TIC AND A LOT MORE

EDU DDA Apr. 23, 2025

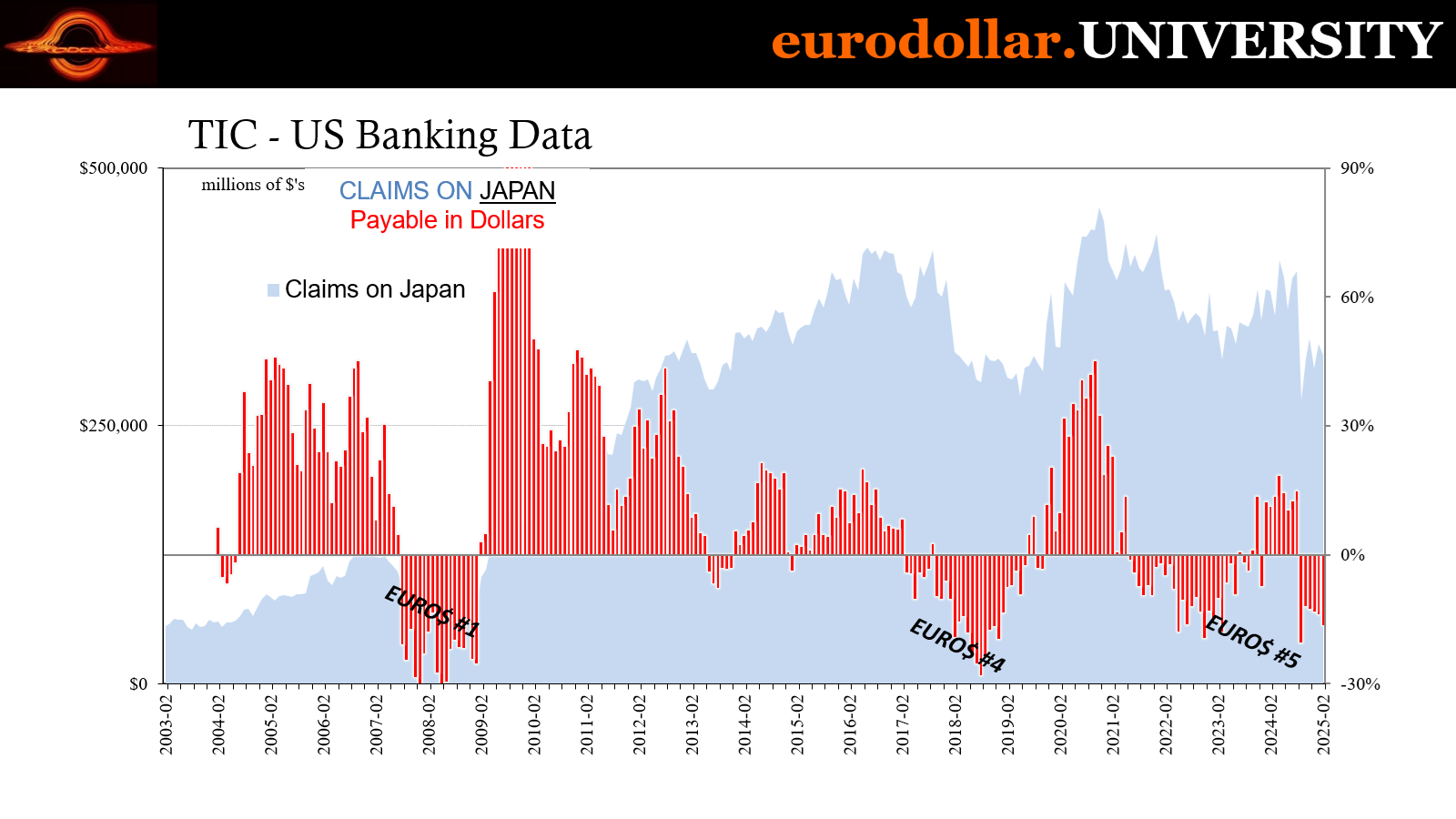

Summary: More from TIC. Deflationary signals deepened in both central eurodollar nodes, Japan and Europe. First, we begin with a lengthy historical review of both if to better illustrate how interconnected the world has been for as long as it has. In fact, the Japanese were the first documented sellers of Treasuries in order to fill in a eurodollar funding gap all the way back in 1963. With that context, the current TIC lending stats point to the same if larger and more global for 2024 and worse during the first two months of 2025. And that deflationary view is reaching multiple angles and dimensions.

YES, GOVTs SELLING TREASURIES TO MAKE UP FOR EURODOLLAR SHORTFALLS GOES BACK A LLLLLLOOOOONNNNNGGGG WAY. ALSO, YEAH, THE FED KNOWS ABOUT THEM.

Going back to TIC one more time for confirmation of other pieces of the global monetary puzzle, at least how it appeared in February just prior to the volatility leading to those serious and systemic bouts of liquidations. We’ll start with Japan since the Japanese find themselves in the middle of practically everything. Contrary to maybe what those unfamiliar with the eurodollar might expect, this is nothing new.

Tokyo had been one of the earliest adopters of eurodollar access and its methods, to the point that some of the first documented episodes of foreign governments (or reserve managers) selling Treasuries to make up for a eurodollar shortfall come from Japan. The latest TIC through February 2025 spotlights Japanese dollar access once again.

Next, Europe. The very namesake of the eurodollar has seen the same as Japan, no surprise. What may be, however, is how ECB officials unlike their counterparts in other places, including DC, refuse to play the “inflation” game or choose to overemphasize the euphemism “uncertainty” in place of honest assessments. It’s still there, just not guiding actions.

That, too, fits within the TIC data setting up into the Spring of ’25.

Lastly, with all that deflationary global money in comes more macro data showing deterioration in sentiment isn’t limited, nor is the growing downside restricted to raw emotional confidence. Still, the confidence data inspires less and less especially in light of monetary and financial backdrop discussed here.

The world is and has been far more interconnected than it is given credit for, largely due to Economists who practice a rigid ideology rather than an honest discipline. And it was made so from the earliest days in large part because of Japan’s unique circumstances. Thus, when something pops up in one part of the eurodollar, we know there will be consequences to some extent basically everywhere else (keep this in mind when going through TIC).

For those who might wish to skip the admittedly lengthy background coming next and get right to the current events, simply scroll down past the next section to the one just below it.

Interconnected from the beginning

The earliest case of a government selling Treasuries (bills) I’ve been able to find comes out of Japan. This isn’t really surprising owing to how the Japanese saw the eurodollar as a way to rebuild their economy quickly following WWII’s devastation and subsequent global mistrust. It was just as convenient of the growing export economy as it was the rest of the world struggling with Triffin’s dilemma.

Eurodollars used to be an answer to a lot of global problems. Nowadays, if not specifically their cause, then an immediate and telling response to those.

Long before today, the Japanese hadn’t just embraced the eurodollar’s world, they began to master it to the point the industrial powerhouse aimed to share dominance over global money; the biggest share of it outside its dollar denomination. There was a time when the euroyen was completing all the necessary steps to become a strong reserve component (by that I mean real reserve currency functions). That’s how intertwined Japan had been from the earliest period.

American retailer Sears & Roebuck pressed Japanese authorities in February 1979 to allow the company to be the first corporation to issue a Samurai bond. These were securities allotted in Tokyo and denominated in yen. The first Samurais had been floated years before, with the Asian Development Bank inaugurating the market in 1970.

The Japanese government had placed stringent controls on issuers throughout that early history. Eligibility requirements were strict, leaving only supranational organizations and other sovereign issues access. Australia raised yen there in 1972, as did Mexico and Brazil. Few others initially followed.

The participation of Sears represented an evolutionary step. The company insisted on the same no-margin or collateral basis it would get issuing bonds in any other major market. The Japanese government had prohibited any unmortgaged bonds within its borders since 1933. Domestic securities firm Nomura Yamaichi lobbied Japanese regulators for a year or more in order to obtain these relaxed restrictions. It was expected to open a flood of demand from other global corporate names.

For Sears, the attraction was simple and familiar to our 21st century experience. Yen interest rates were unusually low. Compared to the rest of the developed world in 1979, money was cheap in Japan.

For Japan’s government, though they may have been reluctant to relax regulations, officials figured it could be worth it if this represented the initial move toward a long-sought goal. There was, almost everyone anticipated, the opportunity particularly during that specific decade to turn the yen into a global currency with the dollar adrift under inflationary eurodollar excess.

Two years before Sears’ Samurai, the European Investment Bank had issued the world’s first euroyen bond. As with eurodollars, euroyen have nothing whatsoever to do with Europe’s modern euro. The term “euro” when applied to a currency simply means “offshore.” Thus, EIB’s 1977 float was a debenture denominated in yen but issued outside of Japan in Europe.

Japanese banks weren’t particularly thrilled over these developments. In many ways, the bond market is a banking system bypass, a competitor of sorts. Japan more than any other country has depended heavily on its banking system throughout its modern history. A virtual credit monopoly, depository firms actively argued against securities firms entering their business, though that business more and more had less to do with strictly Japan.

Banks had to have been very active in offshore currency markets. A consequence of the country’s postwar reality, capital flows were highly restricted. When Japan capitulated to the Allied powers in August 1945, it also surrendered all its foreign assets.

It was left for the government to purchase exportable goods at elevated prices in yen in order to turn around and sell them internationally at whatever lower price could be obtained. On the import side, food and other necessities were bought at whatever overseas costs and then sold very cheaply to a starving population. This subsidization on both sides required huge inflows of foreign exchange initially financed by the United States through the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers (SCAP).

In 1948, however, SCAP ordered the subsidies to be curtailed requiring severe fiscal and monetary restrictions to complete. In later 1949, the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Law was implemented virtually outlawing private foreign exchange transactions, with the exception of large export firms. Japanese residents who obtained any foreign currency were required to immediately sell it to specifically authorized special purpose “foreign exchange banks” operating on behalf of monetary authorities.

Thus, foreign exchange banks would build up over time a balance of reserves in the name of the government but available for wider external use. One of those was the former Yokohama Specie Bank which had been established in 1880 but was reorganized in 1946 as the Bank of Tokyo.

Once Japan was granted full independence in 1952, it became solely responsible for its own current account. The Foreign Exchange Bank Law of 1954 had been created in response to an acute foreign currency crisis (shortage) the prior August. Not only would foreign exchange banks be permitted to more freely engage in those transactions, any that registered with the government under that law would also be eligible to open foreign branches abroad.

For banks like the Bank of Tokyo, originally the only Japanese bank that registered via the act, it was an opportunity to grow in these relatively new offshore spaces. For Japan as a whole, it was hoped this would aid in deepening monetary flow so that its imbalances wouldn’t derail what was becoming a powerful and sustained export-driven economic revival.

Bank of Tokyo would set up offices in London and New York, as well as taking a particular interest in California. The bank even obtained the highly unusual distinction of employing more non-Japanese than Japanese workers.

In 1956, there were about 15 foreign bank offices in operation, all of which belonged to the Bank of Tokyo. A decade later, in 1966, there were 56. By the time the euroyen bonds were being discussed along with the outlines for eventual Samurai bond liberalization in 1976, foreign exchange banks in Japan reported 116 foreign offices.

Therefore, fully entrenched and dependent on global eurodollar conditions, a small hiccup in 1963 forced the Japanese government to step in on behalf of its local access marketplace, a hitch that originated on the other side of the world in Italy.

The Italians in the early 1960s were in trouble. Their currency, lira, or lire, was the sick man of Europe since it was tied to a malfunctioning economy beset by governmental problems along with too many on the private side to count. A real mess.

Normally, this kind of risky proposition would have sent speculative investments as well as legit financing running for cover – and it did. By 1963, Italy’s own rather more traditional balance of payments deficit was thought to be in the neighborhood of $150 million. It doesn’t sound like much today, but this was a huge imbalance and given that it was, anyone would’ve been forgiven for anticipating, even betting on the lira’s collapse.

Instead, it ended up the US dollar suffered the apparent “damage!” How? The Swiss National Bank and eurodollars.

Italian commercial banks had been let to borrow in the eurodollar market in increasingly unrestricted fashion in 1962. They then did; hand over fist. In the first three-quarters of 1963, it was believed these Italian financials had pressed the eurodollar market into lending about $150 million – curiously, the same amount as Italy’s capital deficit and thereby masking it.

So, $150 million, give or take, came in borrowed from eurodollars while $150 million in lira went out to, where? Switzerland, mostly, and a few other places. Outflows in lira forced the SNB to buy up the currency lest it cause Swiss private banks further trouble. What to do with the lira? Sell it for dollars, eurodollars, of course, which pressured the lira and leading to the Bank of Italy (central bank) stepping in to buy it back from Switzerland.

Thus, on both ends, the US dollar was used to support the huge Italian monetary deficit. In September 1963, the FOMC was far from thrilled to find out this fact:

But the dollar has been affected by these movements as the vehicle currency of most exchange transactions: when there are heavy shifts, say, of Italian lire into Swiss francs, the dollar should, in theory, become stronger against the lira and weaker against the franc, so that the combined impact would be neutral. But if, as has actually happened, the Italian authorities intervene in the market to prevent the lira from weakening, the dollar does not strengthen in Milan but it weakens in Zurich--with unfavorable psychological repercussions. [emphasis added]

Once you understand the Fed’s complaint, it boiled down to this: the SNB, for its part, informally rejected Fed overtures that perhaps the Swiss might be better served using their own currency to stabilize their own currency.

Rebuffed by the miffed American monetary officials, the Swiss chirped back that their access to the eurodollar was by every means the best, most efficient vehicle currency by which to resolve monetary imbalances that might arise between otherwise would be completely disconnected and unrelated national circumstances. This was an Italian issue that grew into a Swiss issue ultimately settled by the eurodollar as it more and more dethroned Bretton Woods.

Connecting the world while it did, for a lot of good…and some bad, particularly more of late.

And it wasn’t just foreign banks and foreign central banks availing themselves of dollar-denominated currency floating around by the bushelful offshore; with nary a printed paper Federal Reserve Note in sight among the bushels. On the cusp of what would, just a few years on, become the Great Inflation, the blinded FOMC in June 1963 relayed another evolutionary truth which would come to define an entirely changed world:

The Chairman [William McChesney Martin] said that personally he would be inclined to move modestly toward less ease. He added, parenthetically, that he questioned the use of the word ‘tightness’ at this juncture. Never had he seen a period when there was so much loose speculation with money. The practice of American banks in using the Euro-dollar market was growing all the time. [emphasis added]

Far from American depositories, domestic securities dealers as well as American corporations were more regularly and heavily observed for dollars offshore. The increasing utility of the eurodollar system to serve each and every basic need any global reserve currency must was perfectly evident this early. Here’s the BIS in ’64:

In addition, some lending of Euro-currencies has clearly had nothing to do with international trade; for instance, some US security dealers and brokers have been borrowing in the Euro-dollar market instead of from banks in New York. Incidentally, European branches of US banks have recently been shifting less of their Euro-dollar deposits back to head office than a few years ago and have been lending more to local borrowers, particularly foreign branches and affiliates of US firms.

The eurodollar had everything almost from its origin; financing massive national capital shortfalls, and then the regional consequences attempting to manage or unwind them despite neither being original US$ problems; trade financing for otherwise domestic firms; speculative or “money financing” for also domestic securities dealers; foreign central bank acceptance and availing themselves of its broad purposes. And so on and so on.

This is what TIC ultimate provides for us, a modest and still-too-opaque window into that high level, global integration.

Japan then re-enters our story as sort of a collateral consequence to Italy and Switzerland’s dealings. Still 1963, that November while the US and rest of the world’s attention was focused on Dallas, partly related to the heavy borrowing by Italian banks in eurodollar markets as well as the SNB’s other end settlement strategy, Japanese banks found themselves struggling to roll over $200 million in funding, a large sum for the time.

In other words, one day like every previous day they easily arranged $200 million in short-term financing (there isn’t any record whether it was secured or unsecured, though I would imagine a mix of both) badly needed because the Japanese yen was itself a little too lira-like at the time.

The on the next day, so to speak, that $200 million was no longer offered on the same terms. Too much currency risk or credit risk from eurodollar lenders’ perspective, so they shut it down leaving Japan’s biggest and most reputable institutions impossibly short (thus, why it's called a synthetic short position; they aren’t betting against the dollar, rather a funding mismatch which leaves them with the same kind of risk) a huge dollar burden.

Unwilling to see any eurodollar default posted to the Japanese system, the Bank of Japan ordered its American reserve custodians in New York City to liquidate the same $200 million in Treasury bills being held on behalf of the Japanese government (the responsibility of BoJ). The proceeds from the sale were used to close out the eurodollar short, establishing a precedence that remains, and remains misinterpreted, to this day.

Vehicle currency, sure, but it’s not always smooth and easy. Markets, even reserve currency markets, tend to be lumpy and occasionally problematic. So it was for Japan in late 1963, meaning that these collectively short a mammoth $200 million were bailed out by the central bank liquidating reserve assets, US Treasury bills, to supply the necessary liquid answer (below from the December 1963 FOMC):

It was reflected, however, in transactions in the New York money market; the Japanese government, for instance, was selling U. S. Treasury bills to provide funds for Japanese commercial banks to repay Euro-dollar loans they were unable to renew.

Given what actually goes on in eurocurrency markets, the yen was particularly ill-suited to ever be what the dollar already was. The Japanese government, forever careful and conservative on fiscal and monetary matters (Bank of Japan in later experience obviously excluded), just wasn’t going to let the yen be transformed and transfigured as would have had to have happened if it was ever to become a true global rival; meaning, a euroyen as full alternate to the eurodollar.

But even as that general philosophical constraint would help to impede the wider adoption of Japan’s currency, Japan’s foreign exchange banks were more and more unimpeded. They had developed highly sophisticated networks, invested tremendous resources, and cultivated necessary and cutting-edge capabilities. Their offshore capacities would not sit idle.

Ironically, the euroyen and Samurai bond markets wouldn’t start to take off until just after Japan’s bubble collapse in 1989 and 1990. Again, the reason for that was simple; interest rates. The so-called carry trade, the real one not the thing described in the mainstream, was born as the Bank of Japan pushed yen money rates further toward zero through the middle nineties.

In 1994, euroyen issuance skyrocketed reaching a peak in 1996. In that one year, there were nearly 1,100 issues floated amounting more than ¥6 trillion. By 1999, however, it was nearly all gone. In between, the Asian flu.

Though that particular event is always described as an overseas affair, while that is technically true it leaves out the important part. It wasn’t strictly overseas as much as offshore, as in eurodollars and euroyen.

This all occurred just as the fully mature eurodollar system was itself taking off, at least it was outside of Asia. Thus, if Japanese banks weren’t about to become the center of a euroyen orbit, they could at least fulfill another eurocurrency role as being a primary redistribution point of eurodollars especially across Asia. Though the dreams of a global yen died as Japan’s economy was increasingly mired in the first of its several lost decades, Japan’s banks would end up with an outlet outside of Japan for all their enormous capacities (those that still functioned).

Treasury International Capital, Tokyo

We’re going back to what I used to refer to as the “blue” section of TIC. This was my own convention rather than Treasury’s, merely the color of the charts I would make out of American bank claims on foreigners (foreign claims on American banks, in dollars, I colored red; that’s the nature of the eurodollar world, as US banks noted in the previous section are as rabid borrowers of dollars, too, lent to them from outside the country; American banks borrowing supposedly American currency from non-Americans everywhere else).

Among the blue, we find that domestic banks lending to Japanese firms of all kinds has cratered not surprisingly since last July. The carry trade reverse has seen either: 1. a full and sustained retreat in funding demand as Tokyo reassesses recession risks therefore allocation to risky US$ assets (and the like); 2. Or, dollar providers are edging away from lending on questionable collateral (forcing the FX bypass).

In reality, it’s almost certainly some of both. The fact that dollar lending from America to Japan has dropped sharply to both banks and nonbanks is another critical sign along those lines. This isn’t a specific idiosyncrasy for banks, like some regulatory change for example, rather general risk aversion response the same way as past eurodollar cycles like 2018 or all the way back during the very first one.

Not surprisingly in light of all that deep eurodollar history cited above - which only scratches the surface - one of the first deep eurodollar cutbacks to kick off the Global not-Financial Crisis was American banks yanking funds from Japan right in August of 2007.

TIC shows that type of deflationary response from August of 2024 being maintained right into February 2025, the latest figures we have. It also shows a sizable uptick in lending late in 2023 coincident to the arrival of the global bond rally. This corresponds to CLO activity related to the shuffling carry trade thereby setting Japan up – and maybe domestic banks - for the reversal which followed not long after it started.

Lower risk-free bond rates (Treasuries) cut against higher funding costs (forced by the Fed) leading to the negative carry mismatch which sparked the CLO/leveraged loan frenzy (reach for yield) I documented at several points last year. The TIC balances show American banks were financing much of that fun, leaving both exposed to the recession-fear reverse in August. Presumably – and we’re on steady ground here – the same kind of exposures popped back up by March and April 2025 leaving the eurodollar world in its Japan-sized hole.

Treasury International Capital, Europe

TIC also shows the same thing surrounding European dollar access, though for very different reasons (presumably). Before that, the same figures display just how European-centered the first two eurodollar cycles had been, for pretty obvious reasons. It was German and French banks most heavily involved in “subprime mortgages” financed on eurodollar terms, therefore suffering the bulk of the initial setback.

Almost immediate afterward, the “European sovereign debt crisis” made another repo crisis out of previously unimpeachable collateral. That drastic collateral shortage once again created a continent-sized deflationary dollar hole in Europe’s bank condition, with repercussions felt globally (for all the interconnected reasons exemplified in the history above).

There was still a big impact in Euro$ #3 and then also #4, both not to the same extent as #s 1 and 2. Here at #5, it’s even less for Europe meaning still more an Asia focus, however including Europe in the disruptions.

As cited in the previous section, #5 shows the same split nature as Japan. There was a dollar setback in 2022 leading to the crisis of September and October before then the transition from supply shock upside (price illusion “recovery”) into forgot how to grow recession. The dollar retreat (American banks lending less to them) kept up through early 2023’s bank crisis before promptly turning around beginning that June.

This is the same as when bond yields rose out from their bank crisis depths, meaning moderately reflationary in the marketplace corroborating the monetary flows described in TIC.

However, like Japan’s CLO misadventure, this seems to have been a partial miscalculation. While Tokyo’s banks were motivated by negative carry, the impetus here appears to be (by my analysis) misreading Europe’s economic situation. Having suffered a more visible downturn in late ’22 compared to most other places, not to mention fears over the electricity-price catastrophe in the same year, the funding market may have jumped the gun loosening balance sheet dollars anticipating a recovery of some degree by the middle of ’23.

After all, having missed the worst case for energy prices in the winter, then seemingly dodged more disaster after Credit Suisse, why not bet on a European comeback, or at least against further downside?

The error appears to have been caught in that same global inflection we keep coming back to ever since it showed up: March 2024. February 2024 was the maximum growth rate for that mini-cycle, with dollar lending into Europe slowing down from then onward before contracting more recently.

By July, the year-over-year change was practically zero again. After bouncing somewhat into September, American dollar lending has been slowing, a small annual drop in October ’24 turned modestly more negative in November before then becoming deeply so in December.

That fits with dollar behavior I’ve chronicled since then, too. Let’s also not forget how at this very same time, going back to February last year European banks themselves have been loading up on government bonds, going defensive all their own locally at the same time dollar activity pulled back.

Beyond TIC, Europe

The deflationary consequences aren’t going to be limited to Japan and Europe, of course. The more we see these eurodollar proxies reverse, the more confidence we have in that interpretation as well as the greater that deflationary impulse is likely to be.

While Federal Reserve officials cling to the notion that tariffs are equally likely to be inflationary (assuming “uncertainty” isn’t being used as the euphemism described a few days ago), or maybe something else will be, labor market “tightness” and the Phillips Curve, the monetary conditions aren’t having it.

Nor are ECB officials. While there are these examples of officials having arrived at the same conclusions, it is for vastly different reasons than real money those same policymakers are wholly unaware of. This, however, only strengthens the signals. After all, as the Fed is intent on demonstrating, central bank bias is always and forever on inflation. We’ve seen this in every cycle going back to the beginning of interest rate targeting.

Left to their biases, it’s always inflation. The only time it isn’t is when circumstances are too far gone in the other direction to ignore (and even then they resist; see: below). There have been a number of European statements to this effect, with those gaining more as deflationary fallout shows up in plainly obvious ways across financial markets.

This means the probability of seeing negative consequences in the real economy are becoming uncomfortably high. Therefore:

European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde said US tariffs may be more disinflationary than inflationary for Europe even as more time is needed to fully assess the situation.

“It is very unclear what the net impact will be,” she said at a Washington Post event. “Particularly if there is no countermeasures decided by Europe, I think the net inflation is uncertain at the moment, but probably it’s going to be disinflationary more than inflationary.”

The hedging by Lagade is entirely unnecessary, if expected; she is, after all, a central banker.

More importantly, there is also far more evidence for the economy worldwide being in a far more fragile state now versus any other time in the 2020s, apart from the pandemic and lockdowns. The latest data today from S&P Global underscores that point, starting with the loss of momentum emerging in the services economy.

From today’s Daily Briefing (which also includes the roundup of US PMIs, too):

The HCOB Eurozone Composite PMI declined to 50.1 in April 2025 from 50.9 in March, missing expectations and suggesting that private sector growth is on increasingly fragile ground. While this marked the fourth straight month above the 50 threshold, services slipped into contraction at 49.7, and manufacturing remained weak at 48.7. New orders fell for the 11th consecutive month, and business sentiment dropped to its lowest in over two years. Input and output price pressures eased slightly, but employment stagnated due to weak demand. Germany’s composite PMI slid to 50.2, with modest gains in manufacturing and continued contraction in services. In France, the composite index fell to 47.3, marking the eighth straight month of private sector decline, driven by weak demand and collapsing confidence.

By every single angle imaginable, from eurodollar system to market curves and positions, even to ECB officials not mention decades of monetary history, there is zero reason to expect an inflationary outcome from tariffs. There are deflationary signals in too many central places, those which form the very basis of the global interconnections to begin with.