, caution some of that re-risking currently underway should another bout of anti-consensus thinking arise in the near-term. In other words, another challenge to the soft landing would almost certainly squeeze leverage right out of everything, creating problems for derivatives, collateral and collateralized derivatives. Trade wars reignite, or R-word confirmation in macro data independent of tariff considerations.

That is, unless the financial system had a total change of heart, having been busy since April 9 unwinding its leverage and collateral positions to make them less prone to vol. Somehow, given the latest performance from stocks, junk credit, and range of other asset classes, I sincerely doubt this.

After all, there has been so much built up over the past two years on the soft-landing premise, actually trying to unwind it might instead create another London Whale.

That’s one more thing on oil. Right now, even as WTI has come back from its lows, it really hasn’t all that much. Crude stands in stark contrast to the euphoria gripping everywhere else. This time, what’s holding it back are fundamental macro more than any monetary concerns. But in this case, a repeat of that macro challenge might quickly devolve into another liquidation episode, demonstrating the risks of a recession case are more than just some layoffs.

Of the kind right now underway in Canada and the UK…

THAT’S NOT MUCH OF A COME-BACK…