HEADLESS MOMENTUM

EDU DDA Sept. 17, 2025

Summary: Spoiler: the Fed cut by 25 bps. And though the dots did drop, there was no clear signal from policymakers even as the economy itself grows more not less certain. The greatest source of any uncertainty is proven again to be the Fed itself. The FOMC decision and the materials accompanying it were a fiasco of a debacle. No hawks nor doves, just chickens running around headless. The problem isn’t Beveridge or even unemployment, it’s entirely about evidence for momentum from here on.

THEY ARE AT LEAST BACK IN THE CAN…

FOMC was, frankly, yet another complete mess. If it wasn’t clear before how little grasp these policymakers have on the situation, it sure is now. The committee is still divided and has little idea where everything goes from here. The problem they have isn’t the momentum in the evidence, necessarily, it’s evidence of momentum or lack thereof.

The dots were more slightly more “dovish” in no small part because of the addition of Stephen Miran. While projections showed a few more rate cuts they also upgraded GDP, raised “inflation”, and left unemployment basically unchanged from prior forecasts (made in June). Why cut at all?

In light of the FOMC’s materials, the market took the rate cuts as perfunctory rather than any solid commitment on the part of befuddled officials. The phrase “every meeting is live” is a complete copout, an acknowledgement that if forced to make a decision on economic circumstances few of them would even try.

Data dependent doesn’t mean this.

Even so, the impact on the curves, while very modest, there was some movement in markets like forward rates. We’ve been following the steepening in term SOFR futures, to where the market was highly reluctant to price economic deterioration up at the front, pushing it out in time into late 2026 and the first half of 2027 (now the bottom of the inversion).

With the Fed at least appearing to be leaning toward some short run rate reductions, the market flipped that “twisting” in term SOFR futures with more (comparatively speaking) buying at the front and selling the bottom. The latter was likely in response to the upgraded GDP; not that the market believes GDP will be better, just that it raises the chances we have to go through another Fed pause process again at some point.

The main sticking point, other than perceived “sticky” CPIs, is purely momentum. As usual, there is some truth to this. Full-on recessionary downturns are as much about the weight of the setback as simply its appearance; the proverbial snowball sliding down the slippery slope. If that slope doesn’t appear to be slippery enough, or the snowball hasn’t acquired adequate mass, it won’t go much farther and everyone can breathe easier.

That is exactly how to read both the rate cut and all the rest including the dots. Sure, the labor market evidence points to trouble, but to the FOMC’s view, there isn’t yet proof of sufficient momentum behind it. Not yet – therefore, the rate cut.

We can see this in something like retail sales and their loose relationship with unemployment. Even though the correlation is almost non-existent, the parts which do stand out explain what I mean and what Jay Powell is thinking. Even Christopher Waller, apparently.

The decision

Foregoing the opportunity to forcefully counter the negative characterization of the labor market, the Federal Reserve’s policy body decided instead to rejoin the race to the bottom more halfheartedly than not. While the SEP, the Summary of Economic Projections, showed more of them expect more rate cuts compared to June, it’s not as if the group is committing to a full embrace of Pringles.

Everyone save Stephen Miran voted for the twenty-five, including Mr. Waller. Miran dissented and demanded a fifty, no surprise, while Waller softened his stance (as Mr. Van Metre predicted a few days ago). While not being privy to the full discussion, it does seem reasonably likely Chair Powell told Waller there was no way he could get the entire committee to give up on a spring and summer’s worth of inflation hysteria.

Again, consider the parallels to last year. The employment meaning unemployment situation is materially worse today than a year ago, and there is no argument on this (Powell admitted as much). Yet, last September officials set aside their “sticky inflation” narrative to vote for a fifty anyway.

But that also highlights one crucial difference, for Economists. They justified a fifty last year because policy rates were, everyone said, highly restrictive and far above neutral (the rate which is supposed to be neither restrictive nor accommodative; remember, this isn’t how the world works, but this is how Economists think and, as discussed yesterday, model everything). After last year’s cumulative 100-bps of reduction, the FOMC can justify to itself being much closer to neutral therefore less urgency to act even if the data is substantially weaker today.

The focus on the economy hasn’t shifted to the labor market, rather to labor market momentum (more on this below).

While there may not be overwhelming proof of the latter, there is more than enough to take it seriously therefore Mr. Powell was forced to take back “solid” and the dots reflected a modest decline relative to three months ago (the last time the SEP was put together) because of this.

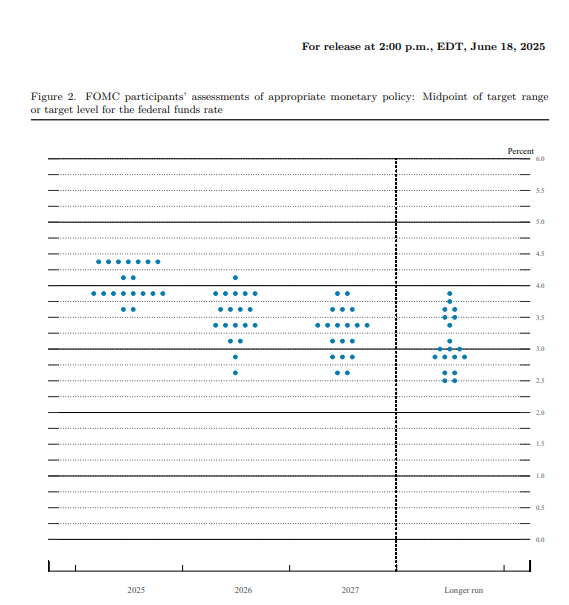

First off, Miran’s dots are massive outliers; the Fed’s newest Governor thinks the fed funds range should be heading below 3% by the end of this year. That’s going to skew projections compared with departed FOMC member Adriana Kugler (and we still have no word on what her departure was about).

On the other side of the divide, six of the 19 voting and non-voting members (governors and branch presidents) still believe the Fed is now done for the year and will pause from here on (the clique of irredeemable inflation-ists). That group is led by one other official who forecast a rate hike this year (Jamie Dimon?)

Two who saw only a single reduction for 2025 back in June now forecast two (with today being one of them). And nine believe there will be two more 25-bps drops from here through December. Even outside of Miran, there is some movement.

It took the median forecast down from 3.9% three months ago to 3.6%. For 2026, the median modestly relaxed from 3.6% to 3.4% - meaning the balance of the committee currently forecasts only a single additional rate cut next year after two more this year. It’s hardly much of a commitment.

Maybe more importantly, however gradual the Fed’s evolution, it is leading toward lower rates overall, inching closer to the long run position priced across the markets. Five of the FOMC now think the fed funds range will be below 3% by next year, with now eight forecasting the same for the long-term. That’s an increasingly significant change from a few years ago when higher-for-longer supposedly meant rates – and the neutral rate – would be far above where they and it had been prior to the supply shock.

All of that highlights not just a lack of consensus, almost polar opposite concerns. After all, they’ve got Miran (almost certainly) calling for five rate cuts while some unknown hawk believes there should be a hike over the next few months. With so many falling near the latter, there really was no way Waller would have swayed enough to a fifty without creating even more havoc with dissents (putting too many shoes on his other foot after Mr. Waller dissented back in July).

The upshot from the FOMC is that the committee is in complete disarray, lacking anything like a clear direction. Too many members can’t or simply refuse to let go of “inflation” of any kind, highly reminiscent of 2008 (in only this one respect) reflecting both that rotten institution’s deep-seeded inflation bias as well as fifty-plus years of getting inflation completely wrong and backward.

As noted in detail yesterday: if you have to be rebuked by Congress – TWICE - you are doing everything very wrong. Nothing has changed since.

Market reaction

I have been highlighting recently out how the SOFR curve (forward rates) has been pricing this latest bout of funding tightening and flat Beveridge confirmation. Few had been willing to stake much on near-term rate cuts because, well, everything just discussed in the section above. The unfortunate truth is that these bureaucrats have been handed the power to influence short-term rates, which means trying to predict a future path for them requires thinking irrationally without any clear anchor.

Data dependent nowadays means making it up entirely as they go. That’s not what it is supposed to mean – taking a position and then evaluating evidence either confirming or denying it. There is no position anywhere around Powell’s FOMC.

Guessing the FOMC’s short-term direction is like herding cats, a big reason why the shortest-term forward rate contracts simply price close to the Fed’s projections, therefore also why inversions start from the outer years and move up.

That is exactly the way the curve has been reshaping this summer, only in this case it wasn’t starting inversion just reigniting it from the back after last year’s force flattening for these same debates and reasons.

While studiously avoiding the near-term tenors like December 2025 and even March 2026, there has been pronounced buying out in the late 2026s and March plus June 2027s. The latter pair has been hammered home so much, March 2027 has become the new inversion bottom with June 2027 only a few bps (often a single basis point) behind.

Today, curiously enough, that all reversed. Not a huge amount, though noticeable. To begin with, the market “guessed” correctly that the Fed would chicken out and pull a twenty-five rather than go for fifty while being noncommittal on the bigger matters. Even the cash market was seeing more selling at the front (2s and 3s). For forward rates, the curve was modestly sold right from the start of the US trading (around 8:30am when New Yorkers finally arrive at their desks).

When the statement was released at 2pm along with the dots, there was a small “dovish” reaction. The 2-year yield slid to 3.46%, which would have been a new low, but it didn’t hold. In SOFR futures, contracts that were down five and six bps climbed back to even or slightly green only to turn around and get sold back to those earlier levels by the end.

All except December 2025 and January 2026. March 2026 ended up down by a single basis point.

For today, anyway, the market took the 2025 dots to mean a (very) loose commitment to the next limited series of rate cuts but nothing more beyond them, reversing the trading tendencies from this summer. Apparently, the statement, dots, and Powell’s performance was enough to at least get the Pringles can on the calendar for the remainder of the year – Jamie Dimon’s voter notwithstanding.

As for cash markets, the 2-year ended up at 3.52% (vs. 3.51% yesterday close) while the 10-year backed up to 4.06% (vs. 4.04%). Bills kept sliding, no surprise, since they still have to price a few more bps to complete the current rate cut plus the few more that do appear to be highly likely over the next few months.

Even so, the 6-month bill seems to be pausing itself right around 3.80% while the 3m is just getting to 4.00%. So, not much rate cut enthusiasm in the cash market among real money buyers like MMFers, either.

It is a perfect reflection of who and what is the greatest single source of uncertainty for financial markets, and that’s the institution Congress once mandated create stability in three main categories, employment, prices, and interest rates.

What (is) momentum?

Chair Powell was made a mockery immediately following the last FOMC meeting when he claimed the labor market was “solid”, only to see that idea obliterated by the Establishment Survey a mere two days afterward. It hasn’t gotten better since, with another payroll report coming in weaker still (August) at the same time another previous month (June) was revised to an outright negative.

The long-awaited QCEW not only confirmed the lack of solidity, it took that weakness several steps farther strongly implying job losses had begun to stack up from last year – as we know. The point is the labor evidence unlike inflation is everywhere and it is also unambiguous.

To his credit, Mr. Powell did address this flub at his press conference, stating in his prepared remarks, “Labor demand has softened, and the recent pace of job creation appears to be running below the break-even rate needed to hold the unemployment rate constant” before adding in response to a question, “I can no longer say [the labor market] is solid.”

THE LAST FOUR MONTHS LOOK LIKE MOMENTUM

While the FOMC Chair did his best to blame several other factors for the slowdown – citing “lower immigration and lower labor force participation” – the latter one is itself a response to that very weakness in employment (not the models treat it that way). However, he also acknowledged that job growth for whatever reason is too little to hold unemployment steady.

And that is why there was a rate cut today and probably a few more hereafter.

However, the reason the Fed refuses to commit to all that much is lack of evidence the clear weakness is becoming the self-reinforcing snowball; there isn’t any confirmation (or enough to satisfy econometric models) downside momentum is picking up and pushing unemployment beyond the point of return. From this view, a few additional rate cuts should offer enough support to solidify the economy before it goes too far.

While that may be their hope even their expectation, the FOMC is still hedging on its hedging here.

We can see this in their latest SEP projections. First, GDP was revised higher, with the central tendency (range) upgraded to 1.4% - 1.7% here in 2025 compared to 1.2% - 1.5% back in June. That’s still on the edge of annual recession territory, right in the window for stall speed. The unemployment rate forecast was left unchanged, almost certainly because of the rate cuts (again, in the models not reality).

All of this also explains the hawkish clique, too. Absent clear downside momentum, “only” some risk of it, the idea the economy is merely normalizing (not really weakening) remains somewhat plausible. In that case, any risk would be inflationary, be it tariff-driven (still no evidence for) or the regular “sticky” services sort.

Everything changes with that accelerating deterioration which would upend that solid economy and its potential inflation, putting it instead as a weak economy with a growing unemployment problem. The former is consistent with an insurance rate cut or two to ensure the economy remains solid so long as inflation doesn’t flash.

The latter, though, is where the FOMC would be into the fifties with little resistance even among the clique – like in 2008, they would simply shift their rate hike expectations out into the future.

An example of momentum can be seen from the relationship between retail sales and unemployment; starting with the fact there really isn’t one. Unemployment can be high and retail sales will be growing at what appears to be a solid rate (meaning recovery). The rate of unemployment itself doesn’t matter, the rate of change in the rate does.

Once at an inflection point – such as late 2000 or the middle of 2007 – the turn in unemployment which begins to speed up relatively quickly triggers a clear backlash in retail sales (as a proxy for the consumer economy overall) as it suddenly drops off. And it isn’t immediate, either. In past cycles, the quickening of the unemployment rate preceded the sharp in fall in retail sales by half a year and more.

In 2000, it was only a few months whereas in 2007 the difference was about half a year. In other words, once the tipping point for unemployment has been reached there is some time before that momentum trips up the entire economy having past the vicious cycle of full-on recession. By the time the data comes in showing that, however, it’s already too late.

That is why the hedging with a few rate cuts, what Waller has been arguing.

But, as you can see over the past few years, the unemployment rate hasn’t shot upward at all – the official rate, anyway. It has meandered higher, sure, but not gathering the kind of acceleration which is consistent with past recession cycle peaks. From this view, using the U-3 rate the economy may be losing steam but it hasn’t lost enough momentum to be a full-blown danger.

This data keeps alive the idea the economy isn’t weak, just normalizing after being red-hot a few years ago. Thus, the hawks.

On the other hand, if you do account for the labor force dropouts, which Powell himself dismissed, momentum looks quite different especially the past four months leading up to September. The labor force shrunk dramatically during them and employment either slowed to nearly zero (Establishment Survey before QCEW) or fell off quite sharply (HH Survey). In both cases, there is a very strong chance of what Powell said about there not being enough jobs to keep employment stable (somewhere Humphrey and Hawkins are very upset again).

If the adjusted unemployment rate more closely resembles the real economy therefore real momentum, then something like retail sales is already on the clock for a true peak. And that’s after having previously stumbled this year before picking up this summer mainly due to panicky consumers online shopping and automobile buying worried about price changes.

Once they stop tariff-distortion buying, where is momentum then? If it’s already lost, it is already too late to do anything about even assuming rate cuts would work.

The Fed refuses to offer any clarity because it has none to give. There isn’t enough evidence of downside momentum to satisfy econometric models, so officials can’t completely quash the present clique. At the same time, there is plenty of evidence momentum is a very real risk, therefore the clique has to go along with some hedging in the form of a single rate cut today and “live” meetings from here on to December.

And even that gives that group too much deference.

Officials are totally caught in between and the mess is creating unnecessary uncertainty. Not that it matters long run, because even after today’s fiasco of a debacle even sometinng like the dots are evolving closer to that market long run. The probability the Fed gets there keeps going up, being dragged kicking and screaming into that future.

For now, the FOMC is back into the Pringles can. As I’ve said here before, rate cutting cycles are incredibly difficult anyway and this one has several more frustrating components over and above the usual biases and econometric nonsense. Still, this is just nuts.

They always get there in the end, though the real power officials have is to make it as difficult as possible along the way. There were no hawks nor doves today, just headless chickens running all over with no purpose. Thanks again, Economics.